What were Marius' Mules? The revolution that created the Roman legions.

The history of the Roman Empire is studded with tales of legendary leaders, ingenious innovations, and military might.

Yet, few stories are as intriguing as the transformation of the Roman military under the stewardship of Gaius Marius, a prominent general and statesman.

Among Marius' numerous contributions, one that stands out is his introduction of 'Marius' Mules' - the legionaries burdened with their personal and military equipment, marching into battles and into history.

But what were Marius' Mules exactly?

How did they change the dynamics of the Roman army?

And what impact did this have on the Roman society and its political landscape?

Who was Marius?

Gaius Marius, a man of humble beginnings, was born in 157 BC in the small Italian town of Arpinum.

He embarked on a military career at a young age, rising through the ranks with a reputation for bravery, discipline, and strategic acumen.

Despite his non-aristocratic origin, Marius' military successes propelled him to the highest echelons of Roman society, allowing him to serve an unprecedented seven terms as consul, the highest elected office in the Roman Republic.

But it was his transformative military reforms that would leave a profound mark on Roman history.

The Roman military, at this time, was not a standing army as we understand it today, but a citizen militia that was raised in times of war.

The system, rooted in Rome's agrarian past, called upon landowning citizens to provide their service and their own equipment when called upon for war.

This approach had served Rome well during its early expansion, but by the late 2nd century BC, cracks were beginning to show.

The escalating scale of warfare, the increasing duration of military campaigns, and the strain on Rome's smallholder farmer-soldiers were all pushing the Roman military system towards a breaking point.

The need for military reform

The Roman military system, despite its past successes, was no longer tenable by the time Gaius Marius came to power.

The continuous campaigns in far-off lands left many Roman farmers unable to tend to their fields, leading to economic hardships and the decline of the small-scale farmer class, the backbone of Rome's traditional militia army.

Meanwhile, Rome's adversaries were growing stronger, employing new tactics and deploying large, well-equipped armies that often outmatched Rome's legions.

The demands of managing and defending an empire required a professional, standing army that could respond quickly to threats, and that was trained and equipped to the highest standards.

The army needed soldiers who were free from the demands of managing their farms and who could serve for extended periods.

But such an army would not come into existence without significant changes to existing military, social, and political structures.

The demands of managing and defending an empire required a professional, standing army that could respond quickly to threats, and that was trained and equipped to the highest standards.

The army needed soldiers who were free from the demands of managing their farms and who could serve for extended periods.

But such an army would not come into existence without significant changes to existing military, social, and political structures.

How Marius revolutionised the Roman army

Amidst the turmoil and challenges facing Rome, Gaius Marius ascended to his first consulship in 107 BC, bringing with him a vision to revolutionize the Roman military.

His reforms were profound, yet practical, designed to address the changing needs of Rome's expanding empire and the socio-political issues plaguing the republic.

The cornerstone of Marius' reforms was the introduction of the volunteer system. Until then, the Roman army had consisted mainly of property-owning citizens, expected to provide their own equipment for service.

Marius broke from this tradition, opening the legions to the capite censi, the 'head count' or lower class of Roman citizens who did not own land.

This was a radical departure from previous norms, as it enabled the underprivileged to join the military and earn a regular wage, thus addressing some of the social issues at play.

In return, these soldiers pledged their loyalty not to the republic, but to their generals, establishing a bond that would have significant political implications in the years to come.

Marius also implemented a significant reorganization of the Roman legions. He standardized training across the legions, ensuring that every soldier knew not only how to fight but also how to construct fortifications, march in formation, and carry out a range of other duties.

This homogenization led to increased efficiency and interoperability among the legions, enhancing Rome's ability to conduct large-scale military campaigns.

The legions themselves were restructured to be more flexible and self-reliant. Marius discarded the manipular formation, an older system based on classes of soldiers with different equipment and roles.

In its place, he implemented the cohort system, dividing each legion into ten cohorts, each with six centuries of soldiers.

This new structure was more adaptable to different battlefield conditions and allowed for better control and coordination of units.

Perhaps the most visible aspect of Marius' reforms was the standardization of equipment.

Before Marius, soldiers were expected to supply their own gear, leading to disparities in quality and type.

Marius issued state-funded equipment to all soldiers, including a standardized kit of weapons and armor.

This change not only improved the army's efficiency and effectiveness but also further enhanced the soldiers' loyalty to their generals, as they were now dependent on them for their equipment and livelihood.

Why were his new soldiers called 'Marius' Mules'?

A noteworthy, yet often understated aspect of Marius' reforms, was the change in the soldiers' burden.

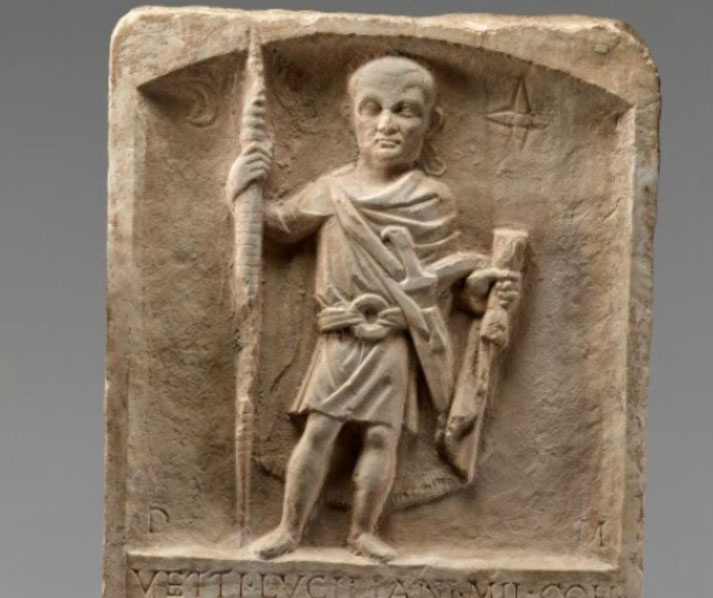

Marius' soldiers were not just better trained and equipped, they also carried their necessities on their backs, earning them the moniker "Marius' Mules."

The Latin phrase "Muli Mariani" perfectly encapsulates the endurance and resilience that became the defining features of these Roman soldiers.

The phrase stems from the fact that, apart from their weapons and armor, each soldier was required to carry a pack (a sarcina) with his personal belongings, food, and equipment needed for camp setup, including a saw, a wicker basket, a piece of rope, a chain, a pot, and a stake (for the construction of palisades).

This pack, weighing around 40-50 pounds, was supported by a forked wooden stick, known as a furca, carried over the soldier's shoulder.

While the additional weight seems counterintuitive to an efficient fighting force, this move aimed to make the Roman legions more self-reliant and mobile.

The soldiers, accustomed to the weight and the rigors of long marches, could set up and break camp rapidly, allowing them to adapt to changing circumstances more effectively.

The need for a baggage train was also reduced, allowing for quicker movement of the legions.

The depiction of Marius' soldiers as mules was not derogatory but rather a recognition of their resilience, strength, and adaptability.

They were not merely fighting machines but versatile troops capable of conducting a wide range of tasks.

Marius' Mules were known for their physical endurance and their ability to sustain prolonged campaigns.

The practice imbued the legions with a strong sense of discipline and camaraderie, as everyone, regardless of rank, shared the burden.

How effective were these new troops?

The effects of Marius' military reforms were felt most directly on the battlefield.

The newly trained and equipped Roman legions - the Mules of Marius - demonstrated their mettle in various famous battles and campaigns, which not only proved the effectiveness of Marius' reforms but also played significant roles in the expansion of the Roman Republic.

Jugurthine War (112-106 BC)

While the Jugurthine War began before Marius' first consulship, his involvement was significant. Marius took command in 107 BC, employing his reformed legions to end the conflict in Numidia (part of modern-day Algeria and Tunisia). The strategies and resilience of Marius' Mules played a pivotal role in the capture of Jugurtha, ending the war and expanding Roman influence in North Africa.

Battle of Aquae Sextiae (102 BC)

The Battle of Aquae Sextiae in southern Gaul (modern-day Aix-en-Provence, France) was one of the most significant victories of the Roman legions under Marius. Here, the Roman forces faced off against the Teutones, one of the Germanic tribes that posed a significant threat to Rome. The Romans, applying the skills and endurance honed by Marius' reforms, managed to trap the Teutones and annihilate their forces. This victory marked a turning point in the Cimbrian War and demonstrated the effectiveness of the newly reformed legions.

Battle of Vercellae (101 BC)

A year later, in the Battle of Vercellae, the Roman legions faced the Cimbri, another Germanic tribe. Once again, Marius led the legions to a decisive victory. This battle in northern Italy marked the end of the Cimbrian War and further cemented the reputation of Marius and his reformed Roman legions.

Social War (91-88 BC)

Though Marius' direct involvement in this war was limited due to his declining health, the newly structured Roman legions played a significant role in the conflict. The war pitted Rome against its Italian allies who sought Roman citizenship. It was a testing ground for Marius' Mules, highlighting their ability to endure lengthy and complex military campaigns.

The fundamental problems created by Marius' reforms

While Gaius Marius' military reforms fundamentally transformed the Roman military and had significant positive impacts on Rome's military prowess, they were not without their critics and controversies.

The implications of these reforms extended beyond the battlefield, profoundly affecting Roman society, economy, and politics, often stirring considerable debate.

One of the primary criticisms of Marius' reforms was the shift in soldiers' loyalty from the state to their generals.

By offering the capite censi a path to economic stability and social mobility through military service, Marius inevitably fostered a strong bond between the soldiers and their generals, who now essentially acted as their patrons.

This dynamic became a source of potential exploitation, as powerful generals could leverage the loyalty of their legions for personal or political gain.

This shift sowed the seeds for the rise of military dictators like Sulla and Julius Caesar, contributing to the eventual downfall of the Roman Republic.

Marius' reforms also had far-reaching socio-economic implications. While they opened up opportunities for the lower classes, they also led to increased militarization of Roman society.

The promise of land at the end of service also exacerbated land distribution problems in Rome, as vast tracts of public land were often given to retiring veterans.

This further contributed to the concentration of wealth in the hands of the few and exacerbated existing social and economic inequalities.

While the introduction of Marius' Mules made the legions more mobile and self-sufficient, it also placed a significant additional burden on the soldiers.

The need to carry their own supplies and equipment increased the physical demands on the soldiers, leading to potential issues with fatigue and morale.

Marius' reforms also played a role in stoking political divisions within Rome. As Marius and his fellow generals accrued more power, political tension between the senatorial class and the popular tribunes grew.

These divisions would eventually erupt into civil war, contributing to the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.