Who were Hyksos and how did they come to rule over ancient Egypt?

The Hyksos, a group of mixed Asiatic peoples, emerged as a significant force in the landscape of ancient Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, around 1650 to 1550 BCE.

Their arrival and subsequent rule over parts of Egypt marked a period of profound change in Egyptian history. The Hyksos are credited with introducing the horse and chariot, as well as advanced weaponry and fortification techniques, which had a lasting impact on Egyptian military and societal structures.

The origins and identity of the Hyksos

Emerging during the Second Intermediate Period of ancient Egyptian history, the Hyksos were a group of people of mixed Asiatic descent, who are believed to have migrated from the Near East to the Nile Delta.

The term 'Hyksos,' meaning 'rulers of foreign lands' in Egyptian, was originally used to describe their role rather than their ethnicity.

Key figures in their rise to power include Salitis, who is often credited as the founder of the Hyksos dynasty in the Egyptian city of Avaris, now known as Tell el-Dab'a.

Their presence in Egypt was marked not just by conquest but also by cultural assimilation and exchange.

The Hyksos maintained connections with various Semitic-speaking populations in the Near East, evident in the traces of Canaanite culture found in their art and pottery.

This cultural blend is particularly notable in their adoption of Egyptian and Canaanite deities, as they seamlessly integrated into the religious fabric of Egyptian society.

How they dominated parts of the Egyptian kingdom

Historians generally agree that the Hyksos began to settle in Egypt around the end of the Middle Kingdom, approximately in the late 17th century BCE.

The weakening of the central authority of the Egyptian pharaohs during this period created a power vacuum that facilitated their gradual infiltration into the country.

Initially, the Hyksos' presence in Egypt was largely peaceful, characterized by gradual migration rather than an outright invasion.

They settled primarily in the eastern Nile Delta, an area that offered fertile lands and strategic access to trade routes.

Over time, as their numbers and influence grew, the Hyksos transitioned from being settlers to rulers of a significant part of northern Egypt.

The peaceful coexistence with the native Egyptians gradually shifted as the Hyksos began to exert more control.

Notably, the Hyksos kings managed to extend their influence southward, imposing their authority over Middle Egypt.

This expansion was met with resistance from the Seventeenth Dynasty rulers based in Thebes, in Upper Egypt, setting the stage for future conflicts.

The most notable kings of the Hyksos Dynasty include Khyan, Apepi (also known as Apophis), and Khamudi.

Khyan's reign is particularly significant for the expansion of trade with regions outside of Egypt, as evidenced by the discovery of artifacts bearing his royal seal as far as Crete and Babylon.

Apepi, one of the longest-reigning Hyksos kings, is well-documented for his conflicts with the Theban rulers of the Seventeenth Dynasty in the south.

How the Hyksos changed Egyptian culture and warfare

One of the most enduring contributions of the Hyksos was the introduction of the horse and chariot to Egypt.

This innovation revolutionized Egyptian military tactics, giving them a significant advantage in warfare that persisted into the New Kingdom era.

The chariot, initially a symbol of Hyksos power, was adeptly adopted and refined by the Egyptians, who used it effectively in their armies and depicted it prominently in their art and iconography.

In addition to military technology, the Hyksos also introduced new tools and methods in metallurgy, particularly in the working of bronze.

This period saw an improvement in the quality and variety of bronze tools and weapons, a development that had lasting implications on Egyptian craftsmanship and trade.

The Hyksos' influence in pottery and ceramics is also notable, with distinct Asiatic styles blending with traditional Egyptian techniques.

This fusion resulted in unique artistic expressions, visible in the archaeological remnants from this period.

Also, the Hyksos brought with them their own deities, but they also showed reverence to Egyptian gods, particularly Seth, a god often associated with Asiatic peoples.

This led to an increased prominence of Seth in the Egyptian pantheon during and after the Hyksos period.

The cross-cultural exchanges extended to administrative practices as well.

The Hyksos adopted many Egyptian administrative systems, while also introducing their own, which influenced the bureaucratic practices of subsequent Egyptian dynasties.

How the Hyksos were finally driven from Egypt

In the early 16th century BCE, the Egyptian rulers in the southern city of Thebes began a war of liberation to seize back the Delta region from the Hyksos and to reunite the Egyptian kingdom once more.

The Theban kings, viewing the Hyksos as foreign usurpers, sought to reclaim the unity and sovereignty of Egypt.

The most notable Theban king in the early stages of this conflict was Seqenenre Tao, who began military campaigns against the Hyksos.

His efforts, however, were met with limited success, and his reign was cut short, possibly due to circumstances related to the war.

Seqenenre Tao's campaign set the stage for his successors, Kamose and Ahmose I, to continue the fight for liberation.

Kamose, in a series of military campaigns, managed to weaken the Hyksos’ hold on Lower Egypt, as evidenced by his inscriptions detailing victories and raids into Hyksos territory.

His efforts brought the Theban forces closer to Avaris, the Hyksos stronghold.

The decisive phase of the war was led by Ahmose I, the brother and successor of Kamose.

He launched a full-scale campaign against the Hyksos, beginning around 1550 BCE.

His military strategy involved both land and naval assaults, effectively cutting off Avaris from external support and supply routes.

The siege of Avaris, which marked the climax of the war, eventually led to the Hyksos' surrender and expulsion from Egypt.

Following their defeat, the Hyksos were forced to retreat to their homeland in the Near East.

The exact nature of their departure, whether it was a negotiated retreat or a forced expulsion, is still a matter of discussion among historians.

However, the outcome was unequivocal: the Hyksos' departure signified the restoration of Egyptian sovereignty over the entire Nile valley.

What archaeological evidence remains of the Hyksos?

Recent archaeological discoveries have shed new light on the Hyksos period and their influence in ancient Egypt.

One of the most significant findings is the ongoing excavation at Tell el-Dab'a, the site of the ancient city of Avaris, the Hyksos capital.

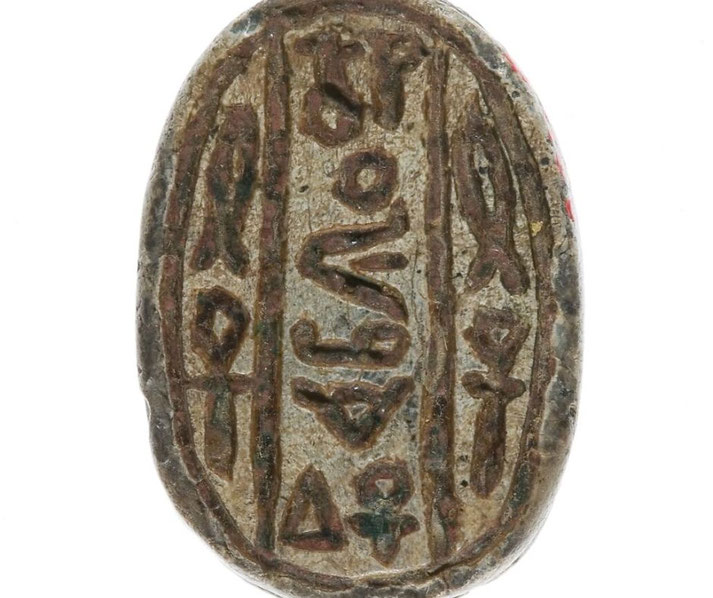

Here, archaeologists have unearthed a wealth of artifacts and architectural remains that offer insights into the life, culture, and administration of the Hyksos in Egypt.

These include large palatial structures, fortifications, and a variety of artifacts that demonstrate a blend of Egyptian and Asiatic styles, reinforcing the idea of cultural integration during their rule.

In 2020, a team of archaeologists discovered a collection of 13 intact Hyksos tombs at the site of Dahshur, south of Cairo.

These tombs, which date back to the 15th and 16th dynasties, contained a rich array of burial goods, including pottery, jewelry, and bronze tools, offering a glimpse into the funerary practices and material culture of the time.

Significantly, the style of the tombs and the artifacts found within them suggest a fusion of Egyptian and Asiatic influences, echoing the broader cultural dynamics of the Hyksos period.

Another noteworthy discovery was made in 2019 at the ancient site of Tell el-Samara in the Delta region.

Here, archaeologists uncovered evidence of a Hyksos-era settlement that predates the known arrival of the Hyksos in Egypt.

This finding suggests that the migration of Asiatic peoples into the Nile Delta may have occurred earlier than previously thought, contributing to a better understanding of the origins and gradual infiltration of the Hyksos in Egypt.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.