Why did the ancient Egyptians build obelisks?

Egyptian obelisks, those monumental tapering columns crafted from stone, are among the most iconic symbols of ancient Egyptian civilization.

The name 'obelisk' itself comes from the Greek 'obeliskos', meaning a pointed pillar, but in ancient Egypt, they were known as 'tekhenu', which translates to 'piercing the skies'.

Typically carved from a single piece of stone, obelisks were engineering marvels of their time.

Their creation involved not only the meticulous art of stone carving but also the complex logistics of transporting these massive structures from quarry sites to their final destinations, often miles away.

The mystical reason for their construction

These slender, tapering monuments, often towering at impressive heights, were hewn from single blocks of stone, primarily red granite sourced from the quarries of Aswan.

The Egyptians believed that the obelisks, reaching towards the heavens, acted as a conduit for divine energy, channeling the power of the sun god into the temples and cities where they stood.

The choice of material was deliberate; the red granite was not only durable but also symbolically linked to the sun due to its color, reflecting the belief in the obelisk's connection to the sun god, Ra.

The shape of the obelisk, a pyramidion or small pyramid atop a long, slender shaft, was deeply symbolic.

This form was believed to act as a petrified ray of the sun. The Egyptians saw the obelisks as a physical representation of the sun's power, vital for life and prosperity.

The pyramidion was often covered in gold or electrum (a mix of gold and silver), materials revered for their ability to reflect the sun's rays.

This capstone, glittering in the sunlight, was a visual representation of the sun's power touching the earth.

The hieroglyphic inscriptions on obelisks played a significant role in their symbolism.

These inscriptions were typically praises to the gods, especially the sun god Ra, and commemorated the achievements of the pharaohs who commissioned them.

The texts served both a religious purpose and a political one, immortalizing the pharaoh's name and deeds.

The inscriptions, usually on all four sides, were meticulously carved and often painted, making them visible and legible from a distance.

The ancient Egyptians were skilled astronomers, and the positioning of the obelisks was carefully considered in relation to the movement of the sun.

The obelisks' shadows would move throughout the day, and it is believed that they could have been used to mark significant solar events, such as solstices and equinoxes.

These observations were crucial in maintaining the Egyptian calendar, which was closely linked to agricultural cycles and religious festivals.

Obelisks were strategically placed at temple entrances or near important religious buildings, creating a visual pathway leading to the sacred space.

This placement was symbolic, suggesting that the journey towards the gods was guided by the divine light of the sun, as represented by the obelisks.

In pairs, they also symbolized the duality found in Egyptian beliefs, such as the balance between Upper and Lower Egypt or the harmonious union of the divine masculine and feminine.

The incredible way they were made

These monumental structures, carved from single pieces of stone, required precise planning and execution.

The process began in the quarries, where workers would identify a suitable piece of granite.

They then chiseled around the desired block, creating a trench and isolating it from the bedrock.

The isolation of the stone was achieved using a series of dolerite balls, harder than granite, to pound and shape the desired block.

Once the block was separated, the painstaking task of shaping the obelisk began.

Craftsmen used a combination of tools, such as chisels and hammers, to carve the stone into the iconic obelisk shape.

This process required immense precision, as any mistake could render the entire block useless.

The hieroglyphic inscriptions were then added, carved deep into the stone to endure through time.

Transporting these massive structures from the quarry to their final destination was perhaps the most challenging part of the process.

The ancient Egyptians likely used a combination of sledges and rollers, along with the power of human labor, to move the obelisks.

The path from the quarry to the Nile River was prepared with a smooth, lubricated track to ease the movement.

The obelisks were then carefully loaded onto barges for transport along the Nile to their intended site.

This journey could take many months and required careful navigation to avoid damaging the stone.

Upon arrival at the building site, the obelisk had to be erected, a task that was as challenging as its carving and transportation.

This feat was likely achieved using a combination of ramps, ropes, and counterweights.

Workers would gradually tilt the obelisk upright while controlling its ascent with ropes and guiding it into a pre-prepared pit or base.

The precision required for this task was immense, as the obelisk needed to be perfectly vertical to achieve both its aesthetic and symbolic purposes.

The most famous Egyptian obelisks

One of the earliest known obelisks was erected by Senusret I of the Twelfth Dynasty, found at Heliopolis, a major religious center. This obelisk showcased his power and devotion to the sun god Ra.

Thutmose III, one of Egypt’s greatest warrior pharaohs, commissioned several obelisks.

The Lateran Obelisk, originally at Karnak and now in Rome, stands as a testament to his military campaigns and religious dedication.

His reign was a period of great architectural and artistic achievements, and his obelisks were a significant part of this legacy.

Queen Hatshepsut, a formidable female pharaoh, also commissioned obelisks.

The twin obelisks she erected at Karnak were among the tallest ever built in ancient Egypt.

One still stands today, a soaring monument reaching about 97 feet high.

These obelisks were not just expressions of her power but also her unique position as a female ruler in a male-dominated society.

They bear inscriptions praising Amun and detailing her divine birth, reinforcing her legitimacy as pharaoh.

Ramses II, known as Ramses the Great, was another prolific builder of obelisks.

His reign is marked by numerous construction projects, including the erection of obelisks.

The Ramesseum, his mortuary temple, once housed one of his many obelisks.

These structures served to emphasize his strength and the longevity of his reign, which spanned over six decades.

Obelisks were also commissioned by later pharaohs such as Psammetichus II, who erected an obelisk in Heliopolis, and Cleopatra VII, the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, who had a pair of obelisks made.

While often associated with Cleopatra, these obelisks were actually erected more than a decade after her death.

They were moved to Alexandria and later known as Cleopatra's Needles, one of which now resides in New York's Central Park and the other on the Victoria Embankment in London.

Why are Egyptian obelisks located around the world?

The relocation of Egyptian obelisks to various parts of the world has sparked controversies and debates around cultural heritage and repatriation.

These obelisks, originally erected as symbols of divine and royal power in ancient Egypt, have become focal points of discussions about the ownership and stewardship of cultural artifacts.

The 19th and early 20th centuries saw European powers and the United States acquiring Egyptian obelisks, often as symbols of imperial power or as diplomatic gifts.

For instance, the obelisks known as Cleopatra's Needles in London, Paris, and New York were transported from Egypt during this period, an era marked by colonial expansion and a keen interest in ancient cultures.

One of the most famous is the Lateran Obelisk in Karnak. Originally erected by Pharaoh Thutmose III, it is the largest standing ancient Egyptian obelisk in the world, and it currently resides in the Lateran Palace in Rome.

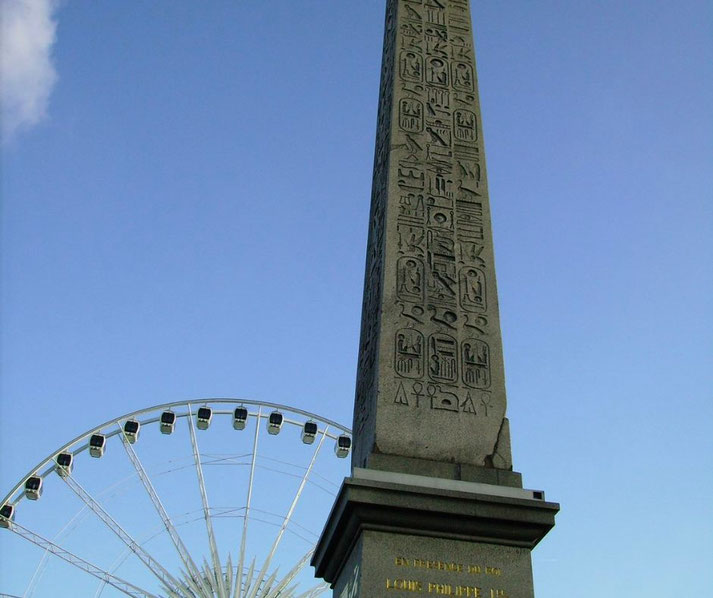

Another notable example is the Luxor Obelisk, which once paired with its twin (still in Luxor, Egypt) at the entrance to the Luxor Temple.

The Luxor Obelisk now stands majestically in the Place de la Concorde in Paris, a gift from Egypt to France in the 19th century.

In London, the Cleopatra's Needle, located on the Victoria Embankment near the River Thames, is another example of an Egyptian obelisk.

It was originally erected in Heliopolis before being moved to Alexandria and eventually to London in the late 19th century.

Its twin is found in New York City's Central Park, often referred to by the same name, Cleopatra's Needle, despite having no historical connection to Queen Cleopatra.

In Istanbul, the Obelisk of Theodosius, originally from the Karnak Temple, is prominently displayed in the Hippodrome.

Although it is much shorter now than its original height, it still stands as a fascinating example of Egyptian craftsmanship.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.