Why did ancient Egyptian pharaohs marry their sisters?

Ancient Egypt was truly a strange place, whose beliefs and practises were vastly different to our own. One ancient Egyptian cultural tradition stands out particularly odd: the custom of pharaohs marrying their sisters.

At first glance, this practice might seem unusual, even taboo, to modern sensibilities. However, in the context of ancient Egyptian culture, it was deeply rooted in religious beliefs, political strategies, and societal norms.

Understanding Egyptian religious beliefs

In ancient Egypt, religion was not a mere aspect of life; it was the very essence that permeated every facet of existence.

The pharaohs, as both rulers and divine representatives on Earth, were central figures in this religious landscape.

Their actions, choices, and even personal relationships were seen through the lens of religious significance, and their marriages were no exception.

The pantheon of Egyptian gods provided a blueprint for the pharaohs. Among the myriad tales of deities, the story of Osiris and Isis stood out.

This god and goddess were not only only brother and sister, but also devoted spouses.

Their love was emblematic of unity, strength, and divine purpose.

Osiris, the god of the afterlife, and Isis, the goddess of magic and motherhood, together represented the cyclical nature of life and death, rebirth, and regeneration.

Their union was a testament to the idea that love and partnership could transcend even the boundaries set by nature.

For the pharaohs, emulating this divine relationship was a way to align themselves with the gods, drawing parallels between their earthly reign and the eternal rule of the deities.

Furthermore, the concept of Ma'at, the ancient Egyptian principle of truth, balance, and cosmic order, played a pivotal role in the pharaohs' decision to marry their sisters.

By keeping the royal bloodline pure and undiluted, they believed they were upholding Ma'at, ensuring that the cosmic balance remained undisturbed.

Any deviation from this practice could potentially invite chaos, disrupting the equilibrium between the realms of gods and men.

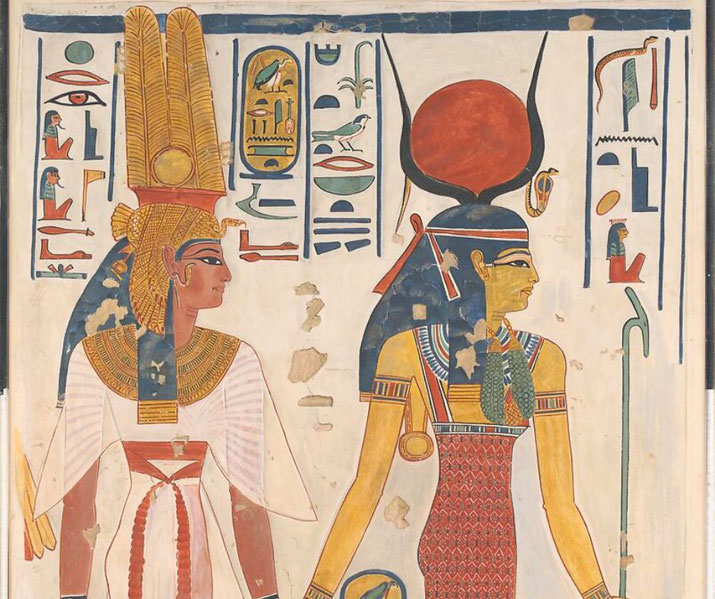

Additionally, temples, the epicenters of religious activity in ancient Egypt, often depicted pharaohs and their queens in divine forms, further solidifying the notion of their god-like status.

These depictions were not mere artistic expressions; they were visual affirmations of the pharaohs' divine lineage and their sacred duty to uphold the traditions set by the gods.

Political motivations for brother-sister marriages

The pharaoh's position, though divine in nature, was not immune to challenges, both from within the royal family and from external contenders.

Marrying a sister, in this context, was a shrewd political maneuver with multifaceted benefits.

First and foremost, these marriages ensured a clear and uncontested line of succession.

In a world where power struggles and claims to the throne could lead to civil unrest or even outright war, keeping the lineage within the immediate family minimized potential disputes.

A son born from a union between the pharaoh and his sister was seen as having the purest royal blood, making his claim to the throne indisputable.

Additionally, marrying within the family consolidated power. By preventing alliances with other influential families, the pharaoh ensured that the seat of power remained firmly within his immediate lineage.

External marriages could bring about alliances, but they also introduced the risk of divided loyalties or the potential for the external family to amass enough influence to challenge the throne.

A sister-queen, having grown up in the same environment and sharing the same upbringing, was more likely to be a trusted ally, ensuring that the pharaoh's decrees and policies were supported and executed without contention.

Furthermore, these sibling marriages were a public display of the pharaoh's commitment to tradition and stability.

In a society where change could be viewed with suspicion, especially when it pertained to the divine rulership, adhering to established practices reinforced the pharaoh's legitimacy.

It sent a clear message to the populace and potential adversaries: the pharaoh was not only the chosen one of the gods but also a guardian of time-honored traditions.

What about the common people in ancient Egypt?

The pharaohs, as divine rulers, usually set the tone for many societal norms, and their practices were often emulated or revered by the general populace.

To the average Egyptian, the pharaohs' marriages to their sisters were perceived as a divine mandate, a reflection of the unions of gods and goddesses in the celestial realm.

However, when it came to the common people, sibling marriages were not the norm.

While close-knit family structures and marriages within extended families were common, direct sibling unions were rare and not encouraged.

The distinction between royal and common practices was clear, and it was understood that certain privileges and responsibilities were exclusive to the pharaoh due to his divine status.

Culturally, ancient Egyptians placed great emphasis on lineage, heritage, and familial ties.

Families were the cornerstone of society, and practices that strengthened family bonds were encouraged.

The genetic and health impacts on the royal family

From a genetic standpoint, offspring resulting from close relative unions have a higher risk of inheriting recessive genetic disorders.

This is because close relatives are more likely to carry the same recessive genes, and when both parents pass on a copy of such a gene, the child can manifest the associated disorder.

Over generations, if intermarriage continues, the probability of these genetic disorders surfacing becomes even more pronounced.

Historical records and archaeological findings suggest that some members of the Egyptian royal family did exhibit signs of health issues.

For instance, King Tutankhamun, one of the most famous pharaohs, is believed to have had multiple health problems.

Modern analyses of his remains suggest conditions like a cleft palate, clubfoot, and other skeletal anomalies.

Genetic studies have indicated that his parents were likely siblings, which could have contributed to his health issues.

Similarly, other mummies from the royal lineage have shown signs of diseases and deformities, which might be attributed to the practice of intermarriage.

Culturally, the ancient Egyptians were aware of the concept of heredity, as evident from their emphasis on lineage and bloodlines.

However, their understanding of genetics and hereditary diseases was not as advanced as today's knowledge.

It's likely that the pharaohs, motivated by their religious and political beliefs, did not fully grasp the potential health implications of sibling marriages.

Or, even if they did recognize certain health issues within their lineage, the religious and political imperatives might have outweighed these concerns.

Famous examples of brother-sister marriages

Arguably the most famous example, as mentioned above, is King Tutankhamun, often referred to as King Tut.

His short-lived reign and the subsequent discovery of his nearly intact tomb in the Valley of the Kings have made him an iconic figure in Egyptology. G

Genetic studies on his mummy have revealed that he was the offspring of a brother-sister union, likely between the pharaoh Akhenaten and one of his sisters.

King Tut himself married his half-sister, Ankhesenamun, and the couple had two daughters, both of whom were stillborn, possibly due to genetic complications arising from their close familial relationship.

Another notable example is Cleopatra VII, the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt.

The Ptolemies, a Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great, were known for intermarrying within the family to keep the bloodline pure and maintain their grip on power.

Cleopatra, in keeping with this tradition, married both of her younger brothers at different times: Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV.

Her relationships with these siblings, especially Ptolemy XIII, were fraught with political intrigue and power struggles, culminating in civil wars and her eventual sole rulership.

The earlier pharaohs of the Old Kingdom also provide instances of sibling marriages.

Pharaoh Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza, is believed to have married his half-sister, Meritites.

Their son, Pharaoh Khafre, who commissioned the construction of the second-largest pyramid at Giza and the Great Sphinx, also married his sister, Khamerernebty I.

Did other ancient cultures do the same thing?

In ancient Persia, particularly during the Achaemenid dynasty, royal sibling marriages were practiced.

Much like the Egyptians, the Persians believed that such unions preserved the purity of the royal bloodline.

The divine status attributed to the Persian kings, seen as representatives of the god Ahura Mazda on Earth, further reinforced the practice.

Xerxes, one of the most famous Achaemenid kings, married his sister, Amestris, and their union was both politically strategic and religiously significant.

The Inca civilization, which flourished in South America, also saw sibling marriages among its royalty.

The Sapa Inca, the emperor, often married his full sister to maintain the sanctity and purity of the royal bloodline.

In the Incan worldview, the royal family was descended from the Sun God, Inti, and marrying within the family was a way to preserve this divine lineage.

The practice was so entrenched that commoners in the Inca Empire accepted it without question, viewing the royal family as distinct and bound by different rules.

In contrast, while other ancient civilizations like Rome and Greece recognized the political advantages of marriage alliances, direct sibling marriages were rare and often viewed with disdain.

Instead, these cultures practiced other forms of inter-familial marriages, such as unions between cousins.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.