Rome's addiction to deadly speed: The thrills and spills of ancient chariot racing

In the centre of ancient Rome, beneath the relentless sun, the deafening roar of a crowd echoed across the sprawling expanse of the Circus Maximus.

Chariots, drawn by frothing steeds, raced perilously close, their wheels nearly touching, as they hurtled down the track.

Charioteers, with clenched jaws and white-knuckled grips, navigated these lethal machines, their lives hanging by a thread, all for glory, honor, and the deafening approval of the masses.

But what drove these men to risk everything in the high-stakes world of Roman chariot racing?

How did this spectacle come to captivate an empire, intertwining with its politics, culture, and very identity?

The origins of chariot racing in Rome

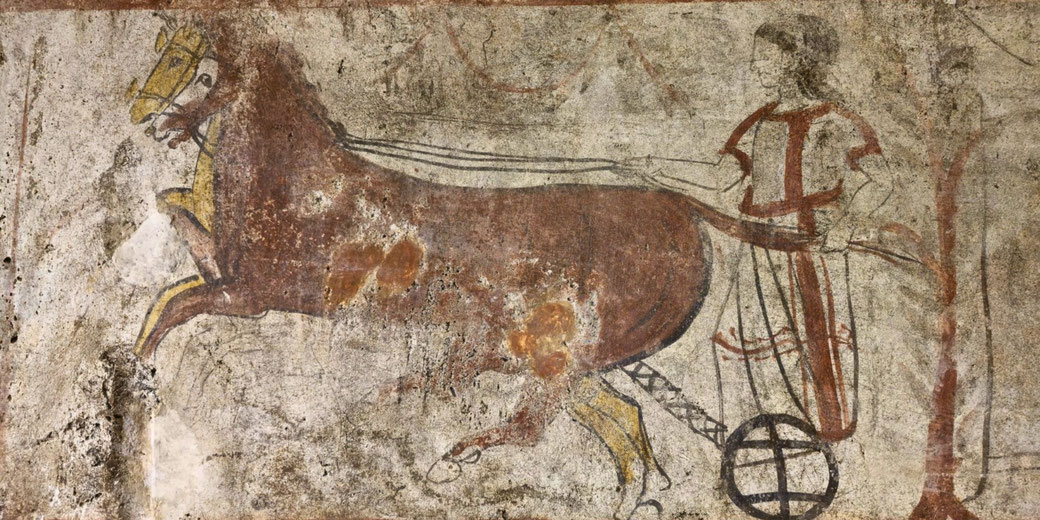

The Etruscans, who once dominated the Italian peninsula before the rise of Rome, are often credited with introducing the Romans to the thrilling sport of chariot racing.

As spectators to the grand Etruscan festivals, the early Romans marveled at the sight of speeding chariots, a testament to both athletic prowess and spiritual significance.

Inspired by what they witnessed, the Romans began integrating these races into their own religious festivals and celebrations.

The races often commenced with grand processions, accompanied by religious ceremonies dedicated to the gods.

The earliest races in Rome were deeply entwined with the worship of deities such as Mars, the god of war, and Consus, the god of harvest and grain.

These ceremonies, held at the base of the Palatine Hill, would eventually pave the way for the establishment of the Circus Maximus during the reign of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus (r. 616-579 BCE), which became Rome's most iconic racing venue.

As the Roman Republic began its expansion, absorbing various cultures and traditions, chariot racing evolved, borrowing and adapting elements from the broader Mediterranean world.

The influence of Greek athletic traditions and the infusion of Eastern elements from places like Egypt played a role in shaping the sport.

It was in this melting pot of cultures that chariot racing began its ascent to the status of the most celebrated sport in ancient Rome.

Where were chariot races held?

Nestled between the Palatine and Aventine hills in the heart of Rome, the Circus Maximus was the most important venue for these events.

Once a humble racing track, over centuries and under the directives of various emperors, it evolved into an architectural marvel that could house around 250,000 spectators.

Longer than most modern-day stadiums at approximately 621 meters and designed with an elongated U-shape, the Circus Maximus offered a challenging and exciting track for charioteers, complete with treacherous turns around the spina, the central barrier.

The spina was adorned with obelisks and statues, adding a touch of imperial splendor to the race's adrenaline rush.

While the Circus Maximus was undeniably the jewel in the crown, Rome's vast landscape was dotted with other circuses, each with its own unique history and importance.

The Circus of Maxentius, built along the Appian Way, stood as a symbol of the sport's reach beyond the city's boundaries.

This venue, though less frequented than its counterparts within Rome, offered a glimpse into the enduring appeal of chariot racing among the empire's elite.

But the influence of Roman chariot racing extended to the eastern fringes of the empire, in the grand Hippodrome of Constantinople.

Although not originally Roman, the Byzantine Empire's capital embraced the sport with an ardor reminiscent of Rome at its peak.

The Hippodrome, central to Constantinopolitan public life, became a melting pot of politics, sport, and societal expressions, much like the Circus Maximus had been for Rome.

The most famous chariot racing teams

Initially, there were two primary teams you could cheer for, which were called 'factions': the Reds (Russata) and the Whites (Albata).

As the sport's popularity soared, two more factions were introduced: the Blues (Veneta) and the Greens (Prasina).

Each faction was distinguished by its colors, but over time, they evolved into potent symbols of identity, with supporters displaying an unwavering and often fierce loyalty.

The Blues and the Greens, in particular, rose to prominence and became the most influential factions in the later stages of the Roman Empire.

While they began as sporting factions, their influence spilled over into politics, culture, and street life.

Emperors had their preferences, often aligning themselves with one of these dominant factions, further intertwining chariot racing with Roman political affairs.

The rivalry between the two was intense, leading to frequent street brawls and even riots.

One of the most infamous incidents was the Nika riots of AD 532 in Constantinople, where supporters of the Blues and Greens united momentarily in rebellion against Emperor Justinian, almost toppling his reign.

How to become a chariot racer in ancient Rome

Behind the colorful banners of these factions were the charioteers – the superstars of their time.

Many began their careers as slaves or freedmen but had the potential to rise to immense fame and fortune through their skills and daring on the track.

These charioteers, wrapped in the colors of their factions, became household names, eliciting cheers and sometimes jeers from the packed stands of the circus.

Their lives were paradoxical: on the one hand, they basked in the glory of their victories, earned vast fortunes, and even found their way into romantic and heroic tales.

On the other, they faced immense risks every time they stepped onto the track, with many races ending in injury or death. Estimates suggest dozens of charioteers died each year.

One such iconic figure was Gaius Appuleius Diocles, a charioteer who raced for the Reds, Whites and Greens during his time.

His long career spanned over two decades, and his earnings were astronomical, surpassing the wealth of some of Rome's most elite. An inscription explicitly records his total career earnings as 35,863,120 sesterces, equivalent to $15 billion dollars.

Diocles, like many charioteers of his time, became a symbol of hope, representing the possibility of rising from humble beginnings to unparalleled stardom.

What happened during a chariot race?

A typical race would see twelve chariots competing, each trying to complete seven laps around the spina of the circus.

While this may sound straightforward, the complexity and strategy involved were paramount.

The quadriga, a chariot pulled by four horses abreast, was the most common configuration, demanding the charioteer manage the power and temperaments of four individual steeds.

This required an intricate balance: pushing for speed while ensuring the horses maintained stamina throughout the race.

The charioteer's whip and voice became tools of both encouragement and control, as he communicated with his horses.

The turns at each end of the spina, marked by the metae (turning posts), were the most perilous points in the race.

Here, chariots could easily crash into each other or the barrier, resulting in dramatic and often deadly wrecks.

Strategy became crucial, with charioteers deciding between taking the riskier inner track, which was shorter but had a higher chance of collisions, or the outer, longer but safer route.

The danger was part of the allure. Spectators held their breath as chariots navigated these turns, often leading to the most memorable and talked-about moments of the race.

Beyond the physical challenges of the race, there was an intense psychological game at play.

Charioteers had to read their competitors, anticipate moves, and adjust their strategies on the fly.

Some might form temporary alliances, teaming up against a particularly formidable charioteer, only to then compete fiercely against each other in the final laps.

Others might employ deceptive tactics, feigning weakness only to unleash a burst of speed at the last moment.

The culmination of a race was an event in itself. The victor would be lauded as a hero as they were awarded a palm branch and a wreath of laurel or another plant sacred to the games' presiding deity.

But more than the tangible rewards, it was the glory, the adulation of the masses, and the chance to be immortalized in song and story that drove these charioteers to risk their lives in the frenzied circuits of the circus.

How the rich and poor were treated differently

The very nature of the Circus Maximus, with its tiered seating, illustrated the societal stratification of Rome.

Senators and elite aristocrats occupied the best seats, ensuring they were both visible and comfortable, while the general populace filled the upper tiers.

Yet, for all these demarcations, the circus was one of the few places where the entire spectrum of Roman society — from the emperor to the commoner — gathered together.

This shared experience, a rare moment of societal unity, acted as a pressure valve, allowing the masses a temporary respite from the challenges of their daily lives.

Emperors, astutely recognizing the importance of 'bread and circuses' (panem et circenses) as a means to placate and control the populace, invested heavily in the games.

By sponsoring grand races and ensuring the populace was entertained, they diverted attention from political issues, economic downturns, or external threats.

However, this strategy was a double-edged sword. While successful games could bolster an emperor's popularity, any perceived mismanagement could incite the crowd's wrath.

The circus became both a stage for imperial propaganda and a potential site for political dissent.

The factions further complicated this socio-political tapestry. As the factions, particularly the Blues and the Greens, grew in power and influence, they transformed from mere sporting teams to entities representing broader societal concerns.

They became deeply entwined with political intrigues, with different emperors and senators aligning with or against certain factions based on the shifting nature of Roman politics.

Factional riots, often erupting from chariot racing disputes, were not just expressions of sports fanaticism but reflections of deeper societal tensions.

Why chariot racing fell from popularity

Economically, maintaining the grandeur of chariot racing became increasingly untenable.

The expenses involved in organizing the races, from maintaining the circuses and stadia to the breeding and training of high-quality horses, became burdensome.

As the western Roman Empire grappled with economic downturns, external threats, and internal discord, the allocation of resources to chariot racing began to wane.

Sponsorship from the elite, which had once ensured the sport's opulence, became sporadic, reflecting the empire's changing economic realities.

Politically, the rise of Christianity played a role in the sport's decline. Early Christian leaders, viewing the games as pagan spectacles steeped in decadence and immorality, began to oppose them.

Emperors, once the grand patrons of chariot racing, especially after the Constantinian shift to Christianity, became ambivalent and sometimes even hostile to the games.

Theodosius I, in the late 4th century AD, marked a significant blow by banning many pagan festivals and games, although chariot racing, due to its immense popularity, managed to survive for a while longer.

Despite these challenges, chariot racing continued in the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantium.

The Hippodrome of Constantinople continued to host chariot races long after they had dwindled in the west.

However, even here, the sport's glory days were numbered. The Nika Riots of AD 532, a violent and massive revolt partially rooted in chariot racing rivalries, showcased the potential dangers of the sport's factionalism.

Although Justinian I rebuilt the Hippodrome and the sport continued, its influence gradually decreased, eventually becoming a shadow of its former self by the end of the first millennium AD.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.