What happened to Julius Caesar's assassins?

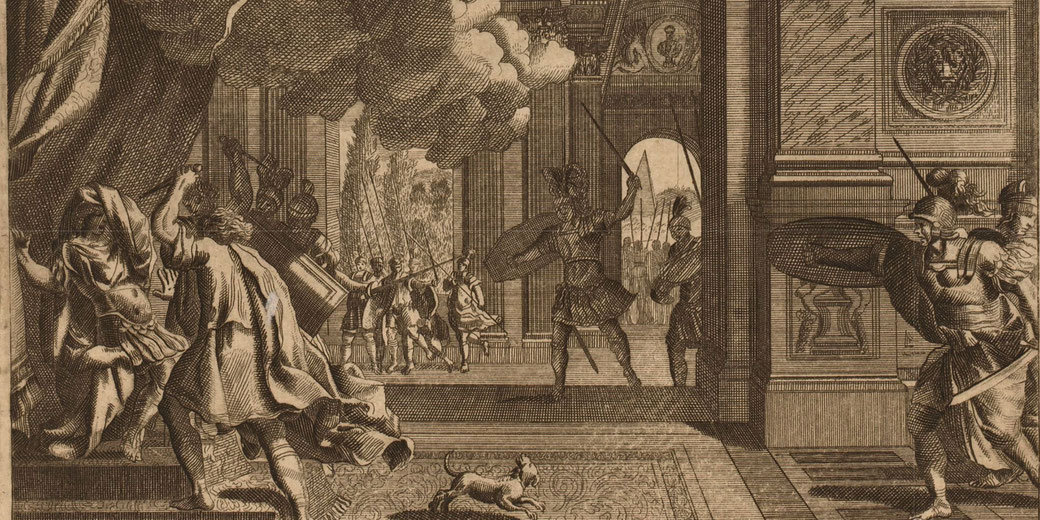

Power shifted in an instant when, on 15 March 44 BCE, senators gathered beneath the roof that curved over the Theatre of Pompey and brought down the most powerful man in Rome with twenty-three knife wounds.

They believed that their act would free the Republic from tyranny and restore liberty, but their calculations failed to anticipate how Caesar’s death would largely undo the political order that he had built.

As the assassins raised bloodied blades and hailed the rebirth of Rome’s constitution, the city reacted with alarm, and the civil wars they had tried to prevent began once more.

What happened on the Ides of March?

During the final months of his life, Julius Caesar held absolute control over Rome.

After a series of military victories, the Senate had named him dictator perpetuo, granting him lifelong authority over legislation and command of the military and placing civic life under his control.

As his honours had accumulated, his public image had shifted from that of a popular war hero to a figure whom many believed had become too powerful to tolerate.

Some senators feared that he might plan to claim the title of king, which would have directly violated Rome’s republican traditions that had stood since the fall of the monarchy in 509 BCE.

In this atmosphere of suspicion, a conspiracy had formed. The plot had reportedly involved over sixty senators, although only a core group of about twenty men would actually carry out the attack.

Among the plotters were Cassius Longinus, Decimus Brutus, and Marcus Junius Brutus, who each had long-standing ties to Caesar.

After they had planned for weeks, they selected 15 March for the attack, a date that was already widely associated with bad omens.

That morning, Caesar prepared to attend a Senate session that had been relocated to the Theatre of Pompey because the Curia had been destroyed by fire in 52 BCE and had not yet been rebuilt.

Calpurnia, who was his wife, pleaded with him to stay home due to a dream that warned of bloodshed, but he confidently dismissed her concerns and proceeded to the chamber.

As Caesar arrived and took his seat, the conspirators surrounded him under the pretext of delivering a petition.

Tillius Cimber approached first and presented a request that his exiled brother be recalled.

When Caesar refused to stand, Cimber grabbed his toga and pulled it back, which created a signal that unleashed the assault.

Casca reportedly lunged first and drove his blade into Caesar’s shoulder, after which the others joined in.

Caesar attempted to resist but collapsed under the sheer number of wounds.

According to some surviving reports, he uttered no final words, although others claimed that he spoke to Brutus in disbelief before falling at the foot of Pompey’s statue.

Once the deed was done, the conspirators exited the building and marched through the streets and called for liberty and the restoration of republican freedom.

They had initially expected a surge of support from the citizenry and imagined that the removal of Caesar would be seen as a return to constitutional order.

However, the Roman population, confronted with the public killing of a beloved leader, responded with alarm and disorder.

Rome in chaos: The aftermath of Caesar's murder

In the immediate aftermath, the conspirators found themselves trapped by uncertainty largely because they lacked a formal plan for government or security.

They retreated to the Capitoline Hill, where they attempted to justify their actions and negotiate a settlement with the remaining senators.

Mark Antony had served as Caesar’s trusted consul and military subordinate, and he quickly chose to play the role of mediator.

To prevent immediate civil violence, he initially proposed a pardon for the assassins and arranged for Caesar’s will to be honoured and his appointments to be confirmed.

For a few days, peace appeared possible, but the funeral of Julius Caesar dramatically changed everything.

At Antony’s direction, the body was displayed before the people, wrapped in bloodstained robes and lifted high on a makeshift bier.

In his oration, Antony spoke with a show of sorrow and used deliberate pauses and emotional appeals to provoke grief and fury.

He read from Caesar’s will, which granted 300 sesterces to every Roman citizen and left his gardens across the Tiber for public use.

However, though the public was moved by anger and responded with rioting. Crowds ran through the streets, and several homes linked to the conspirators were burned.

The Senate house itself, which was a symbol of elite authority, also fell victim to the fury.

Brutus and Cassius, who had effectively become hunted men rather than public saviours, fled the city and attempted to regroup.

Other conspirators escaped to sympathetic provinces or sought refuge with governors who had opposed Caesar’s centralisation of power.

Antony seized the moment. With Caesar’s documents and treasury under his control and the loyalty of key legions behind him, he positioned himself as the true guardian of Caesar’s memory.

He also successfully used the chaos to sideline rivals and strengthen his position, while still projecting the image of someone who acted for the good of the Republic.

Meanwhile, another contender emerged: Gaius Octavius, who was later known as Octavian, arrived in Italy after he learned of Caesar’s death.

Although only eighteen years old, he had been adopted as Caesar’s heir after his death in the dictator’s will, which surprised many contemporaries and provided him with a legal claim as well as significant public interest.

He promised to fulfil Caesar’s bequests and allied himself with unhappy senators, and he rapidly began to gather troops and political support.

Initially, the Senate welcomed Octavian’s rise, viewing him as a useful counterbalance to Antony’s growing power.

However, as Octavian raised a private army composed of Caesar’s veterans and seized command of several legions in northern Italy, it became clear that he did not intend to remain secondary in importance.

After Antony was defeated at Mutina in 43 BCE by the senatorial forces under the consuls Hirtius and Pansa, who both died from their wounds, Octavian returned to Rome and demanded the consulship for himself.

He marched on the city with eight legions, and the Senate, unwilling to resist another armed strongman, granted his request.

How did the Second Triumvirate come to power?

After securing his control of Rome, Octavian reached an agreement with Antony and Marcus Lepidus to effectively divide control of the Republic.

The result was the formation of the Second Triumvirate in November 43 BCE, a legally established commission that was granted extraordinary powers for five years under the Lex Titia.

Unlike the informal First Triumvirate, this alliance operated as an official office with constitutional backing, allowing the Triumvirs to bypass traditional checks and issue commands with few legal limits.

One of their first acts was the creation of proscription lists. Anyone who was suspected of opposing the new regime or of having supported the assassins was often marked for death.

Their properties were taken, their families exiled or killed, and their names erased from public records.

The most famous victim of this purge was the orator Cicero, who had fiercely criticised Antony in a series of speeches known as the Philippics.

Despite Octavian’s initial reluctance, he allowed Cicero’s inclusion on the lists as part of the political bargain.

Cicero was executed while attempting to flee, and his severed hands and head were publicly displayed on the Rostra as a grim display of revenge.

The fall of Brutus and Cassius at Philippi

With Rome purged of dissent, the Triumvirs turned their attention eastward.

Brutus and Cassius had not remained idle. After they fled Rome, they had taken control of Roman provinces in the East and used the local tax revenue to raise powerful armies.

From Asia Minor and Syria, they had raised legions and gathered ships to challenge the Triumvirate’s control.

The Senate’s official support still rested with them, and many believed they represented the last hope of republican freedom.

To confront this threat, the Triumvirs launched a joint campaign into Macedonia and, in 42 BCE, two major battles occurred near the city of Philippi.

The first clash, fought on 3 October, resulted in a mixed outcome, as Brutus succeeded in defeating the division under Octavian’s command, which had been temporarily led by another officer due to Octavian’s illness, while Cassius’s troops were overwhelmed by Antony’s superior tactics.

Cassius believed that the entire battle had been lost, and he took his own life with the help of a freedman before learning of Brutus’s partial success.

A second battle followed on 23 October. This time, the Triumvirs coordinated their attack more effectively and achieved a complete victory.

When Brutus realised that the cause was lost and that desertions had begun among his remaining men, he withdrew into the nearby hills.

That evening, he committed suicide, and his death brought the end of organised senatorial resistance to Caesar’s heirs.

What happened to the other assassins?

Once the main leaders had fallen, the Triumvirs turned their attention to the remaining conspirators.

Each man who had raised a dagger against Caesar faced punishment, exile, or violent death.

Decimus Brutus was one of the chief planners and had attempted to maintain control of Cisalpine Gaul but found himself abandoned when his troops refused to follow him

As he fled toward Macedonia, he was intercepted by a Gallic warlord who handed him over to Antony’s allies, who executed him without ceremony.

Gaius Trebonius was another senior conspirator who had governed Asia and met a violent death.

In early 43 BCE, Publius Dolabella, who was a loyalist to Caesar and one of the men appointed consul after his death, entered the city of Smyrna.

He arrested Trebonius and ordered his execution by decapitation. The severed head was then displayed publicly on a rostrum in the forum of Smyrna as a demonstration of loyalty to Caesar’s memory.

Lucius Tillius Cimber, who had grabbed Caesar’s toga to initiate the attack, operated as a naval commander in the eastern Mediterranean for a short time.

He supported Brutus and Cassius during the Philippi campaign, though no reliable records describe his death.

Most accounts suggest that he either died in battle or was killed during the post-Philippi purges, although his fate ultimately remained unknown.

Servilius Casca, who had delivered the first strike, also followed Brutus eastward.

His role in the conspiracy was well known. Some accounts suggest that he committed suicide after the defeat at Philippi, though this is not universally accepted.

Many lesser conspirators, whose names were omitted from surviving records, had faded into obscurity.

Some were hunted and killed by local authorities or assassins, while others may have died in hiding. Few, if any, escaped retribution.

The Triumvirs treated Caesar’s murder as both a political crime and a personal betrayal, and they used every tool at their disposal to ensure the Liberatores received no shelter.

By the time Octavian defeated Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BCE and was granted the title Augustus in 27 BCE, the political world that had produced Caesar’s assassins no longer existed.

The Republic had vanished in all but name, and the emperorship that followed had its source in both Caesar’s life and the consequences of his murder.

In seeking to preserve the old system, the assassins had ensured its destruction.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.