How the First Triumvirate changed ancient Rome

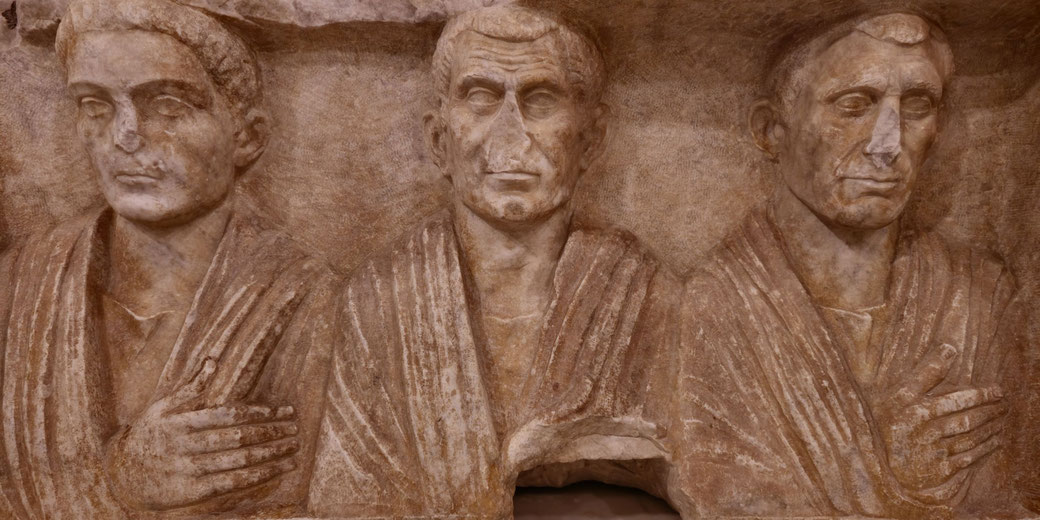

The First Triumvirate was a secret political alliance between three politicians during the late Roman Republic.

It was created in 60 BC by Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (known as Pompey 'the Great'), and Marcus Licinius Crassus.

This alliance was designed to allow these three individuals to control the entire Roman political system in order to help each other achieve their own, individual, aims.

Background: Rome in the 1st century BC

The Roman Republic in the 1st century BC was in trouble. Since the time of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC, the political system of the Roman Republic became increasingly under the power of wealthy and violent politicians.

The Senate had been split into two competing factions. On one side were the optimates, who were made up of the wealthy elites who were interested in maintaining the powerful traditional ruling class of Rome.

On the other side were the populares, who championed the causes of the common people.

However, when one of these factions gained dominance in political elections or gained a majority in the Senate, the other side would rely on powerful individuals who would resort to murder, violence, and even military invasions of the city of Rome itself, to swing the power balance back the other way.

In the 50 years before the First Triumvirate was formed, each side had enjoyed dominance in the Senate at different times.

The populares had seen influence under the general Marius, while the optimates had recently gained control of the Senate as a result of the reforms by the general Sulla.

However, by the beginning of 60 BC, two powerful Roman politicians seemed to be strongly on the side of the populares, and they were Pompey and Caesar.

The optimate majority were concerned that they were about to lose power again and actively worked to limit the influence that these two men had in Roman politics.

When Pompey and Caesar began to realise that they were being openly opposed by the Senate, they realised that unless they could find a solution to their problems, they would never be allowed to progress their political careers any further.

Pompey the Great's aims

In 60 BC, Pompey the Great was the most experienced and beloved military general alive.

Having risen to prominence during the time of the Social War and under Sulla's dictatorship, Pompey had rocketed to fame and power through a series of remarkable military achievements.

He had saved the city of Rome from the rebel consul Lepidus' revolt in 77 BC, defeated another rebel called Sertorius in the province of Spain in 73 BC, and had even helped crush the last elements of the Spartacus slave revolt in Italy in the same year.

He became consul in 70 BC, cleared the Mediterranean of pirates in 67 BC, and had defeated the long-time enemy of Rome, Mithridates VI of Pontus in 63 BC.

While on this campaign in Asian Minor, in the eastern Mediterranean, Pompey had even managed to absorb Judaea into the Roman republic's sphere of control.

So, when Pompey arrived back at Brundisium in Italy in 62 BC, he led an experienced army that was loyal to him alone.

The Senate wondered whether he would copy the example of Sulla when he had marched his army on Rome in 83 BC to seize power for himself.

Surprisingly though, Pompey dismissed his army and travelled to Rome as a private citizen, not as a conquering commander.

Once in the city, the Senate awarded him another triumph the third of his life, for his eastern campaigns.

However, as part of these celebrations, Pompey shared some of his new wealth with the common people by investing in new buildings and paid each of his loyal veteran soldiers 6000 sesterces (a Roman coin), which was worth over twelve years of wages.

Pompey's generosity made him even more popular with the people of Rome and made the Senate even more worried about his real motives.

Therefore, when Pompey approached the Senate to get their official approval for his decision made during the campaign against Mithridates and Judaea, the Senate was looking for any opportunity they could to limit his power.

The Senate pointed out that Pompey had acted beyond the original instructions given to him: he hadn't had any authority to capture new territories or create new provinces in the east, all of which Pompey had done.

What concerned Pompey the most was that he had promised his soldiers farmland when they retired.

However, since Pompey had technically acted outside of his authority, the Senate refused to grant these lands to Pompey's men.

As a result, Pompey now had thousands of disappointed and angry soldiers on the streets of Rome who had trusted him to fulfil his promise.

Consequently, Pompey had to find a solution to get the land he had promised to his men despite the fact that the Senate was hostile to the idea.

Crassus' aims

The second person who would make up the First Triumvirate was Marcus Lucinius Crassus.

In 60 BC, he was about 55 years and was the richest individual in Rome. While Crassus had had some military roles during his career, he spent most of his time in the business world, making a financial profit.

Crassus made a lot of wealth during the proscriptions of Sulla, where, it was rumoured, that he had put names of his personal enemies on the list of names, and then had them killed in order to seize their assets.

Using his sudden influx of wealth, Crassus then manipulated the sale of houses and buildings in Rome, forcing people to sell them for less than they were worth.

During this time, Crassus was able to form powerful connections with other Roman businessmen, from the equites class, who relied upon him for personal and business loans. Some of these men were tax-collectors.

They had gotten themselves in trouble by bidding too high on government tax contracts and they were suddenly unable to pay money back either to the Senate or to Crassus.

These men approached Crassus and asked for help. Crassus wanted his money back and refused to free them from their debts to him.

However, as long as the Senate also refused to let them get out of their tax contracts, these men would never be able to pay Crassus either.

As a result, Crassus approached the Senate to ask for the tax contracts to be reduced.

Just as the Senate was worried about Pompey's popularity, it was also worried about Crassus economic power.

And, just as they actively opposed Pompey, they also opposed Crassus and refused to honour his request.

So, in 60 BC, Crassus was looking for some way to get around the Senate's refusal to cooperate.

He ideally wanted someone in the Senate who would support his request: someone with enough power and influence to overturn their hostility to him.

Julius Caesar's aims

In 60 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar was the youngest of the three men, at about 40 years old. He had just returned to Rome from a successful military campaign in Spain.

Caesar had achieved the requirements to celebrate his first triumph. However, he was also seeking to be elected as one of the consuls for the next year 59 BC.

The Senate, who was worried that he was another populares politician who could cause them concern gave him an ultimatum: either have a triumph or stand for election.

This was an unfair demand, but the Senate assumed that Caesar would take the triumph, as Romans went their entire careers in the hope of getting just one triumph.

However, Caesar shocked the Senate by giving up the triumph and choosing to contest the consular election instead.

However, Caesar knew that his chances of becoming consul were small because he did not have the same level of popular with the people of Rome as other potential candidates.

Caesar needed to work hard to convince the citizens to vote for him. In Roman political terms, this usually required a lot of bribery: offering monetary incentives for people to vote for him over his rivals.

While bribery is considered a form of corruption in modern political terms, it was entirely acceptable in ancient Rome.

In fact, most people seeking election in Rome often went into significant debt to be elected, knowing that by gaining a position could mean making enough money to pay back their debts.

Caesar himself did not have enough money to pay the amount required to bribe enough voters.

In order to raise the funds necessary, he had to find a financial supporter. Before he had begun his previous campaign in Spain, Caesar had relied upon a loan from Crassus, so it was natural that he might turn to him again in this instance.

How was the alliance formed?

Each of the three men faced unsurmountable challenges that could not be resolved alone.

Their difficulties were public knowledge and there was significant tension in Rome about what would happen.

However, it was Julius Caesar who realised that the three men could actually use their individual strengths to help each other out.

In 60 BC, Caesar invited Crassus and Pompey to a secret meeting. Since this discussion was secret, the exact details of what was decided is unknown.

However, based upon what would happen over the next two years, historians can confidently identify the terms of their agreement.

Caesar promised that, if he became consul, he would ensure that legislation would be enacted that would solve both Crassus' and Pompey's problems.

In return, he needed Crassus' money to pay for votes and Pompey's soldiers to intimidate voters on the day to ensure Caesar won.

The most difficult part of this agreement was the fact that Pompey and Crassus hated each other.

Ever since Pompey had unfairly stolen Crassus' triumph at the end of the Spartacus revolt, the two men had been direct opponents.

However, Caesar was able to encourage the two to overlook their personal animosities in order to work together.

Once the agreement had been reached, the three men knew that what they were doing was considered highly illegal in Roman politics and the three men swore to keep their arrangement secret for as long as they could.

Caesar's consulship

The First Triumvirate was successful in achieving their goals. The first order of business for the First Triumvirate was to get Caesar elected as consul.

This was accomplished by bribing the voters and using Pompey's military strength to intimidate anyone who opposed their candidate.

Caesar was successfully elected as consul for 59 BC, and he used his position as consul to pass a series of laws that increased his own power and weakened the Senate.

As promised, Caesar passed laws that gave him some public land to Pompey's veterans and arranged tax breaks for Crassus' wealthy friends.

The secret agreement had been a success and the three men were able to control Roman politics for an entire year.

However, people began to work out what had happened, and the Senate became suspicious.

The end of Caesar's consulship

When Senators began calling for the three men to be held accountable for illegally manipulating Roman politics, Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus had to find some solutions.

Caesar used his position as consul to pass the Lex Vatinia, a law that gave him command of Rome's armies in Gaul.

This meant that he would be away from Rome for five years, which suited Pompey and Crassus just fine.

They did not want Caesar around while they worked on consolidating their power. It also meant that Caesar could not face legal proceedings for illegal actions during his consulship. He was immune from this until his military command expired.

Crassus and Pompey continued to use their political power and money to put their allies in the consulships for the next year, on the understanding that they would also be kept safe from any legal charges.

Things begin to unravel

Pompey and Crassus had different visions for Rome's future, and they soon began to clash.

Pompey wanted to maintain the status quo, while Crassus wanted to increase his own power.

This led to tension between the two men, which was made worse by Caesar's continued absence.

Caesar had spent the years away in Gaul, conquests which had made him even richer and more powerful.

By 54 BC, he quickly realized that Pompey and Crassus were no longer allies but had returned to their old rivalries.

To restore the power of the alliance, the three men met again in 56 BC, at the down of Luca, and renewed their political arrangement.

This time, Caesar was promised an extra five-year command in Gaul to keep him safe from being charged for his activities in 59 BC.

Pompey and Crassus wanted military commands over different provinces. Pompey got Spain and Crassus got the east, which put him in a position to win military glory against the Parthians.

Once the new deal had been finalised, the three men went their separate ways: Caesar back to Gaul, Pompey to Rome and Crassus to the east.

In May of 53 BC, Crassus was defeated at the Battle of Carrhae while leading Roman forces against the Parthians.

It was said that the Parthian king had Crassus killed by pouring molten-hot gold into his mouth as a way of punishing him for his immense greed.

This left Pompey and Caesar as the only members of the First Triumvirate still alive.

Pompey began switching his political allegiance to the optimates faction and began openly opposing Caesar's actions in Gaul.

When Caesar's final command began to expire at the end of 50 BC, the Senate warned him that he was going to be dragged before the court.

Caesar reached out to Pompey for further help but was rejected.

Realising that he was running out of options, Caesar knew that he either accepted his fate at the hands of the Roman legal system and the optimates that controlled it or choose a more drastic action.

Feeling like he had no other option, in January of 49 BC, Caesar marched his armies across the Rubicon River from Gaul and into Italy with the declared aim of capturing Rome and expelling the optimates.

This was an act of war against Rome itself, and it meant that Caesar would have to fight Pompey and his allies to seize control.

The Civil War between Caesar and Pompey lasted for just two years and Caesar emerged victorious.

He would go on to become dictator of Rome and change Roman politics forever.

What were the implication of the First Triumvirate?

Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar were three very different men who came together to achieve their own goals.

They were successful in controlling Roman politics for a time, but their different visions for Rome's future led to tension and eventually conflict.

What made the First Triumvirate so important is that it showed that just three people had the ability to control the entire Roman political system.

Once Rome realised this, it would then be copied again later by three more men: Octavian, Lepidus, and Mark Antony.

Their alliance would be dubbed the Second Triumvirate and it would finally destroy the Roman republic forever.

As a result, it could be argued that the First Triumvirate was indirectly responsible for destroying republican Rome.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.