Who was Brutus and why did he kill Julius Caesar?

On a chilly day in March, beneath the marble arches of Rome’s Senate, the fate of the Republic unraveled in a single, violent act: the assassination of Julius Caesar.

Among the senators who drove their daggers into Caesar, none struck deeper—emotionally or politically—than Marcus Junius Brutus.

Why did he turn against a leader who had shown him mercy and favor?

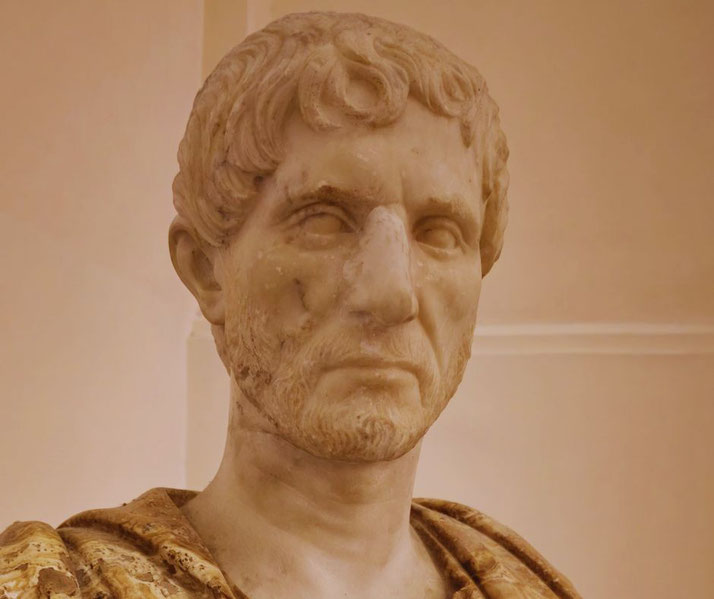

Who was Marcus Junius Brutus?

Marcus Junius Brutus was born in 85 BCE to a distinguished Roman family. His mother, Servilia, was the half-sister of Cato the Younger, a staunch defender of the Republic, while his father was a governor who was killed in 77 BCE after attempting to overthrow Pompey.

Raised in this environment of political fervor, Brutus grew up immersed in the ideals of the Roman Republic, which valued liberty and senatorial authority above all.

His family’s long-standing connection to these values, combined with his own education in philosophy, made him a dedicated follower of Stoicism, a philosophy that emphasized duty, virtue, and reason.

In 58 BCE, he served as a financial administrator in Cyprus, where he gained both wealth and reputation.

His intellectual influences were heavily shaped by his uncle Cato and the philosopher Porcia, who urged him to remain true to the Republic’s core values.

His connection to the broader Roman elite made him an influential senator, and he initially supported Pompey during the civil war against Julius Caesar.

Brutus’ relationship with Julius Caesar

Brutus’ mother, Servilia, was widely believed to have been one of Caesar’s lovers.

This may explain, partly, why Brutus sided with Pompey during the Roman Civil War.

However, Caesar treated him with remarkable mercy after Pompey’s defeat at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE.

Instead of punishment, Caesar welcomed Brutus back into his inner circle, granting him significant political roles and ensuring his place within the elite.

This kindness, however, did not erase the political differences between them. Brutus, who was deeply committed to the ideals of the Roman Republic, found Caesar’s rise to absolute power increasingly difficult to accept.

As Caesar accumulated titles and honors, declaring himself dictator for life in 44 BCE, Brutus began to see his actions as a direct threat to Roman liberty.

Meanwhile Caesar continued to show favor to Brutus, appointing him governor of Gaul in 46 BCE and naming him among his potential successors, the political climate around them grew increasingly fragile.

The chaotic political climate of Rome

By the 40s BCE, Caesar had consolidated significant control, first through his military victories and then by assuming key political titles, such as consul and dictator.

Many Romans, particularly the Senate, grew alarmed by this shift, seeing it as a direct assault on the republican ideals that had guided Rome for centuries.

Caesar’s accumulation of power effectively sidelined the Senate, which was traditionally the body responsible for governing Rome through collective decision-making.

The ideals of the Roman Republic centered around a system of checks and balances, known as mos maiorum, or the "way of the ancestors".

This system ensured that no single individual could dominate the political sphere, which meant that authority was divided among elected officials, most notably the Senate and the consuls.

For Romans like Brutus, these principles were essential to maintaining liberty.

Caesar’s rise disrupted this balance, as his role as dictator allowed him to bypass or outright control these governing bodies.

Caesar's dominance of both the military and the political structure made him appear less as a servant of Rome and more as a monarch, something that republican-minded Romans deeply feared.

The fear of monarchy, which had haunted Rome since the expulsion of its last king, Tarquin the Proud, in 509 BCE, drove much of the opposition to Caesar.

In fact, Marcus Junius Brutus' family traced its origins back to Lucius Junius Brutus, the man credited with leading the revolt that expelled Tarquin the Proud.

This act had established the Republic, a system which replaced monarchy with elected officials and senatorial rule.

Specifically, Lucius Junius Brutus became one of the first consuls, and his name was forever associated with the defense of Roman liberty.

As a descendant of this revered figure, Marcus Brutus grew up with the weight of this legacy, which made his role in Roman politics even more significant.

Why did Brutus join the conspiracy?

Many senators believed that Caesar’s actions would eventually lead to the complete destruction of the Republic.

For men like Brutus, the notion of a single ruler controlling Rome was an existential threat to the value of Roman liberty.

The Senate’s growing concern about Caesar’s unprecedented authority, combined with rumors that he planned to declare himself king, heightened the urgency of their opposition.

Caesar’s unprecedented power created a volatile political climate, one in which those committed to the Republic, like Brutus, felt compelled to act before it was too late.

As a philosopher influenced by Stoicism, Brutus believed that the highest duty of a Roman was to protect the Republic’s values of liberty and shared power.

However, personal loyalty to Caesar complicated Brutus’ decision. Caesar had shown him great kindness following the civil war, sparing his life and elevating him to positions of power.

Also, Brutus admired Caesar’s military genius and respected him as a leader, but he could not reconcile this admiration with his duty to Rome.

Other senators, like Cassius, pressured Brutus by reminding him of his noble lineage and his responsibility to uphold the Republic.

They played on his fears that if Caesar were not stopped, Rome would fall into tyranny, and the liberty for which so many had fought would be lost forever.

Cassius, in particular, worked tirelessly to convince Brutus that the assassination was not only necessary but also a noble act of service to the Republic.

As a result, Brutus began to see the conspiracy as his duty, one that required him to set aside personal feelings for the greater good of Rome.

His struggle between loyalty to Caesar and loyalty to Rome weighed heavily on him, but he ultimately believed that his duty to the Republic was more important than any personal bond.

The Ides of March and the assassination of Julius Caesar

In the days leading up to the murder, Caesar had dismissed several warnings about potential danger, including Caesar's wife, Calpurnia, who had a premonition the night before of his upcoming death.

Despite the ominous warnings, Caesar continued to assert his dominance, preparing for a new military campaign against Parthia.

The conspirators, including Brutus, Cassius, and several other senators, saw this as their last chance to prevent Caesar from becoming an outright monarch.

They planned to strike during a Senate meeting, where Caesar would be unprotected and surrounded by those he believed to be his allies.

On the day of the assassination, March 15, 44 BCE, Caesar arrived at the Theatre of Pompey, where the Senate was convening.

He entered without suspicion. The conspirators quickly put their plan into action, with each man assigned a role.

Brutus stood among them. Casca was the first to strike, plunging a dagger into Caesar’s neck.

Chaos erupted as the rest of the conspirators, including Brutus, drew their weapons and attacked.

Caesar initially attempted to resist, but the overwhelming number of conspirators made his efforts futile.

Brutus’ participation in the assassination held deep significance, both for Caesar and for Rome.

According to historical accounts, upon seeing Brutus among his killers, Caesar’s final words were, “Et tu, Brute?”

These words, which are debated in their exact form but widely accepted as Caesar’s last expression, meant, “And you, Brutus?”

Caesar had trusted Brutus, who was not only politically aligned with him at times but also personally close.

Aftermath: Brutus' fate and the fall of the Republic

After Caesar’s assassination, Brutus and the other conspirators initially believed they had liberated Rome from tyranny.

However, their expectations quickly unraveled. Public reaction to Caesar’s death was far from supportive.

Many citizens, who had admired Caesar for his reforms and military victories, reacted with outrage rather than celebration.

Mark Antony, who was Caesar’s loyal ally, used his position and powerful oratory to turn the Roman people against the assassins.

As a result, Brutus and the conspirators were forced to flee Rome.

Brutus and Cassius regrouped in the eastern provinces, where they gathered military support to prepare for the inevitable confrontation with Mark Antony and Octavian, Caesar’s adopted heir.

The ensuing struggle for power resulted in the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE, where Brutus and Cassius faced the combined forces of Antony and Octavian.

In the first engagement, Brutus managed to achieve a temporary victory against Octavian’s forces, but the tide soon turned.

Cassius, believing they had lost the battle, took his own life. Brutus, now left to lead the remaining forces, fought valiantly in a second confrontation but was ultimately defeated.

Rather than face capture, Brutus also committed suicide.

Instead of saving the Republic, the conspirators had inadvertently paved the way for its downfall.

With Caesar gone, Rome fell into another series of civil wars as competing factions vied for control.

Octavian and Antony, initially allies in the fight against Brutus and Cassius, eventually turned on each other.

This led to the final collapse of the Republic and the establishment of the Roman Empire.

Octavian, who would later become Augustus, emerged victorious and established a new system of autocratic rule.

Even though Caesar’s death was intended to protect the Republic from tyranny, instead it accelerated its transformation into an empire.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.