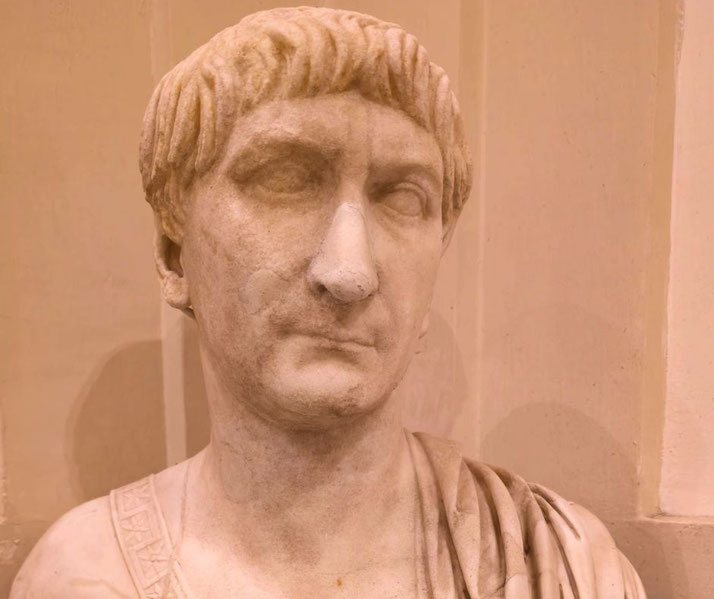

Gaius Marius and the origin of the Roman legions

Gaius Marius was one of the most influential and significant figures in Roman history, as he transformed the Roman Republic through his military reforms.

As an outsider to the Roman aristocracy, Marius's rise to power was both remarkable and he became one of the most decisive leaders, becoming consul an unprecedented seven times.

Ultimately, Marius paved the way for future military leaders thanks to his professionalization of the Roman army, which became a cornerstone of Rome's imperial strength.

How Marius entered Roman politics

Gaius Marius was born near Arpinum, a small town in Latium, in 157 BC. His father was a landowner of modest means, and his mother came from a wealthy family.

Gaius' family was probably of equestrian status, which meant that they were wealthy aristocrats and were probably well known in the area.

When he was seventeen years old, Marius’ father died, and he inherited the family estate.

While he may have been influential in his hometown, Marius was unknown in Rome and when he sought to begin a career in Roman politics, he was considered a novus homo, which means 'new man'.

This meant that he was the first member of his family to serve in the Roman Senate.

Marius married into the wealthy Julii family, which helped him advance his political career.

Marius' first positions of influence

In 134 BC, Marius served as a military officer at Numantia in Spain under the famous general Scipio Aemilianus.

This posting gave him valuable military experience and was the first step in establishing a name for himself, particularly at the siege of Numantia.

It would take a few years, and several failed attempts at election to different political positions in Rome before he had a sufficient reputation to enter the political arena.

To help in his career advancement, Marius formed a powerful political alliance with the influential Metelli family, who provided him with the extra money and important social connections he needed to advance his career further.

Finally, Marius was elected to the position of Tribune of the Plebs for the year 119 BC.

This was the beginning of a rapid series of political appoints for Marius. While he failed to be elected to the position of aedile in 117 BC, he was successful in becoming a praetor in 115 BC.

Then, in 114 BC, Marius became propraetor in the lucrative province of hispania ulterior in Spain.

When Marius returned to Rome in 113 BC, he had accumulated a significant amount of wealth and respect.

The Jugurthine War begins

During the period of time where Marius was rising through the political ranks, Rome was facing a crisis in its northern African provinces.

In 118 BC, Micipsa, the king of one of Rome's allied kingdoms, called Numidia, had died.

The kingdom was inherited by his two sons, called Hiempsal and Adherbal.

However, their adopted brother, named Jugurtha, challenged them for the throne. Jugurtha, had Hiempsal killed and then attacked Adherbal.

As an ally of Rome, Adherbal had sought Roman military aid in the war with his Jugurtha.

Instead of sending the soldiers that Adherbal requested, in around 116 BC, the Senate ordered the two men to divide Numidia into two separate kingdoms: each ruled by one of the claimants to the throne.

While Jugurtha and Adherbal initially obeyed these orders, in 113 BC, Jugurtha decided to take matters into his own hands and invaded his brother’s kingdom.

The Roman Senate did not immediately respond with military force. Instead, they sent a number of delegations to Jugurtha to try and resolve the situation.

However, in the meantime, Jugurtha besieged Adherbal in his capital city of Cirta.

When the city fell in 112 BC, not only was Adherbal captured and executed, but a large number of Roman traders were massacred as well.

This event shocked the Roman world and the Senate finally declared war on Jugurtha in 111 BC.

The Roman armies had little success in the first few years of the war, since Numidian forces, which were predominantly composed of cavalry, often avoided pitched battles with the Roman infantry armies.

So, in 109 BC, one of the Metelli family, Quintus Caecilius Metellus, was elected as consul and was sent to Numidia to take control of the campaign.

One of the military legates that Metellus took with him to Numidia was Marius.

During his year in command, Metellus had little more success against Jugurtha than the military commanders before him.

By the end of the year, Marius believed that he could turn the tables on the Numidian king, but needed to be elected as consul to do so.

When Marius informed Metellus that he wanted to be released from his military duties in order to return to Rome to stand for the consular elections, Metellus refused to give him permission.

Metellus believed that Marius was being far too ambitious for a novus homo.

However, Marius was not dissuaded and, in direct defiance of the commander, Marius left the military camp and sailed back to Rome.

Marius' dramatic military reforms

Much to Metellus' surprise and frustration, Marius was successful in becoming one of the two consuls for the year 107 BC.

By this stage, Marius was popular with the people, and the Assembly voted for Marius to take command of the Jugurthine War instead of Metellus.

Marius had encouraged them in this decision by boasting that his experience in north Africa had given him an insight in how the war could finally be won.

Before he sailed to Numidia to take charge, Marius needed to raise an army.

However, the issue of landless citizens, which Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus had tried to fix remained an ongoing problem in the recruitment process.

Marius could not find enough soldiers to create the forces he needed.

So, Marius devised a practical solution. Rather than requiring soldiers to own their own land, Marius asked for volunteers, regardless of their level of wealth.

He offered to pay these volunteers while they were on campaign. This had never been done before.

Prior to this, soldiers were responsible for their own upkeep.

The brilliance of Marius' change to recruitment is that many more people came forward to serve in his army.

The attraction of receiving regular pay was made more enticing by the fact that Marius also promised to give each soldier their own land when they completed their military service.

This new scheme was very successful. Marius quickly raised an army and headed to north Africa to begin his campaign against Jugurtha.

Winning the Jugurthine War

The campaign against Jugurtha was a difficult one, and it lasted for several years.

While Marius was able to achieve victory in a number of battles, Marius spent most of his time trying to convince Jugurtha’s allies to switch sides.

Finally, with the number of supporters running out, Jugurtha fled to the safety of the neighbouring kingdom of Mauretania, which was controlled by his father-in-law, King Bocchus.

Since he was hiding in a land that was not at war with Rome, Jugurtha was safely out of Rome's reach, which meant that the war could not be resolved.

However, Marius did eventually end the war, but not in the way he wanted. It was one of Marius' subordinates, called Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who finally brought an end to the war.

Sulla had persuaded Bocchus to capture Jugurtha and hand him over to Marius, which he did.

With Jugurtha in chains, the war was declared over in 105 BC.

Although it was Sulla’s personal intervention that led to the capture of Jugurtha, since Marius was the overall commander, Marius was the one that was given the triumph in Rome in 104 BC.

At the culmination of the triumphal parade, the Numidian king was executed.

Having finally won the long and difficult Jugurthine War, Marius became a military legend among the people of Rome and Marius frequently boasted of his achievements.

However, Sulla remained resentful towards Marius for not giving him credit for the capture of Jugurtha.

The war against the Cimbri and Teutones

While the Jugurthine War was happening, Rome faced another military crisis: this time in the north of Italy.

In 113 BC, two Germanic tribes, called the Cimbri and the Teutones (with their allies, the Ambrones), appeared at the east of the Alps.

These two groups were marching south, and Roman armies were sent to engage them.

However, in 105 BC, these armies were defeated suffered a catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Arausio, and the Romans began to panic, fearing a conquest of Italy by foreign invaders.

Marius’s popularity increased even further when he was elected as consul for the second time for 104 BC and was given the command of the Roman forces against the Cimbri and Teutones.

This campaign was a long one and required a long-term military strategy. As a result, Marius was elected to the consulship for 103, 102 and 101 BC: something that had never been achieved in Roman politics before, let alone for a novus homo.

Finally, in 102 BC, Marius defeated the Teutones and the Ambrones in a great battle near Aquae Sextiae (modern-day Aix-en-Provence, France).

Then, in the following year, in 101 BC, he defeated the Cimbri in a similarly decisive battle near Vercellae (modern-day Vercelli, Italy).

How effective was Marius as a politician?

Marius’s various military successes made him a popular figure among the people, and he used this popularity to further his political career.

In 100 BC, he was elected consul for the sixth time. He then ran for the office of censor for 97 BC, but he was defeated by his rival Lucius Appuleius Saturninus.

It was around this time that Marius' reputation began to suffer setbacks. He had been a popular military hero, but when he focused on political life in Rome, he found that he was less able to defeat his political opponents.

He had initial success by convincing the Senate to provide the promised land to his retiring soldiers from the Jugurthine War.

These veterans were granted farms in Africa. However, Marius failed to achieve the same for his veterans from war against the Cimbri and Teutones.

The Senate argued that no new land had been conquered, so there was no land to reward them with.

In desperation, Marius asked the Assembly for land but also failed. In an attempt to force his proposal through, Marius’ soldiers used physically force on voting day, which finally resulted in Marius' request being accepted.

However, the use of violence in the voting process outraged many Romans and Marius was criticised for manipulating the political process for his own personal desires.

Realising that Marius was making too many enemies in the Senate, he knew that he was no longer safe in Rome.

He claimed to have a commitment to honour in the east of the Mediterranean and left Rome for several years. In his absence, Rome faced a significant crisis with its Italian allies.

Marius' role in the Social War

In 91 BC, a group of Italian allies known as the socii rebelled against Rome in what was called the Social War.

The rebels were fighting for the right to Roman citizenship. The rebellion quickly spread, and much of Italy was soon in open revolt against Rome.

The conflict raged for over two years, with military victories on both sides. The Roman republic was at genuine risk of collapsing, and the Senate called on all of their resources to save the city from collapse.

Putting their previous concerns aside, they called on the greatest military hero in Roman history to help lead their armies. Marius had already returned to Italy from the east.

As a result, Marius accepted the call for help and took command of the Roman armies again.

Along with the other Roman commanders, including his previous sub-ordinate Sulla, Marius successfully fought off the rebels and restored order to Italy.

The conflict between Marius and Sulla

Marius’s career began to decline in 88 BC when he clashed with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Sulla had been given command of the Roman forces against Mithridates VI, the king of Pontus (in modern-day Turkey).

However, Marius claimed that he should have been given the command instead, and used the Assembly to strip Sulla of the honour and took the military role instead.

In anger, Sulla raised an army and marched on Rome to both punish Marius and take back the command. Marius fled the city for safety.

When Sulla was confident of his control of Rome, he retook the command and marched his army east to fight Mithridates.

However, while Sulla was gone, Marius and his supporters retook Rome and officially declared Sulla an 'enemy of the state'.

When Sulla heard about this turn of events, he responded by marching back to Rome in 83 BC, but when he arrived, he was told that Marius had passed away in 86 BC.

By the time of his death in 86 BC, Marius had been elected consul seven times.

This made him the first person in Roman history to achieve seven consulships. He held the office of consul in 107, 104, 103, 102, 101, 100, 86 BC.

Why was Gaius Marius significant to Roman history?

Marius' impact on Roman political life and military structures was significant. He helped to cement the concept of the career politician and also reformed the structure of the Roman army.

His military successes increased Rome's territory and made him a popular figure among the people.

However, his political enemies eventually brought about his downfall. He is remembered as one of Rome's most significant historical figures.

Ultimately, it would be Marius’ creation of a professional army of volunteer soldiers that would have the longest impact on the Roman world.

This was the first step in the creation of a permanent army, which would eventually evolve into the legions of the Roman Empire.

However, this meant that soldiers became loyal to their general rather than to the Republic itself.

As a result, generals that provided money and farmland upon retirement used these enticements to recruit men who would do whatever they wished, even if this meant attacking Rome itself.

Marius’s military accomplishments earned him a place among the great military commanders in history.

In addition, his reforms to the Roman army were influential and had a lasting impact on subsequent generations of Roman soldiers.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.