The ‘god’s wife of Amun’: The powerful Egyptian women who married a god

Few titles in ancient Egypt carried the same weight as the god's wife of Amun, a position that granted immense power to the women who held it.

In the shadowy halls of Karnak, she performed mysterious sacred rites that were thought to uphold the tenuous balance between the gods and the people.

But how did someone become the ‘wife of Amun’?

What was the ‘god’s wife of Amun’?

The first reference to the title of god’s wife of Amun emerged during the Middle Kingdom, around 2000 BCE, as a religious role initially tied to the powerful cult of Amun.

The god Amun was one of the most important gods in the Egyptian pantheon and his priests became a significant force within the state, both religiously and politically.

The women who held the title of god’s wife of Amun did not marry the god in a literal sense.

Instead, their role symbolized a spiritual union with Amun, designed to elevate the god’s wife to a divine status within the temple hierarchy.

In ancient Egyptian belief, the gods had relationships with mortals, and the god’s wife was believed to serve Amun in a manner similar to that of a queen consort.

As the highest-ranking priestess of the Amun cult, she conducted sacred rituals, which were integral to ensuring the god's continued favor toward the kingdom.

These rituals, such as the daily ‘opening of the mouth’ ceremony, involved offerings of food, drink, and incense to the statues of Amun.

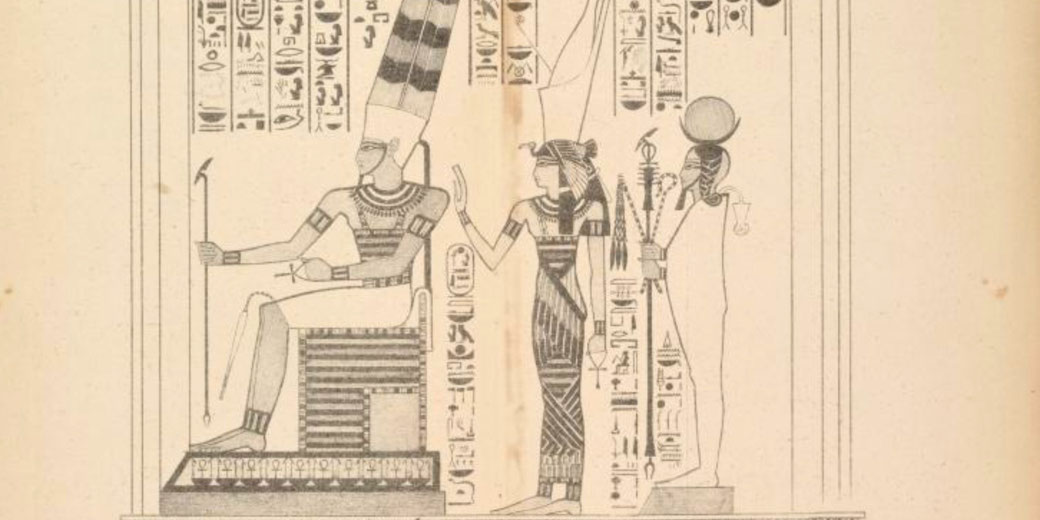

By undertaking these actions, the god’s wife was seen as embodying aspects of both Hathor and Mut, goddesses who were often linked to fertility, motherhood, and queenship.

How did someone become the ‘god’s wife of Amun’?

Typically, the position was reserved for women of the royal family, which meant that only queens or princesses were eligible to hold this prestigious title.

Initially, a king or pharaoh appointed his wife or close female relative to this role.

This direct relationship between the pharaoh and the god’s wife solidified the connection between the royal family and the powerful priesthood of Amun.

As a result, the pharaoh could maintain control over the temple’s wealth and influence, while the god’s wife acted as a religious intermediary for the king’s divine authority.

In addition, the god’s wife of Amun had to undergo specific rituals and ceremonies to legitimize her position.

She was expected to embody the goddess Hathor and perform vital religious duties in the temple.

These responsibilities highlighted the dual nature of the position, which was both spiritual and political in scope.

As the role continued to evolve, it became common for the title to pass from one generation to the next, often within the same family.

For instance, Queen Hatshepsut, who was appointed god’s wife of Amun before her rise to the throne, inherited the title from her predecessor.

This hereditary nature of the title ensured continuity in the relationship between the temple and the royal family.

Moreover, the appointment of the god’s wife was frequently accompanied by a formal investiture ceremony, during which she received sacred objects, such as the ceremonial scepter and the ankh, symbols of her religious and political authority.

What did the god’s wife do?

The god’s wife was entrusted with the important task of maintaining the purity of the temple, which was central to the proper worship of Amun.

This included every aspect of the temple’s operations, from the preparation of offerings to the physical upkeep of sacred spaces.

She performed the ‘ritual of washing’, in which she cleansed the statue of Amun each morning before adorning it with fine garments and jewelry.

Since the statue was believed to house the god’s ka, or spiritual essence, which was thought to require regular care, this responsibility was crucial.

Moreover, during the annual Opet Festival, which celebrated the renewal of the pharaoh’s divine power, the god’s wife of Amun led processions through the streets of Thebes.

She walked alongside the priests of Amun as the sacred barque of the god was carried from Karnak to Luxor.

Political power beyond the temple walls

As the New Kingdom progressed, the title of god’s wife of Amun transformed from a religious position into one of significant political power.

This evolution was closely tied to the rise of the Amun priesthood, which became increasingly influential in both religious and state affairs.

Royal women who were appointed as god’s wives controlled not only temple revenues but also vast estates and agricultural lands.

These resources placed them in a powerful position within Egypt's hierarchy.

In 1539 BCE, Ahmose-Nefertari became one of the most famous early holders of the title.

She was both the wife and sister of Pharaoh Ahmose I, who founded the 18th Dynasty and successfully drove out the Hyksos invaders.

She wielded influence over temple revenues, controlled substantial land holdings, and enjoyed significant autonomy, which was uncommon for women of that era.

Her status in society reflected the importance of Amun’s priesthood, which had become one of the wealthiest and most powerful institutions in Egypt by this time.

Later in the New Kingdom, Hatshepsut, who was appointed god’s wife of Amun before she became pharaoh, expanded the political reach of the title.

As pharaoh, she maintained close ties with the temple, continuing to act as both god’s wife and ruler of Egypt.

Hatshepsut also used her authority to commission large-scale building projects, including the famous temple at Deir el-Bahri, which reinforced her divine status and her relationship with Amun.

Across the New Kingdom, the god’s wives who held this office played an increasingly active role in government, often becoming critical allies of the pharaohs they supported.

Their ability to control temple resources and influence the priesthood allowed them to affect decisions related to military campaigns, economic policy, and even succession.

In other words, the title became a tool through which royal women could exert political influence, ensuring the stability of their families and the kingdom.

The decline of the god's wife of Amun

As the New Kingdom drew to a close, the power of the god’s wife of Amun began to wane.

Due to the increasing dominance of the high priests of Amun, the role of the god’s wife became more symbolic.

By the late 20th Dynasty, Egypt faced internal strife and external invasions, which led to a weakened central government.

The priesthood, particularly in Thebes, began to assert greater control, diminishing the authority of the royal family and, with it, the importance of the god’s wife.

Following this decline, the Third Intermediate Period saw the title briefly revived in Thebes, particularly through the god’s wife of Amun Shepenupet I, who was appointed by the 23rd Dynasty.

However, the role no longer carried the same level of political influence.

Shepenupet I’s position was largely ceremonial, and she acted more as a figurehead under the control of the ruling Libyan pharaohs.

This led to a shift in how the title was viewed. It was used to strengthen alliances between different regions of Egypt rather than serve as a direct tool of political power.

By the Late Period, the title had all but disappeared, but its influence on Egypt’s religious structure remained visible.

Thanks to the centuries-long tradition of intertwining religious and political authority, the concept of a powerful priestess figure persisted in Egypt’s religious hierarchy.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.