The 8 greatest female rulers of the ancient world

Whenever people talk about the great people of history, most discussions focus on male rulers: either powerful kings or mighty emperors.

However, there is a select group of exceptional women who defied the norms of their time to wielded supreme power.

From the sands of Egypt to the hills of Greece, these formidable female leaders here are the names that we need to talk more about.

1. Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII was the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt.

Her reign began in 51 BCE, following the death of her father, Ptolemy XII.

Initially, she co-ruled with her younger brother, Ptolemy XIII, but their relationship soon deteriorated, leading to a civil war.

In this turmoil, Julius Caesar arrived in Egypt in 48 BCE. Cleverly, Cleopatra saw an opportunity in Caesar's presence and famously had herself smuggled into his quarters wrapped in a carpet.

With Caesar's support, Cleopatra regained her throne and subsequently bore him a son, Ptolemy XV, known as Caesarion.

However, following Caesar's assassination in 44 BCE, she had to align herself with Mark Antony, one of his power-hungry successors.

Their relationship was both romantic and political, producing three children and forming a powerful bond against their common enemy, Octavian.

In the famous naval Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, Cleopatra and Antony faced Octavian's forces.

Sadly, they were decisively defeated. After the battle, Cleopatra retreated to her palace in Alexandria where she attempted to negotiate with Octavian.

However, realizing that her efforts were futile, in 30 BCE, Cleopatra committed suicide, reportedly by allowing an asp to bite her.

Egypt then became a province of the Roman Empire.

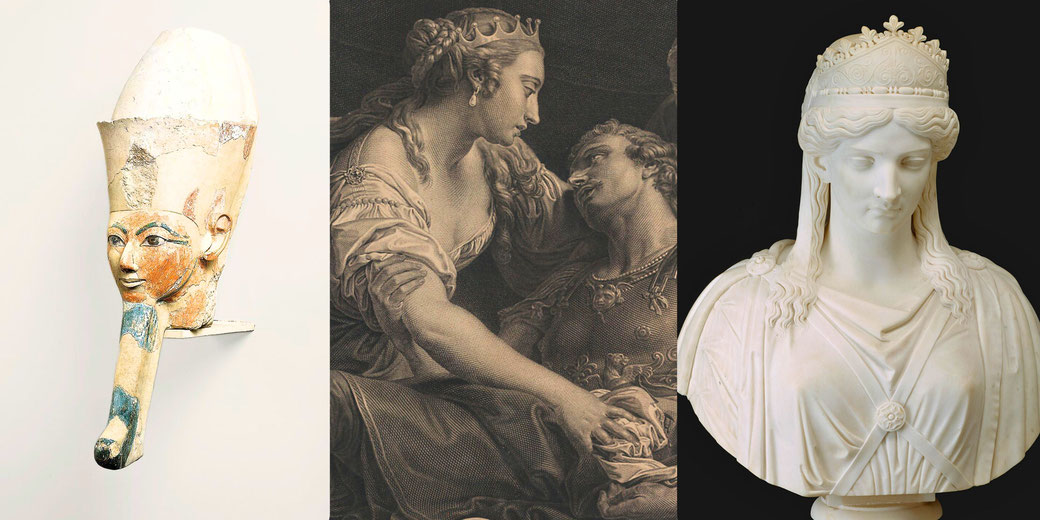

2. Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut was one of ancient Egypt's most remarkable rulers. She ascended to the throne as regent for her stepson, Thutmose III, who was too young to rule following the death of his father, Thutmose II.

Over time, Hatshepsut transitioned from regent to co-ruler, and eventually declared herself pharaoh.

She adopted the regalia and symbols of pharaonic authority to reinforce her legitimacy.

During her reign, Hatshepsut focused on economic prosperity and architectural achievements rather than military conquests.

She initiated trading expeditions, most notably to the Land of Punt, which brought back wealth and exotic goods such as incense, ebony, and ivory.

In addition, these ventures helped to secure Egypt's economic stability and enriched the royal treasury.

In addition, Hatshepsut's reign was also marked by an extensive building program.

Her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri is one of her most enduring and impressive constructions.

Despite her successes, Hatshepsut's legacy faced challenges after her death.

Thutmose III, who eventually became sole ruler, is believed to have attempted to erase her from historical records.

Many of her statues were defaced, and her name was removed from some inscriptions.

However, modern archaeological discoveries have helped to restore Hatshepsut's rightful place in history as one of Egypt's most successful and innovative rulers.

3. Zenobia

Queen Zenobia, who famously challenged the might of Rome in the 3rd century CE, ascended to power after the death of her husband, Odaenathus.

He had established Palmyra as a significant power in the Eastern Roman Empire.

Once in power, Zenobia expanded her realm by conquering territories that included parts of Egypt and Asia Minor.

Her ultimate aim was to create an independent empire centered around Palmyra, which would rival Rome itself.

To her credit, Zenobia was not only a skilled military leader but also a patron of culture and learning.

As a result, Palmyra flourished under her reign and became a center of trade and scholarship.

She was well-known for her intelligence and fluency in multiple languages, including Aramaic, Greek, and Egyptian.

However, her expansionist policies eventually led to conflict with Rome. In 270 CE, Emperor Aurelian launched a campaign to reclaim the territories seized by Zenobia.

The conflict culminated in the Battle of Immae, where Zenobia's forces were soundly defeated.

Following it, she retreated to Palmyra but was eventually captured by the Romans while attempting to flee to Persia.

Zenobia was then taken to Rome as a prisoner, where she was paraded in Aurelian's triumphal procession.

The fate of Zenobia after this event is uncertain. Some accounts suggest she was granted a villa and lived out her days in comfort, while others claim she starved herself to death.

4. Boudica

Boudica, Queen of the Iceni, is a legendary figure in British history, renowned for her fierce rebellion against Roman rule in the 1st century CE.

After the death of her husband, King Prasutagus, the Romans ignored his final will and testament, which had left half of his kingdom to the Roman Emperor and the other half to his daughters.

Instead, the Romans annexed the entire kingdom, flogged Boudica, and abused her daughters.

Enraged by this injustice, Boudica rallied the Iceni and neighboring tribes to rise up against the Roman occupiers.

In 60 or 61 CE, Boudica's forces launched a devastating campaign, attacking Roman settlements and military outposts.

They first targeted Camulodunum (modern-day Colchester), a major Roman colony, and razed it to the ground.

The rebels then advanced on Londinium (London) and Verulamium (St. Albans), leaving a trail of destruction in their wake.

These attacks sent shockwaves through the Roman Empire, as Boudica's army, numbering in the tens of thousands, seemed unstoppable.

However, the tide turned when the Roman governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, regrouped his forces and confronted Boudica's army in a decisive battle.

The exact location of the battle is unknown, but it is believed to have taken place somewhere in the Midlands.

The Romans, despite being outnumbered, achieved a crushing victory.

Boudica is said to have either died in battle or taken her own life to avoid capture.

Boudica has since become an enduring symbol of defiance and the struggle for justice: remembered for her courage and determination in the face of overwhelming odds.

5. Artemisia

Artemisia I of Caria was the queen of Halicarnassus, a Greek city-state under Persian control, in the early 5th century BCE.

Artemisia was a loyal ally of King Xerxes I of Persia, and she commanded five ships in the Persian fleet during the invasion of Greece.

In particular, in 480 BCE, during the Battle of Salamis, Artemisia distinguished herself as a cunning naval strategist.

Despite being part of the larger Persian force, which numbered over 1,200 ships, she advised Xerxes against engaging the Greek fleet in the narrow straits.

However, Xerxes disregarded her counsel, leading to a disastrous defeat for the Persians.

Amidst the chaos of the battle, Artemisia managed to escape by ramming one of her own ships, which was mistakenly believed to be an enemy vessel by the pursuing Greeks.

Her actions during the battle earned her the admiration of both friends and foes.

Xerxes, impressed by her bravery and intelligence, is said to have exclaimed, "My men have become women, and my women, men!"

Following the Persian retreat, Artemisia returned to Caria, where she continued to rule until her death.

She is one of the few female military commanders from antiquity to be remembered for her achievements in conflict.

6. Tomyris

Tomyris, Queen of the Massagetae, was a formidable ruler known for her fierce resistance against the Persian Empire.

In the 6th century BCE, she led her nomadic people, who resided in the region around the Aral Sea, in what is now Central Asia.

Her most famous encounter was with Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian Empire.

Cyrus sought to expand his territory by conquering the Massagetae, but Tomyris warned him not to underestimate her people.

Despite her warnings, Cyrus launched an attack, initially gaining the upper hand by capturing Tomyris' son, Spargapises.

However, the tide turned when Spargapises, upon regaining his freedom, took his own life in despair.

Enraged by this loss, Tomyris vowed revenge; she rallied her forces for a decisive battle.

In this clash, the Massagetae emerged victorious, dealing a crushing blow to the Persians.

Tomyris' victory was both a tactical triumph and a successful personal vendetta.

She is famously said to have sought out Cyrus' body on the battlefield, decapitating him and then placing his head in a wineskin filled with human blood.

According to the historian Herodotus, she declared, "I warned you that I would quench your thirst for blood, and so I shall."

7. Olympias

Olympias of Epirus was the mother of the legendary Alexander the Great.

Born around 375 BCE, she was the daughter of Neoptolemus, the king of the Molossians, an ancient Greek tribe in Epirus.

Olympias' marriage to King Philip II of Macedon in 357 BCE was a political alliance that would produce one of history's most renowned conquerors.

Olympias was known for her strong personality. But she was also deeply involved in the religious and political intrigues of her time.

She was a devout follower of the Dionysian mystery cult, which some believe influenced her son's perception of his semi-divine status.

Following the assassination of Philip II in 336 BCE, Olympias played a crucial role in securing the succession of Alexander to the throne.

She maintained a correspondence with her son during his continual campaigns to exerted control over Macedon.

However, Olympias' later life was full of conflict and strife. After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, she became embroiled in the Wars of the Diadochi, the struggles for power among Alexander's generals.

In 317 BCE, Olympias seized control of Macedon and executed several of her enemies, including King Philip III Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother.

Her actions, however, led to her downfall. Later that year, she was captured by Cassander, one of Alexander's former generals, and was executed.

Olympias' legacy is complex; she is remembered both as a devoted mother and a ruthless political player.

Sadly, her life was deeply intertwined with the rise and fall of the Macedonian empire.

8. Wu Zetian

Empress Wu Zetian is renowned for being the only woman to rule as emperor in the long history of China.

Born in 624 CE during the Tang Dynasty, Wu Zetian rose from a concubine to the powerful consort of Emperor Gaozong.

She was able to do this due to her intelligence, political acumen, and, according to some accounts, ruthless ambition.

After the death of Emperor Gaozong in 683 CE, Wu Zetian initially served as regent for her sons, who succeeded to the throne in turn.

However, in 690 CE, she declared herself emperor. She founded the Zhou Dynasty, breaking the centuries-long tradition of male leadership.

During her rule, Wu Zetian implemented a series of reforms aimed at reducing the power of the aristocracy and strengthening the central government.

She expanded the imperial examination system. This allowed individuals from non-aristocratic backgrounds to enter the civil service.

This not only diversified the bureaucracy but also consolidated her control over the administration.

Additionally, she was a patron of Buddhism, which flourished during her reign.

However, he faced opposition from Confucian scholars, who were critical of a woman's rule.

This may have been in response to the reputation she had of dealing too harshly with her enemies.

Nevertheless, her reign was a period of relative stability and prosperity.

Eventually, Wu Zetian abdicated in 705 CE in favor of her son, Emperor Zhongzong, and she died later that year.

While she is remembered both as a capable ruler who contributed to the development of the Tang Dynasty, her ascent to power was considered to problematic for many later male historians.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.