The power and wealth of Middle Kingdom Egypt

The Middle Kingdom of ancient Egypt, which lasted from around 2040 to 1782 BC, was a time of significant prosperity and military expansion for the pharaohs.

Also, it is often considered to be the literary 'golden age', as the hieroglyphic writing system became more sophisticated.

In particular, literature flourished during this time, and the form of hieroglyphs that developed during the Middle Kingdom became the standard for much of Egyptian history, even into the New Kingdom.

This success was attributed to kings who ruled the land with a strong hand and, as a result, the country experienced an influx of wealth through trade relations with distant nations.

However, as powerful as Egypt was at this time, its collapse would happen remarkably quickly.

End of the First Intermediate Period

Before the beginning of the Middle Kingdom, Egypt was engulfed in the chaotic and violent First Intermediate Period.

Following the fall of the Old Kingdom, the land had been torn apart by continuous wars between various regional lords who all sought to conquer the kingdom for themselves.

However, it wouldn't be until the rise of Mentuhotep II (who ruled from c. 2060-09 BC), part way through the 11th Dynasty that this period of destruction ended.

Mentuhotep II was a great warrior-king who lived in southern Egypt and was in direct competition with the pharaohs of the 10th dynasty who lived in the north, in the city of Herakleopolis.

After the 10th Dynasty kings desecrated the sacred necropolis of Abydos during Mentuhotep's 14th year in power, he sent his armies north to Lower Egypt to defeat them.

It would be a drawn-out war, which would only be completed shortly before his 39th year, when he changed his royal name to 'Shemataway', which meant 'He who unifies the two lands'.

This victory finally re-united the two halves of the country, which then resulted in political and economic stability which hadn't existed since the end of the Old Kingdom.

The Middle Kingdom had now begun.

One of the most important changes made during Mentuhotep's reign was the establishment of Thebes as the new capital city of his kingdom.

This site did not appear to have been a significant location prior to this point.

However, by elevating Thebes' importance in this way would have consequences for centuries afterwards.

Following his reunification, Mentuhotep II led a number of military campaigns during his reign, particularly into the north-west Sinai region and to Nubia in the south.

He even built a military fort in the region of Elephantine to maintain control in the south.

Mentuhotep II would rule for 51 years, during which he built a great mortuary temple at the West Bank at Deir el-Bahri near Thebes in preparation for his death.

Attached to it was a multilevel terraced tomb with covered walkways. It was an ambitious building project and is said to be the inspiration for Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple, which was built hundreds of years later.

After his death, Mentuhotep II was succeeded by his son, Mentuhotep III, who continued with many of his father’s policies.

He strengthened the country's borders and had an interest in architectural building.

He also expanded Egypt’s trade routes. He was then succeeded by Mentuhotep IV, but little is known about his reign.

The problem of the Nomarchs

During the First Intermediate Period, regional warlords, known as 'nomarchs' had held much of the power in Egypt, and they fought each other to expand their control.

Each nomarch was the commander in a designated region of Egypt, called 'nomes'.

However, when a single pharaoh managed to unify the kingdom once more, he had to reestablish a clear hierarchy.

Even though the pharaoh was the absolute ruler of ancient Egypt, since he was considered to be a god on earth, the king could not be in all places at once.

Therefore, he needed the nomarchs to act on his behalf, as long as they promised to be loyal to him.

As a result, the king appointed individual nomarchs as the governors of his nomes, to ensure that the royal rulings were being enforced throughout the provinces of Egypt.

These nomarchs still held great power and were responsible for collecting taxes, maintaining order, and leading the military in times of war.

Even though the Middle Kingdom pharaohs worked to control the nomarchs and avoid challengers to the throne, over time, the nomarchs became very powerful.

They often acted independently of the king and even engaged in military campaigns without his permission.

This led to a lot of conflict between the king and the nomarchs.

The series of powerful pharaohs of the 12th Dynasty

Amenemhat I, who had been a vizier under the previous pharaoh, established the 12th Dynasty and moved the capital from Thebes to a new city, Itj-tawy, south of Memphis.

His family line would rule for the next 200 years. Some scholars believe that the Middle Kingdom only truly began with his dynasty due to the length of his reign and the impact on culture Amenemhat I had.

Amenemhat I ordered many miliary campaigns and built fortresses, to try to counter invasions from neighbouring countries.

He restored a number of religious monuments and built a pyramid for himself, but this was smaller than the great pyramids of the Old Kingdom.

His pyramid was made mostly of blocks of limestone and mudbricks, but did include some granite blocks from other Old Kingdom pyramids.

Some mystery surrounds the death of Amenemhat I. Some evidence suggests that he might have been assassinated.

If so, this may indicate there was political unrest at the court towards the end of his reign.

Regardless of the cause of his death, Amenemhat I was succeeded by Senusret I.

Senusret I initiated many grand buildings. He built monuments to gods and erected two red granite obelisks in Heliopolis to celebrate his 30-year jubilee.

One of these is still standing today and is the oldest in Egypt. He continued Egypt’s aggressive expansionist tactics in Nubia and ensured the military remained under his control, rather than the local rulers.

Senusret I was then succeeded by his son, Amenemhat II, who reigned from about 1929 to 1895 BC and continued his father's policies of stability and prosperity.

The most famous monument from his reign is the White Pyramid at Dahshur, which was originally clad in shining limestone.

Amenemhat II was succeeded by his son, Senusret II. He is known for his diplomacy and keeping the balance of power between the nomarchs and his government.

He had an interest in agriculture and established a whole new irrigation system in the Faiyum region.

He built dams and dug canals to create more land for cultivation.

Senusret III: The greatest king of the Middle Kingdom

After the death of Senusret II, his son, Senusret III took the throne. His reign lasted from approximately 1878 to 1839 BC and was a time of the greatest prosperity and growth for Egypt of this period.

Senusret III was a successful and powerful ruler, who spent a lot of time focusing on military successes.

He led a particularly violent invasion of Nubia, where he enforced his control over the region by constructing of a series of forts along the Nile, including the fortress at Semna, to secure Egypt's southern border.

He also led expeditions into Palestine and Syria, primarily to increase trade connections, which continued to enhance the prosperity of Egypt.

To achieve all of these things, he had become an effective administrator, who worked to simplify and reorganise out-dated traditions.

For example, Senusret III divided Egypt into three large districts and appointed councils to govern them.

This led to the further weakening of the power and role of nomarchs, enabling the central government to have greater control of distant regional areas.

Senusret III was a typical warrior-king, whose successful military campaigns gained him popularity and admiration from his people.

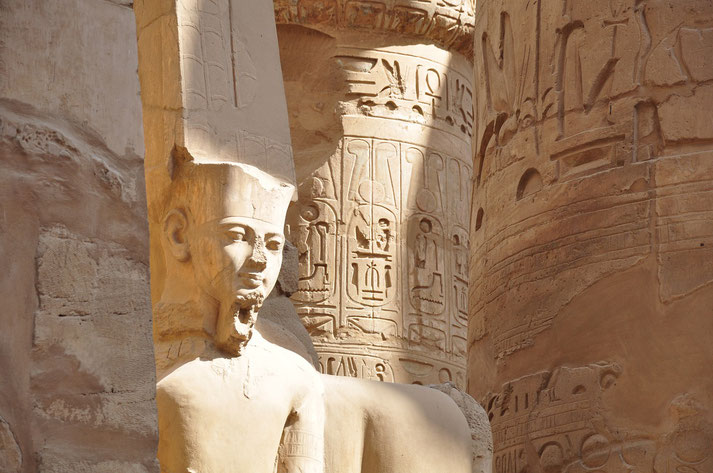

His impact was not just military however: he also built many temples and monuments, as well as making improvements to a number of existing ones including the Temple of Amun at Karnak.

He also has his own pyramid built at Dahshur, which was largest of the 12th Dynasty, which stood at approximately 78m high.

During this time, Egyptian literature, art and architecture reached new heights. Several famous texts still survive from this time.

One of the most famous of them were the Execration Texts. These are spells written on pottery and statuettes which were then broken and buried as a way of cursing one’s enemies.

In addition, a number of literary works, including the 'Tale of Sinuhe' became very popular.

Amenemhat III

Amenemhat III succeeded his father Senusret III. Egypt continued to experience economic prosperity under his leadership, which lasted from around 1860 to 1814 BC.

He established mines around Sinai, Tura, and Nubia, among others, exploiting precious resources such as turquoise and copper regularly during his 45-year reign.

He continued with the trend of impressive building projects including fortresses, temples and other religious buildings across Egypt.

He also started building a pyramid for himself at Dahshur, now known as the Black Pyramid thanks to the exposed, decayed mudbricks at its core.

Unfortunately, the pyramid was built on unstable ground, and it was damaged by flooding, so it was abandoned.

As a replacement, Amenemhat III built a second pyramid at Hawara and was eventually buried there.

End of the 12th Dynasty

Amenemhat III was succeeded by Amenemhat IV. However, compared to his father, he had a relatively short reign but did not have a male heir.

As a result, the rule passed to his sister (or some say wife), Sobekneferu, also called Nefrusobek.

She may have been the first woman to rule Egypt, and, after a short four-year reign, the 12th Dynasty ended in 1802 BC with Sobekneferu, as there were no further heirs.

13th Dynasty

The 12th Dynasty was known for its strength and prosperity, however the 13th Dynasty that followed it was not as strong.

While they inherited the wealth from the previous dynasty, a series of weaker leaders and very short reigns led to destabilisation.

This meant that there was less cases where succession passed directly from father to son.

Instead, the title of king seeming to circulate between different powerful families.

As a result, there were over 50 rulers between approximately 1803 and 1640 BC.

End of the Middle Kingdom

By the end of the 13th Dynasty, Egypt fell into chaos again. This led to a decline in the centralised control of the kingdom, and the borders of the Egyptian territories slowly collapsed.

As a consequence, The Middle Kingdom came to an end, since there was no longer a single ruler who controlled the entire land.

The long-term enemies of the pharaoh, like the Nubians to the south, took advantage of the situation to launch their own campaigns to recapture lands that had previously been seized by the Egyptians.

Just like the end of the Old Kingdom, the collapse of the Middle Kingdom led to another period of chaos and civil war known as the Second Intermediate Period.

Second Intermediate Period

During the Second Intermediate Period, Egypt was invaded by a people group called the Hyksos around 1650 BC.

They were from the Levant and introduced new technologies such as the horse-drawn chariot and advanced composite bows to Egypt.

The Hyksos would hold power over the northern delta region of Egypt for around one hundred years.

Their cultural influence on the region would be adopted by future Egyptians, but during the Second Intermediate Period, they were considered to be invaders and the primary threat to the re-establishment of a new Egyptian kingdom.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.