How to become an ancient Roman emperor: Your essential step-by-step guide

The Roman Empire, spanning vast territories and influencing countless cultures, remains one of history's most formidable and captivating empires.

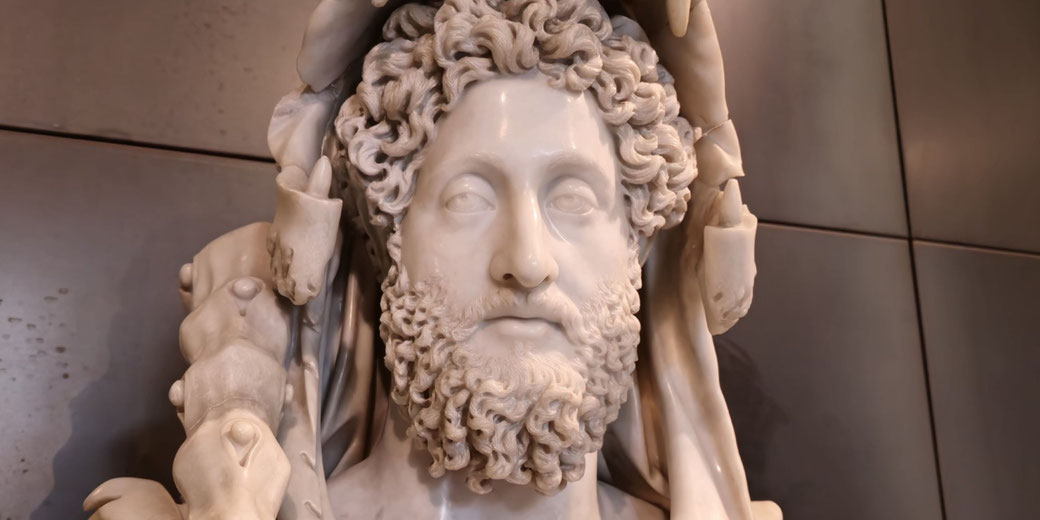

Central to its governance and legacy was the role of the emperor, a position that held not only political power but also immense cultural and religious significance.

The journey to becoming an emperor was not very straightforward. It was often shaped by political maneuvering, military prowess, popular support, and sometimes, sheer luck.

While some ascended the throne through legal and traditional pathways, others took more tumultuous routes, marked by usurpation, civil wars, and military endorsements.

How the role of emperor was developed

The Roman Empire's roots trace back to the establishment of the Roman Republic in 509 BCE, following the overthrow of the last Roman king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus.

For nearly five centuries, Rome was a republic, governed by elected officials and a Senate that represented the interests of its patrician class.

However, as Rome expanded its territories, internal strife and external threats began to challenge this republican model.

The late republic, particularly in the 1st century BCE, witnessed a series of civil wars and power struggles.

Julius Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon River in 49 BCE, which led to a civil war against the Senate and his eventual dictatorship, signaled a significant shift in Rome's political landscape.

His assassination in 44 BCE and the subsequent power struggles among his successors, notably between Mark Antony and Octavian (later Augustus), further destabilized the republic.

The culmination of these events was the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, where Octavian defeated Antony and Cleopatra, consolidating his power.

By 27 BCE, Octavian, now bearing the title Augustus, effectively transformed the republic into an empire, becoming its first emperor.

Under Augustus, the empire experienced relative peace, known as the Pax Romana, which lasted for over two centuries.

However, the means by which one became emperor evolved over time. While Augustus came to power through a combination of political savvy, military strength, and familial ties, his successors would find their paths to the throne influenced by various factors, from military endorsements to the whims of the Roman populace.

The empire's vastness and diversity, coupled with its evolving political structures, ensured that the journey to the imperial throne was never straightforward and was often fraught with challenges.

Option 1: Legal and Traditional Pathways

Within the framework of the Roman Empire, there existed recognized legal and traditional pathways to ascend to the position of emperor.

One of the most prominent methods was through adoption. Emperors, often without biological heirs or seeking to ensure a smooth transition of power, would adopt capable and politically astute individuals as their sons.

This practice was not just a matter of personal choice but was deeply rooted in Roman tradition.

Augustus, the first Roman emperor, set this precedent by adopting Tiberius, ensuring a continuation of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

This method of succession through adoption was seen as a way to select the most competent successor rather than leaving the empire's fate to the uncertainties of biological inheritance.

Another traditional pathway was the acclamation by the Senate. While the Senate's power had diminished compared to its stature during the Republic, it still held ceremonial and symbolic importance.

The Senate's endorsement provided a veneer of legitimacy to the emperor's rule.

Emperors sought and, in most cases, received the Senate's approval, even if the real power dynamics lay elsewhere.

While these pathways provided a semblance of order and tradition to the process, the reality was often more complex.

The interplay of personal ambitions, political alliances, and the ever-present military factor meant that the journey to the imperial throne was as much about navigating these established routes as it was about understanding and manipulating the nuanced power dynamics of the empire.

Option 2: Acclamation from the Legions

The military's role in the Roman Empire was paramount, not just in terms of defending borders and conquering new territories, but also in determining who would wear the imperial purple.

The legions, spread across the vast expanse of the empire, were more than just fighting forces; they were significant political entities.

A general who had the loyalty of his troops could wield immense power, often rivaling that of the sitting emperor.

One of the most direct ways the military influenced the imperial seat was through acclamation.

When a general was proclaimed "Imperator" by his troops, it was both an acknowledgment of his military successes and a declaration of their loyalty to him as a leader.

This acclamation by the legions was a powerful endorsement, and in many cases, it was the first step toward a general's march on Rome to claim the throne.

Vespasian, for instance, was in Judea when he learned that legions in Egypt, then a crucial grain supplier to Rome, had declared him emperor in 69 CE.

This military backing was instrumental in his eventual rise to power during the Year of the Four Emperors.

The Praetorian Guard, stationed in Rome, held a unique position in this dynamic. Originally established as an elite unit to protect the emperor, the Praetorians evolved into powerful kingmakers.

Their proximity to the seat of power and their role as the emperor's personal bodyguards gave them unparalleled influence.

There were instances, such as the assassination of Emperor Pertinax and the subsequent auctioning of the imperial title to the highest bidder in 193 CE, where the Praetorian Guard directly intervened in the selection of the emperor.

However, this military influence was a double-edged sword. While the support of the legions or the Praetorian Guard could elevate an individual to the highest echelons of power, it also meant that emperors constantly had to ensure their loyalty, often through bonuses and pay raises.

Emperors who lost the military's support found themselves in precarious positions, highlighting the delicate and sometimes volatile relationship between the throne and the barracks.

Option 3: Usurpation and Civil War

The path to the Roman imperial throne was not always paved with tradition and ceremony.

Often, it was carved out through force, ambition, and political opportunism. Usurpation, where an individual seized power unlawfully, was a recurring theme in the empire's history, reflecting the intense competition and the high stakes associated with the imperial title.

One of the most tumultuous periods in Roman history was the Year of the Four Emperors in 69 CE.

Following the suicide of Nero, a power vacuum emerged, leading to a rapid succession of emperors, each vying for control.

Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian all laid claim to the throne within a single year, with each ascent and descent marked by treachery, alliances, and battles.

It was a year that showcased the fragility of the imperial system when multiple contenders, backed by different factions of the military, sought to claim the throne.

Civil wars were another manifestation of these power struggles. The Roman Empire, with its vast territories and diverse populations, was often a cauldron of competing interests.

Generals, with legions loyal to them, would sometimes challenge the reigning emperor, leading to protracted and devastating conflicts.

The civil war between Mark Antony and Octavian, culminating in the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, was not only a personal rivalry but also a clash of visions for the empire's future.

Octavian's victory solidified his position, leading to the establishment of the Principate and the beginning of the imperial era.

Option 4: Claim to be a god

The concept of divinity played a pivotal role in the Roman understanding of leadership and authority.

Emperors were not just political leaders; they were often intertwined with the spiritual and religious fabric of the empire.

This intertwining served both as a tool of governance and a reflection of the empire's evolving religious landscape.

From the earliest days of the empire, the notion of divine right was employed to legitimize and solidify an emperor's rule.

Augustus, the first Roman emperor, skillfully used religious imagery and associations to bolster his position.

He presented himself as the "son of a god," referencing the posthumous deification of his adoptive father, Julius Caesar.

By doing so, Augustus not only enhanced his own stature but also established a precedent where the emperor was seen as having a unique, divinely ordained role in the governance and protection of the empire.

As the empire matured, the practice of deifying deceased emperors became more common.

Upon their death, and often after a decree by the Senate, emperors were elevated to godhood, with temples built in their honor and priests dedicated to their worship.

This deification served multiple purposes. For the populace, it provided continuity and a sense of divine blessing upon the empire.

For the succeeding emperors, it was a way to connect themselves to a divine lineage, further legitimizing their rule.

However, the relationship between emperors and divinity was not always straightforward.

While some emperors, like Hadrian, were genuinely pious and saw their role as a sacred duty, others, like Caligula, took the association to extremes, demanding to be worshipped as living gods.

Such actions often led to tensions, as they challenged traditional Roman religious sensibilities.

Bonus Tip: Keep the Common People Happy

The streets of ancient Rome teemed with life, and among its bustling crowds, the Roman mob emerged as a force to be reckoned with.

While the Senate and the military often dominated political narratives, the collective voice of the Roman populace held its own unique power.

This was especially true in the city of Rome itself, where the concentration of citizens and the proximity to the epicenter of power made the mob's sentiments hard to ignore.

Emperors and politicians were acutely aware of the need to keep the Roman mob content.

The age-old policy of "bread and circuses" was a testament to this understanding.

By providing free grain distributions and grand spectacles in the Colosseum and other venues, leaders aimed to appease and distract the masses.

These events were not just entertainment; they were political tools, ensuring that the populace remained fed and favorably disposed towards the ruling elite.

The influence of the mob was also evident in the political arena. During the Republic, popular assemblies, where citizens gathered to vote on laws and elect officials, were central to the governance process.

While the direct political power of these assemblies diminished during the Empire, the spirit of public participation and the need to gauge and respond to the mob's sentiments persisted.

What to do once you've gained power

The path to becoming and remaining a Roman emperor was fraught with challenges and pitfalls.

While the allure of the imperial title was undeniable, with its unparalleled power and prestige, the position also came with immense pressures and dangers.

The very factors that could elevate an individual to the throne could also lead to their downfall.

One of the primary challenges was the ever-present threat of assassination. The history of the Roman Empire is punctuated with tales of emperors meeting untimely ends at the hands of disgruntled senators, ambitious rivals, or even members of their own household.

The Praetorian Guard, established to protect the emperor, was ironically responsible for the assassination or overthrow of several of them.

Emperors had to constantly be on guard, ensuring the loyalty of those closest to them and navigating the treacherous waters of palace intrigue.

Another significant challenge was managing the vast and diverse Roman Empire.

With territories spanning three continents, the empire was a mosaic of cultures, languages, and interests.

Balancing the needs and aspirations of these diverse provinces while ensuring the smooth flow of taxes and resources to the heart of the empire was a monumental task.

Emperors had to contend with local uprisings, external threats, and the logistical challenges of governing such a vast domain.

Economic pressures also posed challenges. Ensuring the steady supply of grain to feed the populace of Rome, managing the empire's finances, and overseeing vast infrastructure projects required astute economic management.

Economic downturns or mismanagement could lead to unrest, challenging the emperor's rule.

Furthermore, the very nature of the imperial succession was a pitfall in itself.

Without a fixed system in place, the transition between emperors was often a period of uncertainty and potential conflict.

Rivals, backed by different factions of the military or the elite, could plunge the empire into civil war, vying for the throne.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.