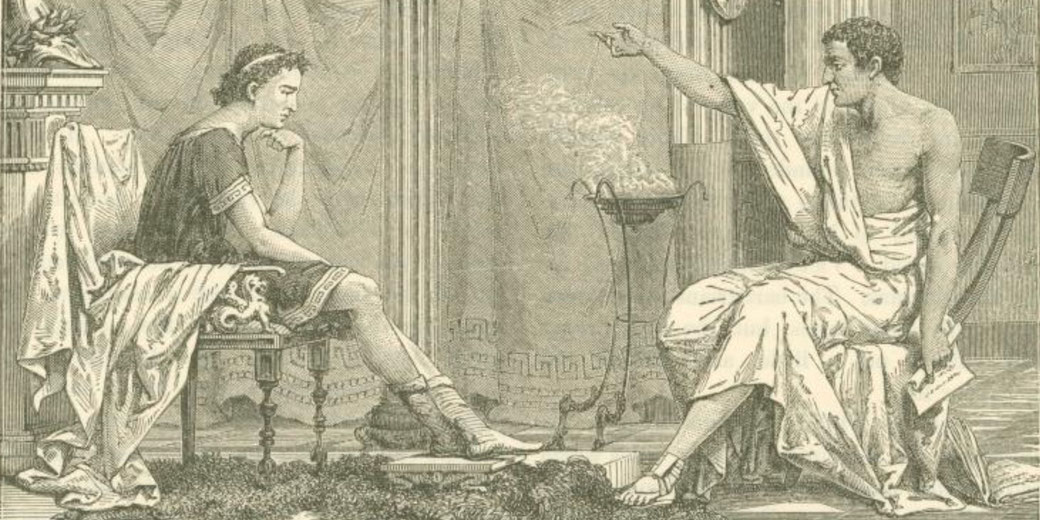

When Alexander was Aristotle's student: the greatest philosopher taught the greatest general

In 343 BCE, King Philip II of Macedon hired Aristotle to educate his thirteen-year-old son, Alexander. The philosopher and the prince spent several years together at Mieza, where Aristotle taught a range of subjects to prepare Alexander for kingship.

Their relationship left a powerful impact on Macedonian rule over the ancient world, as well as the spread of Greek thought.

The childhood of Alexander the Great

Alexander was born in 356 BCE in Pella, the royal capital of Macedon. His father, Philip II, had transformed the kingdom into the most powerful military state in Greece, while, his mother, Olympias, believed in her son’s divine ancestry and promoted his identification with heroic figures from myth.

From his earliest years, he is said to have developed a deep interest in Homeric poetry and admired Achilles as the ideal warrior prince.

At around the age of ten, he tamed the wild horse Bucephalus in front of his father, which apparently earned royal praise and marked him out as a trul exceptional individual.

Under the guidance of early tutors, he studied reading, music, poetry, and physical training.

He memorised epic verses, practised public speaking, and absorbed the heroic code that governed Greek values.

But, as he approached adolescence, Philip searched for a teacher who could prepare his son to lead a kingdom.

The philosophical phenomenon of Aristotle

Aristotle was born in 384 BCE in the coastal city of Stagira in northern Greece. His father, Nicomachus, was court physician to the king of Macedon and introduced his son to medical knowledge and royal custom.

When he became an orphan as a boy, Aristotle travelled to Athens, where he joined Plato’s Academy at the age of seventeen.

He remained there for twenty years, receiving an exceptional education in philosophy and science.

During his time at the Academy, he began to question some of Plato’s central teachings.

Instead of relying on abstract forms, he turned to nature and preferred detailed observation.

He believed that knowledge required explanation based on evidence, and he aimed to make a systematic list of the natural world.

After Plato’s death, Aristotle left Athens and moved to Assos in Asia Minor. There, he continued his research and advised local rulers.

Over time, his writings expanded to include ethics, biology, political theory, poetics, and logic.

At that stage of his career, no other philosopher in Greece could match the depth and variety of his work.

How Aristotle was convinced to travel to Macedonia

In the early 340s BCE, Philip invited Aristotle to return to Macedon. To secure his services, the king offered generous rewards and promised to rebuild Stagira, which had been destroyed during a previous campaign.

The proposal appealed to Aristotle, who accepted the role and was ready to teach the heir.

At a private estate in Mieza, Aristotle began teaching Alexander and a group of Macedonian young nobles such as Ptolemy and Hephaestion.

Some later traditions suggest that Cassander may also have received instruction from Aristotle, although his presence at Mieza remains uncertain.

Ptolemy would later rule Egypt and found the Ptolemaic dynasty, while Cassander became king of Macedon and Hephaestion remained Alexander's closest companion throughout his campaigns.

In that quiet setting, far from the distractions of the court, Aristotle delivered lessons beneath the colonnades and in shaded groves.

The estate was situated in the sanctuary of the Nymphs near Naousa, which offered a calm area with covered paths and gardens that encouraged study and thought.

What did Aristotle teach Alexander?

At Mieza, Aristotle introduced Alexander to logic, rhetoric, poetry, and ethics. He taught him to recognise fallacies, build persuasive arguments, and apply reason to human behaviour.

In addition to these subjects, he encouraged him to study astronomy, geography, zoology, and other natural sciences.

According to later accounts, Alexander excelled in memorisation, debate, and independent thinking.

During their lessons, Aristotle urged him to value restraint, seek justice, and avoid indulgence.

In matters of kingship, he advised that rulers earn loyalty through fair judgement rather than through fear or offerings of wealth.

In political theory, Aristotle praised moderation and insisted that reason should guide law.

Over time, Alexander made these teachings part of his approach and applied some of them in his dealings with conquered regions.

He preserved local traditions when it suited his aims, but promoted Greek learning wherever possible.

During his campaigns, he spoke with Indian thinkers, learned about Persian methods of rule, and gathered Babylonian records of astronomy.

These actions revealed the lasting imprint of Aristotle's instruction.

What happened to Aristotle?

After his time at Mieza, Aristotle returned to Athens in 335 BCE. There, he founded the Lyceum, a new school that welcomed students from across the Greek world.

In that institution, he lectured, wrote, and organised collections of books. His students, later called Peripatetics, followed him during his walks and engaged in detailed discussions on every branch of knowledge.

During Alexander’s eastern campaigns, Aristotle continued to receive specimens alongside detailed notes and official reports.

Alexander supported this work with funding and protection. As a result, the Lyceum became a learning centre that matched Plato’s Academy.

For more than a decade, Aristotle remained productive and influential.

After Alexander died in 323 BCE, anti-Macedonian feeling surged in Athens. A charge of impiety forced Aristotle to leave the city to avoid a trial.

He reportedly remarked that he would not allow the Athenians "to sin twice against philosophy," in reference to the fate of Socrates.

He relocated to Chalcis on Euboea and died there in 322 BCE. His writings survived in the form of lecture notes and private treatises, which his students preserved and copied.

Over 30 of his works remained influential for centuries.

How their time together shaped the ancient world

During his conquests, he carried Greek ideas eastward and introduced them to regions that had never encountered Hellenic learning before.

In each new city he founded, estimated at over twenty and many named Alexandria, he supported education, sponsored libraries, and encouraged scholarly exchange.

Scientific materials collected during his expeditions enriched Greek knowledge. At the same time, his decisions to mix local customs with Greek administration revealed the practical influence of his philosophical training.

In later centuries, Aristotle’s works continued to guide scholars in the Roman world, the Islamic world, and medieval Europe.

His ideas influenced figures such as Avicenna, Averroes, and Thomas Aquinas, and impacted the intellectual traditions of medieval universities.

Alexander’s campaigns made that influence possible, as they laid the foundations for the Hellenistic kingdoms that preserved and spread Greek learning.

Although their paths diverged after Mieza, the teacher’s ideas and the student’s actions shaped the direction of ancient civilisation.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.