How Octavian crushed the combined forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at Actium

On a single day in September of 31 BCE, the adopted son of Julius Caesar faced off against a massive fleet assembled by Mark Antony and Queen Cleopatra on the waters off the western coast of Greece.

This was a high stakes event, with both sides commanding vast resources. The ultimate victor of this battle would secure their position as Rome's unchallenged leader over the Roman Republic.

To the shock of many, the youngest of the combatants, Octavian would gamble everything to achieve a triumph.

Why were Octavian and Mark Antony at war with each other?

After the sudden assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, Rome descended into chaos as both his supporters and enemies vied for control.

Octavian, who was announced as Caesar's adopted son and heir, initially formed an uneasy alliance with Mark Antony and Lepidus in 43 BCE, known as the Second Triumvirate.

This alliance, however, proved fragile as personal ambitions and mutual distrust strained their attempts at cooperation.

By 40 BCE, Antony had established himself in the eastern provinces of the Roman Republic, while Octavian solidified his power in the west.

Antony formed a personal alliance with Cleopatra, the powerful queen of Egypt.

News of this agreement only deepened the rift between Antony and Octavian. In 36 BCE, tensions escalated when Octavian launched a propaganda campaign against Antony, portraying him as a traitor who had abandoned Roman values for the decadent luxuries of the East.

With the full support of the Roman Senate, Octavian formally declared war on Cleopatra in 32 BCE, which effectively challenged Antony as well.

How both sides prepared for the final showdown at Actium

Octavian and Antony made extensive preparations for what they knew would be a decisive battle at Actium.

Octavian turned to the support of his most trusted general and friend Agrippa. He suggested focusing on securing control of the Adriatic Sea to cut off Antony’s supply lines.

To this end, Agrippa captured the important ports of Methone in 31 BCE and Corcyra (modern Corfu).

This provided Octavian with strategic naval bases from which he could launch his attacks.

Antony, meanwhile, concentrated his efforts on gathering a large fleet and a substantial army at the Gulf of Ambracia near Actium.

He chose this location for its defensible position, as he hoped to lure Octavian into a protracted siege that would favor his numerically superior forces.

Cleopatra contributed a significant portion of Antony’s naval power by adding her Egyptian ships to the already impressive armada.

Aware of the plan against them and how it was intended to trap them, Octavian and Agrippa ensured that Antony’s own forces remained confined within the Gulf of Ambracia.

This meant that he was unable to fully utilize their numerical advantage. By August 31 BCE, both sides were entrenched, and Octavian’s forces maintained a blockade that steadily drained Antony’s resources.

As a result, Antony and Cleopatra had limited options. Faced with dwindling supplies and growing unrest within his ranks, Antony found himself forced into a position where he would have to either break the blockade or risk losing everything.

How much stronger were Antony’s forces before the battle?

The size of the naval forces at play in the Battle of Actium were among the largest that the ancient world had ever seen.

Octavian commanded a fleet of approximately 400 ships, which was supported by around 80,000 infantry.

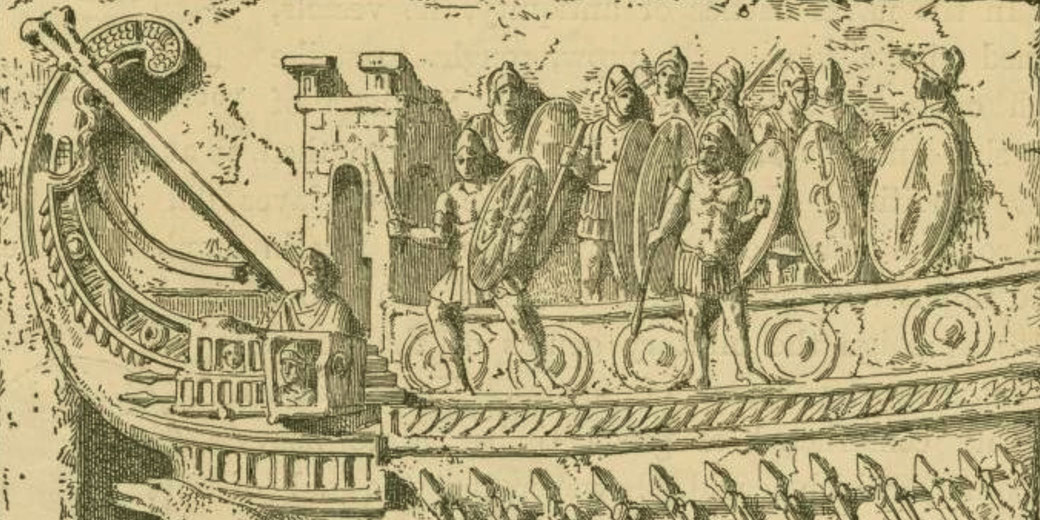

These ships were mainly war galleys called liburnians, which were smaller and more maneuverable than Antony’s larger quinqueremes and triremes.

Agrippa operated as the fleet’s admiral and Octavian had paid well to ensure that these vessels were equipped with experienced crews.

Antony, by contrast, amassed a much larger fleet of about 500 ships, in addition to 60,000 infantry and 12,000 cavalry.

In fact, many of these ships were provided by Cleopatra herself. Antony’s fleet included the massive quinqueremes, which were the most dangerous of ships during that era since they were heavily armed and capable of carrying more soldiers.

These ships, though slower, were designed to overpower enemy vessels through sheer force.

However, the size and weight of these ships could mean that they were less effective in confined waters where maneuverability was difficult.

What happened at the Battle of Actium?

On the morning of September 2, 31 BCE, with both fleets were positioned off the coast of western Greece near Actium.

Octavian’s forces under Agrippa held the advantage in positioning, since they had been successfully blockading Antony’s fleet within the Gulf of Ambracia.

The battle started when Antony attempted to break through the blockade, spearheaded by his larger and heavily armed quinqueremes in a direct assault.

These ships charged forward but quickly found that they struggled to maneuver in the restricted waters.

In contrast, Agrippa’s smaller and more agile ships saw that they could begin to exploit this vulnerability.

However, Antony’s greater number of ships was able to counter the initial responses from Octavian’s fleet for a few hours.

As a result, it was not clear which side was gaining a decisive upper hand. However, the tide began to turn when Cleopatra, stationed at the rear of Antony’s fleet with her Egyptian ships, made a sudden and unexpected decision.

Apparently, without a clear signal from Antony, she ordered her ships to retreat from the battle.

This meant that a large portion of Antony’s fleet followed her, which created confusion and chaos among his remaining forces.

Many historians believe Cleopatra’s withdrawal stemmed from a pre-arranged plan with Antony, while others argue it resulted from her personal decision to abandon a losing cause.

Regardless of the cause, the consequences were immediate and disastrous for Antony.

With Cleopatra’s forces in retreat, Antony’s remaining ships found themselves overwhelmed.

Octavian’s fleet gradually encircled and the disorganized remnants of Antony’s navy and began destroying ships.

As the afternoon wore on, Antony quickly realized the battle was lost and he fled the battlefield in a small ship to join Cleopatra.

Their remaining forces, now leaderless and demoralized, surrendered.

Why did Antony and Cleopatra lose at Actium?

Ultimately, there were a number of key factors that contributed to Octavian’s decisive victory at the Battle of Actium.

One of the most significant advantages was the strategic brilliance of Agrippa, who had decided to blockade Antony’s forces within the Gulf of Ambracia.

This cut off his enemy’s vital supply lines which weakened Antony’s ability to sustain his large fleet and to keep the initiative.

As a result, Octavian’s forces maintained a persistent pressure on Antony, which eventually forced him into a battle under unfavorable conditions.

Also, the superior maneuverability of Octavian’s fleet in comparison to Antony’s larger quinqueremes was the biggest factor on the day of battle.

The advantage in sheer size and power of the quinqueremes would have been devastating if they had met on open waters.

However, they were more of a liability in the confined waters where the battle took place.

As a result, Octavian’s smaller and more agile ships, along with their experienced crews, were able to maximize on this fact to effectively outmaneuver and outflank Antony’s forces.

Consequently, they were able to exploit gaps in Antony’s formation quicker than their opponents could respond to.

This tactical superiority neutralized Antony’s numerical advantage.

Finally, Antony’s strategic miscalculation of relying too heavily on Cleopatra’s support backfired when she unexpectedly withdrew from the battle.

After this point, there wasn’t much more Antony could do to turn the tide back in his favor.

The confidence of his remaining forces vanished, and they became easy targets. It was the psychological impact of this betrayal that was the final nail in the coffin that led to the rapid collapse of Antony’s resistance.

Why the Battle of Actium was so significant

Following his victory at Actium, Octavian wasted no time in capitalizing on his success.

He pursued Antony and Cleopatra to Alexandria, where the two sought refuge. On August 1, 30 BCE, Octavian’s forces entered the city, and Antony, realizing the futility of further resistance, took his own life.

Shortly after, Cleopatra followed suit, choosing a noble death over a humiliating submission to Rome.

Their deaths effectively ended the last significant challenge to Octavian’s authority.

With Antony and Cleopatra out of the way, Octavian turned his attention to consolidating power.

In September 30 BCE, he annexed Egypt as a Roman province. This brought the wealth of the Nile under his direct control.

The immense wealth of Egypt’s agricultural output flooded into Rome’s treasury, which also enabled Octavian to reward his loyal soldiers.

In addition, Egypt’s steady supply of grain would become crucial for maintaining social stability in Rome.

Octavian’s control over Egypt marked the beginning of his transformation from a military leader into a statesman, as he carefully managed the integration of this rich and powerful territory into the Roman state.

By 27 BCE, the Senate granted him the title of Augustus: a moment that historians now point to as the formal end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.