What clothes did people wear in ancient Greece?

The fashion of ancient Greece, characterized by its flowing drapery and elegant simplicity, created garments that could be both practical and symbolic.

The Greeks demonstrated a unique flair for combining form with function, an approach that has influenced Western fashion for centuries.

But what were the secrets behind the spinning and weaving of their iconic textiles?

How did the length of a chiton or the color of a himation speak volumes about one's place in society?

And how did patterns, colors, and decorations not only beautify but also communicate status, gender, and identity?

What materials were ancient Greek clothes made from?

The choice of materials for ancient Greek clothing was largely dictated by the local environment and the resources that were readily available.

Linen, made from the flax plant, and wool, sheared from sheep, were the primary fibers used to create the garments that have become synonymous with Greek fashion.

Linen, with its cool and lightweight properties, was particularly favored during the warm Mediterranean summers.

Wool, on the other hand, provided warmth in the cooler months and was versatile enough to be spun into various grades of thickness and softness.

The process of transforming these raw materials into wearable textiles was a labor-intensive one that reflected the skill and craftsmanship of ancient Greek society.

Flax stalks were harvested and subjected to retting, a process that loosened the fibers from the stem.

These fibers were then separated, spun into threads, and woven into linen cloth on looms.

Wool underwent a similar transformation, being carded to align the fibers before spinning.

The woven wool was often fulled, a cleansing process that also made the material denser and softer to the touch.

The actual fabrication of clothing was a domestic task, typically undertaken by women of the household.

Minimal cutting was needed, as the rectangular pieces of fabric were draped and fastened to the body in ways that allowed for both freedom of movement and modesty.

The most common clothes ancient Greeks wore

The foundation of ancient Greek clothing was composed of a few essential garments, designed with an emphasis on both function and form.

The chiton, a versatile tunic worn by both men and women, was a staple of the Greek wardrobe.

For men, it typically fell to the knees, while women's chitons reached their ankles.

This garment was created by draping a rectangular piece of cloth around the body and fastening it at the shoulders with pins or brooches, then belting it at the waist.

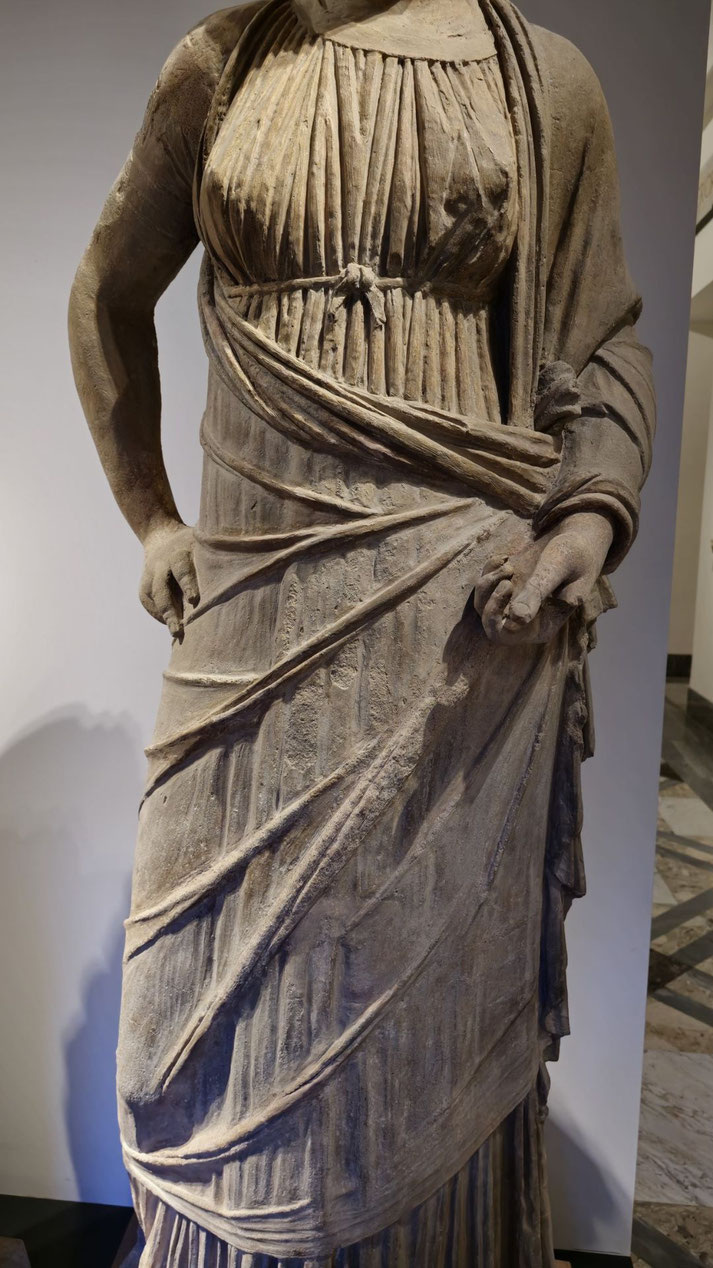

The peplos, a garment exclusive to women, was similar to the chiton but was made from a heavier fabric.

It was folded over at the top before being wrapped around the body, creating a flap known as an apoptygma, and then girdled at the waist, giving the illusion of a double-layered garment.

The apoptygma could be adjusted to reflect personal style or practicality and often bore intricate patterns or embroidery.

The himation, a cloak that could be worn over the chiton or on its own, was another key element of Greek attire.

This large rectangular piece of fabric was typically draped over the left shoulder and wrapped around the body in a manner that allowed the right arm to remain free, facilitating movement.

The himation could be adjusted for warmth, modesty, or style, and was worn by all segments of society, its fabric and drape often signaling the wearer's status.

For outerwear, the Greeks developed the chlamys, a shorter cloak fastened at the right shoulder and worn by men, especially soldiers and young men, for added mobility and ease of access to a sword belt.

It was practical for travel and horseback riding, and its military association made it a symbol of the valorous and the virile.

How clothing changed for rich and poor

In ancient Greek society, clothing was a clear indicator of an individual's social status and wealth.

The quality of the materials used, the complexity of the garment's design, and the presence of dyes or decorative elements could all signify the wearer's position within the social hierarchy.

Wealthier Greeks could afford finer fabrics, such as softer, thinner wool or imported linen, which were more comfortable and visually appealing.

They also had access to brightly colored dyes, which were often expensive and labor-intensive to produce, especially the coveted purple dye extracted from the murex snail. Thousands of murex snails were required just to dye one garment.

By the Hellenistic period, imported fabrics such as cotton from India and silk from China became prized possessions of wealthy Greeks.

The length and elaborateness of a garment further communicated social standing.

For example, a longer chiton was typically associated with the leisure class, who did not engage in manual labor, as opposed to the shorter versions worn by workers for practicality.

Similarly, the himation, when draped in elaborate folds, could indicate a level of sophistication and a lack of manual labor, while a plain, undyed himation might be worn by the common populace.

Even the state recognized the importance of clothing as a marker of social status.

Sumptuary laws were sometimes enacted to regulate the extravagance of dress and ensure that luxury in attire was reserved for the upper echelons of society.

These laws could dictate who could wear certain colors, such as the Tyrian purple, or how much jewelry could be displayed in public.

Jewelry, shoes, hats, and other accessories

Footwear in ancient Greece was relatively simple and functional, yet it also carried connotations of status and occasion.

Sandals, the most common form of footwear, were made from a flat sole that was strapped to the foot with leather thongs.

These were suitable for the warm climate and varied from plain designs for the common people to more luxurious versions for the wealthy, which might be adorned with precious metals or intricate designs.

Boots, which covered more of the foot and ankle, were also worn, particularly for travel or during colder weather, and by certain professionals like horsemen, who required more robust footwear.

The wide-brimmed petasos hat was worn by both men and women for protection against the sun, and it was particularly associated with travelers and hunters.

It could be fastened under the chin and was typically made of straw or felt.

Jewelry played a significant role in ancient Greek fashion, with both men and women adorning themselves with earrings, bracelets, necklaces, and rings.

These items were crafted from a variety of materials, including gold, silver, bronze, and semi-precious stones.

Jewelry often depicted gods, goddesses, and mythological scenes, serving as a form of storytelling and expression of religious devotion or superstition.

For women, jewelry was a key part of their dowry and was indicative of their family's wealth and status.

Belts and girdles were also common, used to cinch the waist and secure garments in place.

They could be simple leather straps or elaborately decorated pieces of fabric, sometimes even adorned with gold or silver.

These accessories were not just functional; they also accentuated the body's form and could be used to adjust the drape and fit of garments, allowing for a degree of personalization in the silhouette of the clothing.

Other accessories included hairpins and brooches, which were utilitarian as well as ornamental, used to secure garments or hairstyles.

Did ancient Greek clothing have patterns or colors?

The visual allure of ancient Greek clothing was significantly enhanced by the use of patterns, colors, and decorations, which were imbued with cultural significance and aesthetic value.

Patterns in Greek attire were often geometric, featuring checks, stripes, and meanders, reflecting the Greeks' love for symmetry and balance.

These patterns could be woven into the fabric or embroidered after the garment was constructed, adding texture and visual interest.

Borders and edges of garments, particularly the himation and peplos, frequently displayed such patterns, providing a striking contrast to the otherwise plain cloth.

Color played a vital role in the visual language of ancient Greek clothing. Natural dyes extracted from plants, minerals, and sea creatures yielded a palette that included reds from madder root, yellows from saffron, blues from woad, and the rare and expensive purple from the murex snail.

The intensity of the color often correlated with the wearer's social status; for example, bright and deep hues were typically reserved for the affluent and the noble, as they were more costly and labor-intensive to produce.

White, the natural color of wool and linen, was also popular, particularly in the summer months, and was associated with purity and simplicity.

Embroidery adorned various parts of garments, often highlighting the edges or hems.

These embroidered embellishments could depict a range of motifs from Greek mythology, nature, or daily life, serving not only as decoration but also as a narrative element or a talisman against misfortune.

The Greeks also appreciated the aesthetic of pleating, which added volume and a play of light and shadow to their garments, creating a dynamic visual effect as the wearer moved.

How ancient Greek clothing styles changed over time

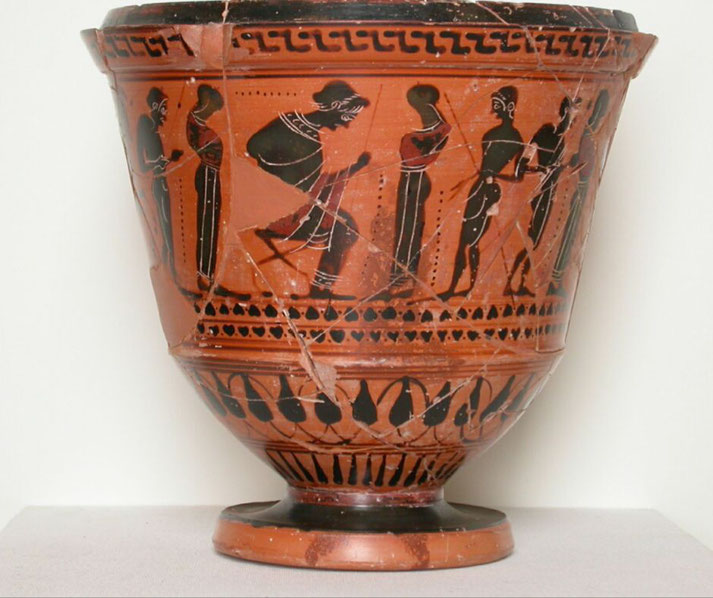

In the early periods, such as the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations which flourished between 2000 and 1100 BCE, clothing was often more form-fitting, designed to accentuate the human figure. This trend is vividly depicted in frescoes from Knossos and Pylos, and pottery from the era.

The Minoans, for example, are known for their complex layered skirts and tightly fitted bodices, which were later simplified into the more draped and fluid styles that became characteristic of classical Greek fashion.

As Greek society transitioned into the Archaic and Classical periods, the clothing became more standardized with the introduction of the chiton and himation, which were favored for their versatility and ease of wear.

The Doric chiton, an earlier version, was made from a woolen rectangle and fastened with pins at the shoulders.

Over time, this evolved into the Ionic chiton, which was longer, had sleeves, and was made from lighter materials like linen, reflecting a shift towards more intricate and delicate styles.

The Hellenistic period brought further changes, influenced by the expansion of the Greek world and the cultural exchanges that came with Alexander the Great's conquests in the 4th century BCE.

Eastern influences began to appear in Greek clothing, with the introduction of new patterns, colors, and the diaphanous fabrics that were favored in the courts of the East.

Garments became more elaborate and luxurious, with increased use of draping techniques that allowed for more complex and flowing silhouettes.

Throughout these periods, the social and political climate of Greece also played a role in the evolution of clothing.

The democratic ideals of the Classical period, for example, promoted a certain level of simplicity and uniformity in dress, to reflect the egalitarian ethos of the city-state, particularly in Athens.

In contrast, the opulence of the Hellenistic period mirrored the wealth and cosmopolitan nature of a society that had become an empire.

The influence of Greek clothing did not wane with the decline of the Greek city-states; rather, it was absorbed into the Roman Empire, where it continued to evolve and shape fashion.

The Roman toga, for instance, was a descendant of the Greek himation, and the synthesis of Greek and Roman attire would lay the foundation for the development of Western fashion traditions.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.