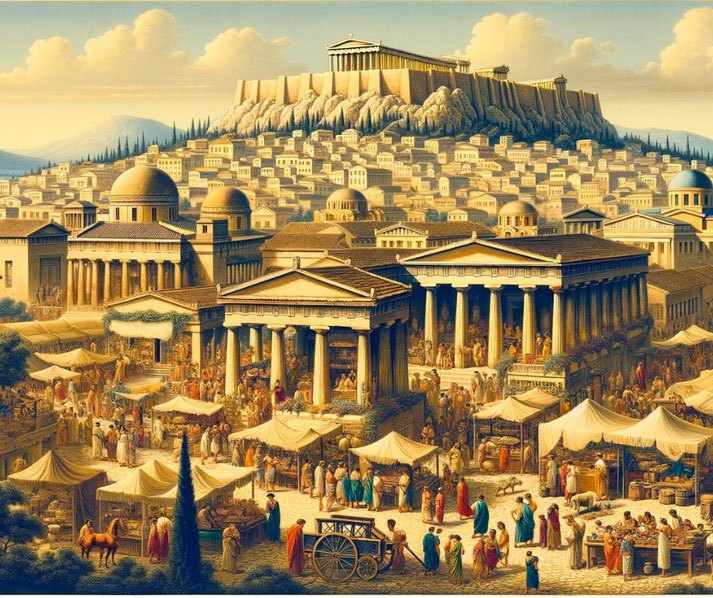

Pericles' visionary leadership of ancient Athens at the height of its power

Pericles, a prominent statesman, orator, and general of Athens during its golden age, is a pivotal figure in the history of Ancient Greece.

His period of influence, roughly from 461 to 429 BCE, coincides with the height of Athenian power and cultural achievement.

Under his guidance, Athens became a center of culture, attracting artists, philosophers, and playwrights.

But it all came crashing down around him in the most tragic of ways.

Pericles' early life

Pericles was born in 495 BCE into an influential and affluent Athenian family. His father, Xanthippus, was a renowned military leader who played a crucial role in the Persian Wars, notably in the Battle of Mycale in 479 BCE.

His mother, Agariste, was a member of the powerful and aristocratic Alcmaeonid family, which had a long history of political prominence in Athens.

This lineage provided Pericles with a strong political foundation and connections that would later support his rise in Athenian politics.

During his formative years, Athens was undergoing significant political and cultural transformations.

The city was moving away from the aristocratic rule towards a more democratic system, a shift that would profoundly influence Pericles' political ideals and strategies.

His education reflected the intellectual vigor of the time. He was tutored by some of the leading minds of his day, including the musician Damon, who is said to have influenced his skills in oratory and leadership.

Pericles also studied under the philosopher Anaxagoras, whose teachings on philosophy and science left a lasting impact on his worldview.

This exposure to a range of disciplines helped develop Pericles into a well-rounded thinker, capable of understanding and addressing various aspects of Athenian life, from politics and military strategy to culture and philosophy.

His entry into the political life of Athens

His early career in politics began in the 460s BCE. He first appeared in the political arena as a prosecutor, challenging the then high-ranking official Cimon, who was a proponent of aristocratic interests and a policy of alliance with Sparta.

This legal victory not only elevated Pericles' status but also signaled a shift in Athenian politics towards more democratic ideals, aligning with Pericles' own beliefs and policies.

In 461 BCE, Pericles played a pivotal role in passing a series of reforms that diminished the power of the Areopagus, a council dominated by the Athenian aristocracy, thereby transferring much of its authority to the more democratic institutions of the ekklesia (assembly) and the heliaia (law courts).

These reforms were crucial in advancing the democratic process in Athens, empowering a broader segment of the population.

How Pericles transformed Athens

The Golden Age of Athens, a period roughly from 480 BCE to 404 BCE, reached its zenith under Pericles' leadership, particularly between 461 BCE and 429 BCE.

This era is distinguished by unprecedented achievements in art, culture, and democracy, largely driven by Pericles' vision and policies.

One of the most iconic symbols of this period is the construction of the Parthenon, which began in 447 BCE on the Acropolis.

This architectural marvel, dedicated to the goddess Athena, was not just a religious sanctuary but also a testament to Athenian power and aesthetic achievement.

The project was part of a larger Periclean building program that included the Propylaea, the Erechtheion, and the Temple of Athena Nike.

These structures, created under the guidance of master artists like Phidias, Ictinus, and Callicrates, showcased the artistic and engineering prowess of Athens.

The cultural landscape of Athens during this time was equally vibrant. The city was a hub for playwrights, philosophers, and artists.

The works of Sophocles, Euripides, and Aeschylus, pivotal figures in the development of drama, were performed in the theatres of Athens.

Philosophers like Socrates questioned and debated on various aspects of life, contributing to the intellectual dynamism of the era.

Pericles' influence extended into the realm of education and the arts. He fostered an environment where arts and intellectual pursuits flourished.

This period saw the growth of rhetoric and philosophy, with the establishment of schools and public forums for debate and discussion.

Pericles' controversial political views

Pericles' vision of democracy was revolutionary for its time and deeply influential in the development of Athenian society.

His democratic principles were rooted in the belief that all citizens, regardless of wealth or social status, should have an equal role in the governance of the state.

This vision was reflected in a series of reforms that he implemented to expand participation in the Athenian democracy.

Central to Pericles' democratic reforms was the idea of 'isonomia', or equality before the law.

He believed that the involvement of every citizen, not just the elite, was essential for the health and prosperity of the state.

This belief led to the introduction of measures that allowed for broader citizen participation in political processes.

One of his most significant reforms was the introduction of pay for public officials and jurors around 450 BCE.

This ensured that even the less affluent citizens could afford to participate in civic duties, effectively democratizing the political system and reducing the dominance of the wealthy elite.

Pericles also championed the assembly (ekklesia) as the central decision-making body of Athens, where every male citizen had the right to speak and vote.

This assembly became the cornerstone of Athenian democracy, allowing for a direct form of governance that was unprecedented at the time.

Under Pericles, the assembly gained increased power and influence, making key decisions regarding laws, war, and foreign policy.

His approach to leadership within this democratic framework was also notable. Pericles was known for his persuasive oratory, which he used to engage with the citizens and influence the assembly.

He respected the democratic process and the opinions of the assembly, even when they contradicted his own views.

His famous Funeral Oration, as recorded by Thucydides, encapsulates his democratic ideals, emphasizing the superiority of the Athenian way of life and governance.

However, Pericles' vision of democracy was not without its critics. Some contemporaries and later historians argued that his leadership style bordered on populism and that his policies were at times too radical.

They contended that his influence over the assembly and the people was so strong that it sometimes overshadowed the democratic process itself.

Pericles' scandalous private life

Pericles was known to have been married twice. His first marriage was to a woman from a notable Athenian family, with whom he had two sons, Xanthippus and Paralus.

However, this marriage ended in divorce. Pericles' more notable and unconventional relationship was with Aspasia of Miletus, a woman of great intellect and charisma, who played a significant role in his life.

Aspasia, often described as his companion and confidante, was a foreign resident in Athens, known for her association with prominent Athenians.

Their relationship was unconventional for the times, given her non-Athenian origin and the nature of their partnership outside the traditional bounds of marriage.

Together, they had a son named Pericles the Younger.

Aspasia herself was a unique and influential figure in Athenian society. She is often credited with having a significant influence on Pericles, especially in his views and policies regarding women and culture.

Her home was a center for intellectual discussion, attracting philosophers and statesmen, including Socrates.

Despite facing criticism and social scrutiny, their relationship endured until Pericles' death.

Throughout his life, Pericles was known for his cautious public demeanor and avoidance of personal ostentation, a contrast to the grandeur of his public achievements.

He maintained a reserved and modest lifestyle, conscious of his public image and the scrutiny that came with his position.

This personal discipline and modesty in lifestyle, despite his powerful status, were traits that earned him respect among his contemporaries.

His military leadership during the Peloponnesian Wars

However, this period was also marked by military endeavors, notably the Peloponnesian War, which began in 431 BCE.

The war, initially a conflict between Athens and Sparta, eventually engulfed much of the Greek world.

Pericles' tenure as a military leader was marked by a blend of strategic foresight and cautious pragmatism.

His military strategies were pivotal during the First Peloponnesian War (460-445 BCE) and the early years of the Second Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE).

Pericles' approach to military leadership reflected his broader vision for Athens, prioritizing the city's long-term stability and prosperity.

During the First Peloponnesian War, Pericles led several military campaigns. His strategy was characterized by a combination of naval strength and selective land engagements.

Recognizing Athens' naval supremacy, he focused on protecting sea routes and extending Athenian influence across the Aegean Sea.

This approach was effective in countering the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League, despite their superiority in land-based warfare.

The outbreak of the Second Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE saw Pericles adopting a defensive strategy.

He proposed the 'Periclean Strategy,' which involved avoiding direct land battles with the Spartan army, instead relying on Athens' naval strength to harass enemy coasts and secure vital supplies.

Pericles advised the Athenians to retreat within the city's Long Walls, a set of fortifications connecting Athens to its port at Piraeus, ensuring a secure supply line from the sea.

This strategy aimed to minimize the risk to Athens while leveraging its naval dominance to wear down the enemy.

The Plague of Athens and the tragic death of Pericles

The Plague of Athens was a devastating epidemic that hit the city in 430 BCE, during the second year of the Peloponnesian War.

This catastrophic event had far-reaching consequences for Athens, both in terms of human cost and its impact on the city's social and political structure.

The origins of the plague are not clearly known, but it is believed to have been brought to Athens through the port of Piraeus, possibly originating in Ethiopia.

It spread rapidly through the city, exacerbated by the overcrowding as Pericles had previously ordered the rural population to move inside the city walls to avoid Spartan attacks.

The cramped and unsanitary conditions created an ideal environment for the spread of disease.

The symptoms of the plague, as described by the historian Thucydides, were horrific and included fever, redness of the eyes, throat and tongue pain, and an unbearable feeling of suffocation.

The disease ravaged the city for about five years, with multiple waves of infection. It is estimated that it claimed the lives of around one-third of the population of Athens.

The social and economic fabric of the city was deeply affected, as not only the general populace but also many skilled workers and leaders succumbed to the disease.

The plague also had a profound impact on Athenian society and morale. Traditional social and religious norms broke down as people struggled to cope with the scale of the disaster.

There was a sense of despair and fatalism, as the Athenians witnessed the rapid spread of the disease and the failure of traditional medicine and religious rites to provide relief.

The plague's impact extended to the political arena as well. The plague claimed the lives of both his legitimate sons, Xanthippus and Paralus, a devastating blow that deeply affected him.

Then, Pericles, who had been the guiding force behind Athens' strategy in the Peloponnesian War and its democratic reforms, also become one its victims, dying in 429 BCE.

His death marked a significant blow to Athens, as it lost its most influential leader at a critical juncture.

The absence of his leadership led to a period of political instability and changes in strategic direction in the ongoing war with Sparta.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.