Was Atlantis real? Everything we currently know about this mysterious ancient city

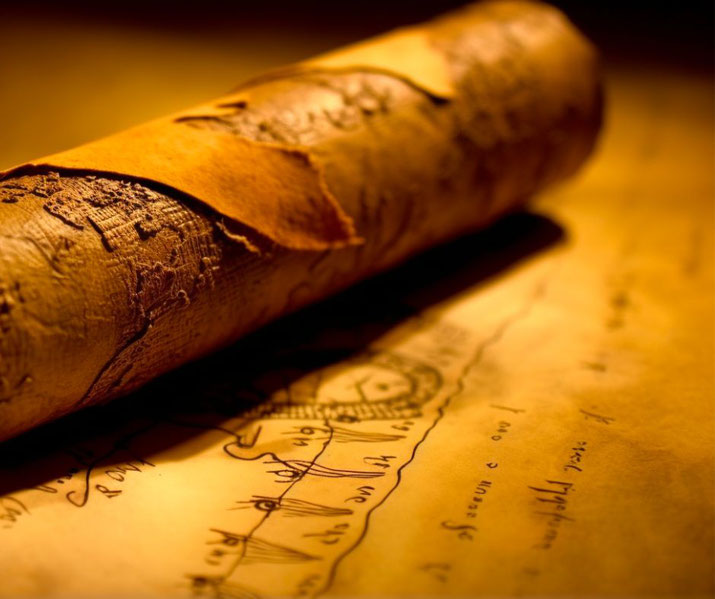

Somewhere beyond the Pillars of Hercules, a highly developed society is said to have sunk beneath the sea. This story, first told by Plato as Atlantis, has sparked debates over whether it was an actual place, a written lesson, or a distant prehistoric memory.

But perhaps the real question is: why has this tale of disaster continued to be so popular for so long?

The very first historical evidence of Atlantis

The story of Atlantis comes from two books by the ancient Greek thinker Plato: Timaeus and Critias.

He wrote these dialogues around 360 BCE, when Athens was rebuilding after the Peloponnesian War.

In Timaeus, Plato describes a talk between Socrates, Timaeus, Hermocrates, and Critias.

In that dialogue, Critias tells the story of Atlantis, saying it was passed to him by his family from the Athenian lawmaker Solon.

Solon is said to have learned of Atlantis from Egyptian priests in the city of Sais during his journey to Egypt around 590 BCE.

According to them, there was a great society that lived about 9,000 years before their time, placing it around 9,590 BCE.

In the Critias dialogue, Plato goes deeper into the description of Atlantis, explaining its layout, government, and downfall.

Specifically, the large island was said to be beyond the “Pillars of Hercules.”

The people of Atlantis were a strong naval power that conquered parts of Europe and Africa before the ancient Athenians stopped them.

In addition, Atlantis was said to have an army of 5,000 chariots and a navy of 1,200 ships.

Plato also described Atlantis as a place of great wealth, with natural resources including gold, silver, and orichalcum, a metal said to shine like fire.

However, their fall happened suddenly. In one day and night, a series of strong earthquakes and floods caused Atlantis to sink beneath the sea, leaving only stories behind.

The physical description of Atlantis

Plato’s descriptions of Atlantis give a surprisingly detailed description of its layout.

The centre of the city was surrounded by circular rings of water and land. These rings were apparently connected by tunnels wide enough to hold ships, making sea travel easy.

As a result, the main city was a key centre of trade activity. Curiously, Plato goes on to say that the city was located on a flat area surrounded by mountains that sloped to the sea.

This flat area was said to be 3,000 stadia long and 2,000 stadia wide, and watered by a system of canals. For reference, a stadia is an old Greek measurement, about 150–210 m.

In fact, Plato wrote that the surrounding mountains were taller than any known to the ancient Greeks, which may have been to emphasise their metaphorical importance rather than giving exact geological facts.

Meanwhile, at the very centre of the rings stood a hill where a palace was built for the first king of Atlantis, Atlas, from whom it got its name.

Around this hill were constructed walls of different kinds of coloured stone: red, white, and black.

These were tought to have been mined from nearby mountains and valleys.

These walls were also decorated with precious metals, as a sign of the island’s great wealth.

Beyond the main city, the rest of Atlantis was split into ten regions. Plato said the each of these regions had very fertile land that was well watered, with natural springs and rich soil that grew two crops a year.

Who lived in Atlantis?

The society and culture of Atlantis, as shown by Plato, displayed a society of great complexity and power.

Its political system was set up around the ten regions, each led by a king who was a child of its divine founders.

These kings would meet in the main city to discuss laws, make final decisions, and discuss war and peace.

Their decisions were considered to be absolute, and they swore oaths to abide by its laws and customs.

Because of this naval strength, Atlantis controlled the seas, setting up trade routes and influencing large areas.

Plato describes Poseidon as the divine father of its royal family. Accordingly, the people built a large temple for this god.

However, over successive generations, Plata says that the moral strength of their society began to weaken, which he believes was the real cause of their downfall.

He describes a decline in goodness and honesty among the people. Soon, the divine part of their bloodline faded, along with it their good qualities.

As a reuslt, the people of Atlantis became greedy for power, and dishonest, leading to fights inside and attacks on others.

The real location of Atlantis

While Plato’s account is our main source of information about this lost society, the lack of real evidence and the tempting nature of the tale have led many to share different ideas about where it might have been.

Some people suggest it was in the Mediterranean, pointing to places like Santorini, which had a huge volcanic eruption around 1600 BCE.

This eruption and the following tsunami could have led to the dramatic destruction of a city.

The island of Santorini, known in ancient times as Thera, has been studied by many researchers.

Dig sites in the area have actually found evidence of a developed society, with detailed buildings and objects, but no evidence directly links these finds to Atlantis.

The huge volcanic eruption mentioned about, that has been dated around 1600 BCE, seems to have also help contribute to the end of the Minoan society.

This had led some to think it could have led to the story of Atlantis itself.

However, there are other areas off the coast of Spain have also been of interest.

Plato’s reference to Atlantis being beyond the “Pillars of Hercules” is seen as a way of mentioning the Strait of Gibraltar in Spain. However, no historical evidence supports a city there.

Another idea says that Atlantis was in the Americas, especially in the Caribbean or around the Bahamas.

The discovery of the Bimini Road, a rock formation underwater recorded in 1968, caused excitement among fans of this proposal.

Some thought these straight stone lines could be remains of the lost city. Even so, earth science studies have shown that these formations are natural, not man-made.

Finally, the idea that Atlantis might be in Antarctica has also gained some notice.

Supporters say the continent may once have been free of ice and could have had people living upon it.

However, earth and ancient climate evidence shows that Antarctica has been covered in ice for over 34 million years, making a developed society of humans there impossible.

In recent years, some researchers have looked at satellite images and done remote sensing studies to find unusual formations on the ocean floor.

Even so, no reliable scientific study has confirmed any man-made or Atlantean structures.

Difficulties facing historians and archaeologists

While the tale of Atlantis has held our interest for a very long time, it has faced a lot of doubters.

Many historians think that the story, as given by Plato, should not be taken as historical fact but rather as a written object lesson or morality tale.

One of the main criticisms is the lack of records or mentions of Atlantis outside Plato’s writings.

That absence is especially striking because, given the supposed size, power, and influence of its society, no other ancient texts or records, whether Greek or from nearby societies, mention such a people.

Another doubt is the timeline given by Plato. According to his writings, Atlantis existed about 9,000 years before Solon’s time, placing the society around 9,590 BCE.

That would place it before most known ancient societies and flies in the face of all of our current ideas regarding human development at that time.

Also, the detailed and specific nature of his account, especially about measurements, layout, and government, suggests a story or lesson rather than strict history.

Indeed, some historians say that he used the story to express ideas about government, right and wrong, and the dangers of excessive national pride.

As a result of these concerns, the search for a real Atlantis is often seen more as a romantic quest than a serious historical or archaeological effort.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.