How the gruesome Plague of Justinian shook the Byzantine Empire

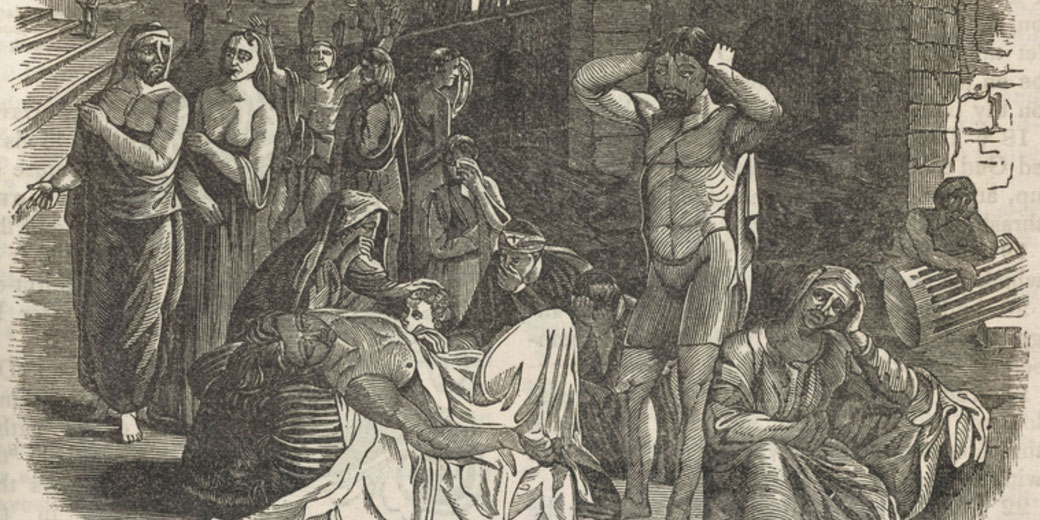

In the year AD 541, during the reign of Emperor Justinian I, a deadly epidemic broke out that severely damaged large parts of the population of the Byzantine Empire, disrupted its economy, and weakened its military strength.

This outbreak, later named the Plague of Justinian, was the earliest clearly recorded case of bubonic plague in history. It began in Egypt and spread through trade routes to the imperial capital of Constantinople.

The plague left many areas empty of people and changed the direction of the empire's plans in Europe and beyond.

The sudden arrival of the plague

The outbreak began in the Egyptian port city of Pelusium, a key grain-shipping hub on the Mediterranean.

Byzantine merchant ships carried cargo that was likely filled with black rats that had fleas infected with Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that caused plague.

From there, the disease spread quickly through Alexandria and across the eastern Mediterranean, reaching Constantinople by the spring of AD 542.

When it reached the imperial capital, the effects were disastrous. The city, home to hundreds of thousands, saw its population drop suddenly.

Procopius described how bodies were left in the streets and taken away in mass graves. He was a historian who personally witnessed the events.

Symptoms and death toll of the plague

The disease came in several forms. The bubonic plague caused painful swellings in the lymph nodes, known as buboes, usually found in the groin and armpits.

Victims often had high fevers, vomiting, and confusion. The septicaemic type was even deadlier, spreading through the blood and killing quickly, sometimes before buboes even showed.

The pneumonic form infected the lungs and could spread between people through breathing, making it especially easy to catch in crowded areas.

The death rate was shocking. Scholars believe Constantinople may have lost between 30 to 50 percent of its people in the first wave alone.

Procopius said that at its worst, the plague was killing up to 10,000 people per day, though modern historians question that number.

The number of deaths was too much for public services to handle. Burial places filled up, workers who were meant to move bodies died on the job, and the emperor had to order mass graves to be dug outside the city walls.

The city’s markets, courts, schools, and workshops came to a stop.

The impact of the plague on the Byzantine Empire

The human cost soon led to wider problems. The Byzantine economy, which relied on farming, trade, and taxes, declined quickly.

With fewer farmers, fields were left empty, and food became hard to find.

Craftsmen and traders vanished, which caused prices to rise and trade networks to fall apart.

Justinian’s efforts to keep strong central control through taxes had already caused anger, which grew worse in a population hit by illness and death.

Tax income dropped quickly, and the emperor started making more coins using lower-quality metal.

Even though this led to rising prices, it is not clear if the poor-quality coins were a direct result of the plague or part of wider financial choices.

Military strength also fell. Soldiers died in large numbers or left the army in fear of catching the disease.

The empire’s plans to take back land in the West stopped. Justinian had recently won back parts of North Africa and Italy from the Vandals and Ostrogoths.

He hoped to rebuild the old Roman Empire, but the plague made it impossible to send new soldiers, collect taxes, or hold on to faraway lands.

In Italy, the war against the Goths went on much longer than expected, partly because the plague had reduced the number of soldiers.

Even though he became sick, Justinian survived. According to sources, he left public life while he got better but started ruling again after his illness.

His government tried to keep things running, but many local officials had died, and local government in smaller cities fell apart.

Some superstitious people blamed the emperor or thought the plague was punishment from God.

There were more religious marches and prayers, and some people turned to simple living and preached about the end of the world.

How often the Plague of Justinian returned

The plague did not go away after the first outbreak. It came back in waves for more than two hundred years, hitting the empire again and again between AD 541 and the early 8th century.

Each new outbreak killed more people, making it harder for the Byzantines to keep control of their outer regions.

The long-term loss of people meant less tax income, weaker armies, and greater danger from outside threats.

In the 7th century, Arab Muslim forces took over large parts of Byzantine land, including Egypt and Syria.

Historians believe that the damage caused by the plague helped explain why the empire could not stop these attacks.

The Plague of Justinian was the first recorded pandemic of bubonic plague. Its return over the centuries led to long-term economic slowdown and military weakness in the Byzantine world.

Even though the empire lasted nearly another thousand years, the plague permanently reduced its strength.

It stopped Justinian’s goal of bringing back Roman greatness and left the population of the eastern Mediterranean much smaller for generations.

The pandemic also affected later changes in medicine and city planning. Doctors at the time did not understand germs and many treatments used religious rituals, lucky charms, or herbal cures that did not work.

Because traditional medicine failed during the crisis, people slowly began looking for better ways to stop and treat disease.

Cities hit by the plague began trying basic public health ideas, like clearing waste and keeping sick people apart, though more effective changes would not happen until much later.

Despite these efforts, the Byzantine government's response to the plague was largely reactive rather than proactive.

There was no understanding of how the disease spread, and thus no effective measures to control it.

Quarantine, a common response to disease outbreaks today, was not widely practiced. The government's ability to provide relief was also limited by the economic strain caused by the plague and ongoing military campaigns.

Although the initial outbreak in 541–544 was the most devastating, the plague returned in waves for the next two centuries, periodically crippling the Byzantine Empire until its disappearance around 750.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.