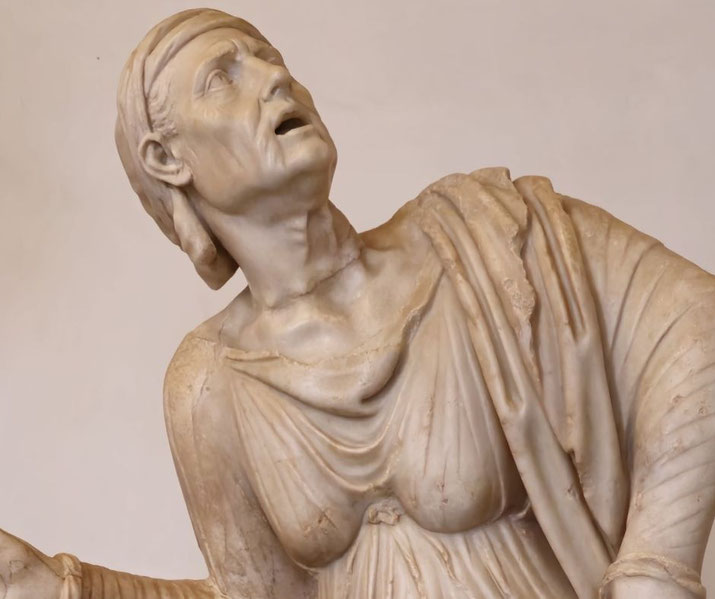

Daughters, wives, mothers: What was life like for women and girls in ancient Rome?

Women have always played pivotal roles in society, though these roles have varied widely based on cultural norms, societal expectations, and historical context.

In ancient Rome, a civilization known for its vast empire, groundbreaking legal system, and influential arts, women's roles were quite complex.

Despite living in a patriarchal society where public life was dominated by men, Roman women were far from silent spectators.

In fact, a number of them would leave a distinct mark on the Empire's history.

Ancient Roman society's expectations of women

The society of ancient Rome was deeply hierarchical, with clearly demarcated strata based on birth, wealth, and political power.

At the heart of this social system was the concept of 'paterfamilias', a family structure in which the eldest male held absolute power over his family, including his wife, children, and slaves.

Similarly, Roman society was fundamentally patriarchal, with men occupying most public roles and wielding significant authority.

They held all political power, conducted business, and participated in civic duties.

This structure was underpinned by the Roman legal system, which viewed women as perpetually under the guardianship of a man, be it a father, husband, or other male relative.

However, despite the dominance of men in most spheres, women were still integral to the social, economic, and cultural life of Rome.

In the domestic sphere, they were responsible for managing households, raising children, and maintaining family traditions.

In the public realm, women were sometimes prominent in religious rites and festivals, often serving as priestesses.

Some women, particularly those from wealthier families, had access to education and enjoyed a degree of autonomy in managing their wealth.

However, the social expectations of women varied greatly depending on their social status.

Elite women, for instance, were expected to embody the ideal of 'matronly virtue', which included modesty, loyalty, and devotion to family.

Meanwhile, women from the lower classes had to balance family responsibilities with work outside the home.

It is worth noting that Roman society evolved significantly over time, spanning the Kingdom, Republic, and Imperial periods, each with its own shifts in societal norms and gender roles.

As a result, women's roles, rights, and expectations shifted within these broad historical arcs.

What it was like to grow up as a girl in Ancient Rome

Young girls in Rome were brought up under the firm hand of the paterfamilias, the family patriarch.

From their earliest years, they were groomed to fit into the sociocultural norms and to prepare for their future roles as wives and mothers.

The first few years of a Roman girl's life were spent in the care of her mother and female relatives.

As they grew, they were taught household chores, such as cooking, cleaning, and weaving, essential skills expected of a Roman matron.

Some girls from affluent families also had wet nurses and, later, tutors.

The education of girls in ancient Rome was a contested subject. While formal education was traditionally reserved for boys, over time, some girls, particularly from the upper classes, were given access to basic education.

Their curriculum was typically centered around reading, writing, and arithmetic, equipping them with essential skills for managing a household and participating in society.

It was not uncommon for girls to be educated in the arts. They were taught music, dancing, and sometimes even literature.

Understanding and appreciating poetry was considered a virtue for a Roman woman.

In contrast, girls from lower socio-economic backgrounds may not have had the opportunity for formal schooling and instead focused on acquiring practical skills to help their families.

Coming of age was a significant milestone in a Roman girl's life, which involved a series of rituals and ceremonies.

The transition from girlhood to womanhood, typically around the age of twelve to fourteen, was celebrated by the festival of Liberalia.

On this day, girls would discard their childhood token, the 'bulla', signaling their readiness for marriage and motherhood.

Marriage and family life in Ancient Rome

The institution of marriage was not as much about love as serving as a conduit for the protection of property, wealth, and social status.

For Roman women, marriage shifted the focus of their responsibilities from their birth family to their new husband's home.

Typically, Roman girls were married off at a young age, often in their early teens, to much older men.

The age disparity between spouses reflected the societal expectation of the husband as the provider and the wife as the caretaker of the home.

Additionally, marriages were usually arranged by families and partners were often chosen based upon the other family's perceived wealth and social standing.

Most families wanted to marry into another that was more rich and powerful than their own.

Roman marriages were generally monogamous, but the expectations of a Roman wife were numerous.

They were to manage the household, raise children, and support their husband's career.

Furthermore, they were to uphold the ideal of 'univira', the virtue of being married to one man for life.

However, the marital relationship was not simply one of domination and submission.

Roman matrimony, particularly in the upper classes, often involved a degree of partnership.

Wives were frequently their husbands' confidantes and advisors, given the task of managing significant portions of the family's wealth and assets.

While legally under their husband's authority, some women wielded considerable influence within their marriages.

Family life was considered to be central to a Roman woman's existence. Mothers were primarily responsible for rearing their children, overseeing their education, and instilling moral values.

The strength of maternal affection was praised in Roman society, with mothers like Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi, being revered for their devotion to their children.

Divorce, though not common, was legally possible in Rome and could be initiated by either party.

Women retained their dowries after divorce, which provided them some financial security.

However, the societal stigma attached to divorce often acted as a deterrent.

What protections did women have in Roman law?

Under the Roman legal system, women occupied a unique and somewhat paradoxical position.

They were eternally considered under the guardianship of men, yet they could enjoy a level of financial independence unusual for the time.

In the early Roman society, women were considered legally incompetent and required a guardian, usually a male relative, to represent them in all legal matters.

This guardian held 'patria potestas', or 'power of the father', which gave them control over property and decisions regarding marriage, divorce, and even life and death.

It is important to note that the legal position of women did gradually evolved, even if it was only in a limited way.

For example, under the Augustan marriage laws, women who had a certain number of children (three for Roman citizens, four for freedwomen) were granted 'sui iuris' status, allowing them to be legally independent from their guardians.

Laws like this aimed to encourage marriage and childbirth among the upper classes, but they also inadvertently expanded women's legal autonomy.

Also, Roman law permitted women to own, inherit, and dispose of property, providing them with a degree of financial independence.

Elite women, especially, could control considerable wealth, using it to even influence politics, fund public works, and sponsor the arts.

However, their property rights were often tempered by societal expectations of modesty and subordination to male authority.

Unfortunately, Roman women could not hold political office or vote. Nonetheless, some women still had significant power behind the scenes, influencing politics through their familial and social connections.

In terms of criminal law, women were subject to the same penalties as men, with some exceptions.

Adultery laws, for instance, were decidedly skewed, heavily punishing adulterous wives while largely overlooking the infidelities of husbands.

The secret economic power of Roman women

In the bustling economic landscape of ancient Rome, women's contributions often remained in the shadows, overlooked yet indispensable.

From the elite matron managing her household to the slave girl laboring in fields, Roman women of all social strata were engaged in economic activities that kept the wheels of the Roman economy turning.

At the most basic level, women's economic roles were deeply intertwined with their domestic responsibilities.

Managing a Roman household, particularly those of the upper classes, required significant organizational skills.

Women were in charge of supervising slaves, preserving food, spinning wool, weaving fabric, and caring for children and the sick.

These tasks, essential for the sustenance of the family and society, were often undervalued as they were unpaid and performed within the private space.

However, women, particularly those from the lower classes, worked to support their families.

They were involved in a wide range of occupations, including farming, midwifery, selling goods in the market, baking, and washing clothes.

Some could even be involved in professions typically dominated by men, such as medicine and merchant trade.

A number of Roman women also own businesses. Inscriptions and records reveal women as owners of shops, taverns, and small factories.

They could also engage in contracts, lend money, and invest in ventures, often handling the financial affairs of their households.

Enslaved women, a considerable portion of the Roman population, were involved in various forms of labor, including agricultural work, craft production, and domestic service.

Despite their lack of personal freedom, their labor was vital to the functioning of the Roman economy.

How women played a role in Roman politics

While the political arena in ancient Rome was ostensibly the domain of men, women too found ways to make their influence felt.

Their influence was often exerted indirectly, through their relationships with husbands, sons, or other male relatives.

Noble women, in particular, held a unique position. They could use their wealth, social status, and networks to influence political decisions and advance their family's interests.

Some even became political symbols in their own right. An excellent example is Livia Drusilla, wife of Augustus, the first Roman Emperor, who leveraged her role as the imperial wife to accumulate considerable power and influence.

Women also influenced politics by rallying public opinion and, at times, even organizing protests.

A notable example is the protest against the Oppian Law in 195 BC, when Roman women successfully campaigned for the repeal of a law that restricted their use of luxury goods.

This event, although exceptional, demonstrates that women could and did directly affect political outcomes.

In religion, women could serve as priestesses, participating in religious rites and public festivals.

The Vestal Virgins, priestesses of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, held a unique position in Roman society.

They were accorded numerous privileges, including the ability to manage their property and move freely in public, contrasting with the restrictions faced by most Roman women.

Public life also extended to social gatherings, such as banquets and festivals, where women could participate alongside men, engaging in conversations and networking.

Such events provided women with opportunities to build alliances and exercise soft power.

How women dressed and why this mattered

In the vibrant society of ancient Rome, dress and personal adornment served as significant indicators of identity, status, and morality.

For Roman women, their attire was a reflection of their social position and marital status.

The staple of Roman women's clothing was the 'stola', a long, sleeveless tunic worn over a 'tunica intima', a type of undergarment.

It was usually made of wool or linen and was belted at the waist, creating a bloused effect.

It was the typical dress of a respectable married woman, symbolizing her modesty and fidelity.

Unmarried girls, on the other hand, typically wore a 'toga praetexta', a toga with a purple border that was also worn by young boys.

Upon marriage, they transitioned to the stola. Meanwhile, the 'toga', typically associated with Roman men, was also worn by women, but only certain categories: prostitutes, for instance, were required to wear the toga as a sign of their profession.

Beyond these basic garments, women's attire could be adorned with various accessories, such as brooches and belts, to accentuate their style.

Jewelry was also common, with rings, bracelets, necklaces, and earrings being worn by women across different social classes.

The material of the jewelry, however, was indicative of the wearer's wealth.

Women of the upper classes donned jewelry made of gold, silver, and precious stones, while those from the lower classes wore items made of bronze, glass, and bone.

Complex and elaborately styled hair was a mark of a woman's status and wealth, as such hairstyles required time and the help of slaves to create.

Some Roman women dyed their hair, used wigs, and even curled their hair with irons.

Cosmetics were used as well, including creams, rouge, and kohl, despite the societal expectation of natural beauty and modesty.

Famous Roman women who changed history

While ancient Rome was a society dominated by men, a number of women managed to rise above societal constraints to make significant marks on Roman history.

One such woman was Cornelia Africana, mother of the Gracchi brothers, who were well-known politicians in the late Roman Republic.

Cornelia was revered not only for her sons but also for her wisdom, virtue, and devotion to her family.

She famously rejected a marriage proposal from the King of Egypt after her husband's death, choosing to dedicate herself to her children's education.

Livia Drusilla, later known as Julia Augusta, was another influential figure. As the wife of the first Roman emperor, Augustus, played an essential role in supporting and advising her husband, managing their large household, and later acting as a counselor to her son Tiberius when he became emperor.

Her image as the ideal Roman matron, symbolizing virtue and traditional values, was widely propagated.

Agrippina the Younger, mother of Emperor Nero, was infamous for her political maneuvering and ambition.

She was instrumental in securing the throne for her son and initially served as his advisor during the early years of his reign.

Although she was ultimately murdered by her son, her influence and political acumen marked a high point in the power of women in the Roman imperial court.

Finally, Fulvia, the wife of Mark Antony, is another example of a powerful woman.

Known for her political ambition, she exerted considerable influence during the late Roman Republic's tumultuous years.

Fulvia is famous for her political involvement and even raising an army during the Perusine War, marking her as one of the most politically active women of the Roman Republic.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.