What burial archaeology reveals about ancient civilizations

Today, not many people choose to visit graveyards. However, throughout human history, the burial of people was an incredibly important part of many civilizations.

As a result, archaeologists have unearthed fascinating burial sites, scattered across almost all continents, which reveal how people honored their dead.

These sites often include precious grave goods that reflect the deceased person’s status and profession in life. With each new discovery, we learn about the wide range of beliefs that humans have held about what happens after death.

The history of human burials

Burial practices have evolved significantly over millennia. In ancient Egypt, as early as 3000 BCE, elaborate tombs were constructed for pharaohs, which focused on their divine status.

Such tombs, which include the Great Pyramids, contained valuable goods meant to accompany the deceased into the afterlife.

Decorated with intricate designs, these grave goods help preserve the Egyptians' complex beliefs about death and immortality.

By contrast, the Romans, who dominated much of Europe from 27 BCE to 476 CE, practiced both cremation and inhumation (burying).

Early in their history, cremation was more common, with ashes from the cremation placed in urns for burial.

However, by the second century CE, inhumation became more common. This resulted in the construction of elaborate underground catacombs.

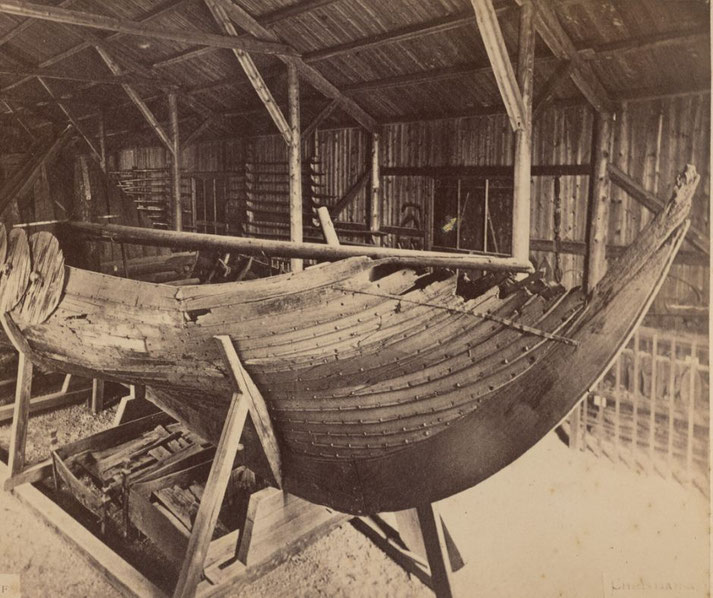

In Northern Europe, the Viking Age (circa 793–1066 CE) introduced ship burials, where significant individuals were interred with their ships and personal belongings.

It is believed that this was done because of the Vikings' particular belief about the journey they need to take in order to get to the afterlife.

Among the most famous is the Oseberg Ship, discovered in Norway in 1904, which contained the remains of two women and numerous grave goods.

On the other side of the globe, in ancient China, burial practices could vary greatly between dynasties.

During the Shang Dynasty (circa 1600–1046 BCE), human and animal sacrifices accompanied elite burials.

By the time of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), tombs became more intricate and often resembling underground palaces.

These tombs were filled with terracotta figurines, known as mingqi, which were designed to represent the servants and soldiers who were meant to serve the deceased in the afterlife.

Indigenous cultures in the Americas also had unique burial practices. The Mississippian culture (circa 800–1600 CE) in North America built large earthen mounds that served as burial sites, as well as ceremonial centers for the living.

These mounds, such as those at Cahokia in present-day Illinois, contained artifacts that suggest complex trade networks and social structures.

As you can see, burial practices were as diverse as the human societies that developed them.

Regardless of the exact system, they all had a way of trying to deal with death and honored their deceased.

What are the types of ancient human burials?

As we can now appreciate, individual burial practices can vary widely across different cultures, since they exhibit a wide variety of methods and traditions.

One common type of human remains is inhumation, where the body is buried directly in the ground.

Cremation was another widespread practice. This involves burning the body and placing the ashes in an urn or scattering them in a significant location.

There is also something called a ‘secondary burial’, where the body is initially buried or left to decompose, and the remains are later reburied.

This practice often involves collecting bones and placing them in ossuaries, which are containers or rooms designed to hold skeletal remains.

In some cultures, secondary burials were part of complex funerary rituals that reflected ongoing relationships between the living and the dead.

Sometimes, mass graves have been found, which were often associated with times of war, plague, or disaster.

These graves contain multiple individuals buried together, sometimes hastily and without individual markers.

As a consequence, archaeologists study mass graves to understand the circumstances surrounding these events and the impact on affected communities.

Perhaps the most well-known kind of ancient burials were those done in tombs and mausoleums.

These are monumental structures designed to house the dead, which were often built for royalty or the elite.

The Great Pyramids of Egypt are perhaps the most iconic examples. But, in medieval Europe, they also built elaborate mausoleums and crypts, and were frequently constructed within churches and cathedrals.

Finally, there are ‘simple graves’: often found in more modern contexts. This involved basic interment without elaborate structures or goods.

Despite the lack of objects in these burials, they also provide important information about everyday individuals who lived outside the elite classes.

By studying simple graves, archaeologists can learn about the common people's lives, health, and burial customs, since they can reflect the broader societal and economic conditions of the time.

How do archaeologists excavate graves?

Burial archaeology employs various methodologies to uncover and understand ancient burial practices.

One fundamental technique is excavation, which involves the systematic removal of soil and other materials to reveal burial sites.

During excavation, archaeologists meticulously document the context and position of artifacts and human remains.

By so doing, they attempt to ensure that valuable information about the burial's original state is preserved.

Relative dating techniques, such as stratigraphy, help archaeologists determine the chronological order of burials.

Stratigraphy involves analyzing the layers of soil deposition, with deeper layers typically representing older deposits.

In addition to stratigraphy, typology is used to classify artifacts based on their characteristics and styles.

These methods allow researchers to establish a sequence of events and cultural changes over time.

Absolute dating methods, like radiocarbon dating, can also provide more precise age estimates for organic materials found in burials.

Radiocarbon dating measures the decay of carbon-14 isotopes in organic remains, such as bones and wooden artifacts.

With this technique, archaeologists can determine the age of these materials within a few decades.

Dendrochronology, another absolute dating method, uses tree-ring analysis to date wooden objects accurately.

Other analytical techniques, including osteoarchaeology, focus on studying human skeletal remains to glean information about the deceased.

Osteoarchaeologists examine bones to determine age, sex, health, and cause of death.

This can be combined with other advanced methods like isotope analysis, through which they can also infer details about diet and migration patterns.

As a result, they can begin to reconstruct the life histories of individuals and even broader population trends.

More recently, technologies such as ground-penetrating radar (GPR), allow archaeologists to locate and map burial sites without having to disturb the soil.

GPR works by sending radar pulses into the ground and detecting the reflected signals. This can reveal subsurface structures.

As a result, this non-invasive method is particularly useful in identifying unmarked graves and burial mounds, which helps archaeologists to plan excavations more precisely in order to avoid unnecessary disturbance of the sites.

Finally, they can draw on interdisciplinary collaboration to enhance the study of their finds.

Nowadays, they can call on forensic scientists, bioarchaeologists, and geologists to contribute their expertise to analyze burial contexts more comprehensively.

For instance, forensic techniques can be applied to identify trauma or disease in skeletal remains.

Why do humans bury their dead?

Humans are a unique species in that we place a great deal of emphasis on commemorating and remembering those who have died.

This goes some way to explaining the different kinds of burial practices, since they hold different significance to different social structures.

For many, they viewed burial practices as a way to honor the deceased and preserve their memory.

In some cultures, wealthy families often constructed grand mausoleums and elaborate tombs to house the remains of multiple generations.

These burial monuments were also meant to be public displays to the broader community.

This is similar to the idea of honoring your ancestors in many cultures. In cultures like the Chinese, ancestor worship played a crucial role in family life.

People were expected to maintain the tombs of their families and to conduct annual rituals to honor them.

One feature that appears in many cultures is the attempt to preserve the image of the dead person.

In medieval Europe, burials often included detailed effigies and inscriptions, ensuring that the deceased would be remembered and prayed for.

The Egyptians as well, took the time to construct death masks that represented the face of the dead.

Similar practices can be found in almost every continent around the world.

Famous burials sites around the world

Several notable burial sites around the world have revealed fascinating insights into ancient civilizations.

The Valley of the Kings in Egypt, used from the 16th to the 11th century BCE, served as the final resting place for pharaohs and powerful nobles.

Among its most famous tombs is that of Tutankhamun, discovered in 1922 by Howard Carter, with its rich treasures and well-preserved artifacts.

In England, Sutton Hoo is a significant burial site dating to the early 7th century. It contained an Anglo-Saxon ship burial, believed to be the grave of King Raedwald.

The site, which was discovered in 1939, included a wealth of grave goods such as a helmet, weapons, and gold ornaments.

The Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor in China, built around 210 BCE, is another remarkable site.

Emperor Qin Shi Huang was buried with an entire terracotta army intended to protect him in the afterlife.

With thousands of life-sized figures, the site represents the emperor's power and the importance of the afterlife in Chinese culture.

Discovered in 1974, the terracotta army continues to be a major archaeological and tourist attraction.

In Peru, the tomb of the Lord of Sipán, dating to around 750 CE, provides valuable insights into the Moche civilization.

Discovered in 1987, the tomb contained elaborate jewelry, ceramics, and other artifacts.

These items highlighted the wealth and craftsmanship of the Moche people. As a result of such rich finds, archaeologists have been able to reconstruct aspects of Moche social and political life.

In Greece, the royal tombs at Vergina, discovered in 1977, are believed to include the burial site of Philip II, father of Alexander the Great.

These tombs contained gold artifacts, weapons, and ceremonial items, reflecting the wealth and power of Macedonian kings.

Through these discoveries, the history and influence of the Macedonian empire became clearer.

The challenges of burial archaeology

Burial archaeology, as a field of study, is incredibly difficult. The most pressing problem is always about the preservation of fragile organic materials like wood and textiles, since they degrade quickly over time.

In wet or acidic soils, even bones can dissolve, which leave few traces behind.

When this happens, archaeologists sometimes struggle to piece together complete burial contexts.

Additionally, there are ethical considerations to consider. Descendant communities often have strong ties to particular burial sites and may oppose excavations for emotional reasons.

For example, Native American groups in the United States advocate for the protection and repatriation of ancestral remains under laws like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

By respecting concerns like this, archaeologists must balance scientific inquiry with cultural sensitivity.

What many people don’t often realize is that there are complex legal aspects when working on burial sites. Many countries have strict regulations regarding the excavation of human remains.

As a result, permits and legal approvals can be difficult to obtain, especially in regions with complex bureaucracies.

This has become even more difficult when discussions arise about the repatriation of artifacts and human remains.

Over the last few centuries, archaeologists have removed human remains from their countries of origin in order to store them in museums around the world.

For example, many Egyptian artifacts are housed in Britain. As a result, countries are reluctant to allow archaeologists to work on burial sites if they fear that precious remains will be taken out of the country.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.