The 15 most famous sites at Pompeii

In the shadow of Mount Vesuvius lies a famous city that was frozen in its final moments almost 2000 years ago. Now, it is known for its vibrant frescoes, intricate mosaics, and hauntingly familiar remnants of daily life that make us want to listen to their whispered stories of an extraordinary past.

Many of Pompeii’s streets are now uncovered once more and are lined with ancient ruins of grand temples and bustling marketplaces.

Each corner reveals a new wonder, from luxurious villas decorated with exquisite art to public baths that still echo with the memories of the last people to have used them.

This once-thriving city, silenced by ash and time, now draws visitors from all over the world with its remarkably preserved treasures.

If you plan to visit, here are the most incredible sites you should not miss while there.

1. The Forum: The Heart of Public Life

Perhaps the most important location in the entire city of Pompeii was the forum. It was the center of civic, religious, and economic life.

This broad, open, rectangular area was surrounded by grand columns, which provided a hub where citizens gathered for daily activities and a range of important events.

It was built during the second century BCE and, over the decades, was lined with temples, basilicas, and various public buildings.

The forum’s layout indicates its importance, with its prime position next to one of the main gates and its accessibility from major streets.

The forum became the place where local officials addressed public matters. Political assemblies occurred here, where magistrates issued proclamations, and the townspeople learned of new laws and administrative decisions.

The largest structure in the forum was the basilica, which is still situated on the forum’s western edge.

It housed courts where legal disputes were resolved, and commercial transactions were managed.

It boasted a vast interior and rows of columns and provided an imposing formal setting for the public enforcement of Roman law.

Economically, the forum functioned as a bustling marketplace where merchants displayed their goods and conducted trade.

The macellum, or market building, located along the eastern side, contained a series of stalls that catered to shoppers seeking fresh produce, fish, and other essential goods.

On most days, artisans and store vendors created a lively atmosphere of commerce and exchange.

There may have been public granaries as well, including the horrea, were situated nearby, which were designed to ensure that the city’s food supply remained secure and accessible.

2. The Amphitheater: Entertainment and gladiators

Completed in 70 BCE, the amphitheater at Pompeii was the oldest surviving Roman amphitheater.

We still know the name of its designers: Gaius Quinctius Valgus and Marcus Porcius.

It was constructed with the support of prominent magistrates, and it was located on the outskirts of the city, where its massive elliptical design accommodated approximately 20,000 spectators.

This number far exceeded Pompeii’s actual population, which indicated that the amphitheater also drew crowds from the city’s surrounding regions.

The amphitheater was designed for gladiatorial combat and other grand spectacles.

Such gladiators were often enslaved people or prisoners of war who trained rigorously to perform in these events.

Crowds gathered to witness combat between gladiators or battles against wild animals brought from across the empire.

On significant occasions, the amphitheater became the site of elaborate events that blended entertainment with displays of Roman authority.

Public games, usually funded by wealthy benefactors or local magistrates, would reinforce social order by offering the populace a venue for communal enjoyment while emphasizing the power of the elite.

These events were known as munera, and they provided regular opportunities for political figures to gain favor with the public through acts of generosity.

3. The House of the Faun: Pompeii's grandest residence

Of all the houses in the city, one of the most famous is known as the House of the Faun.

It appears to have been originally built during the second century BCE, and was so large that it spanned an entire city block in Pompeii.

This luxurious residence, which was one of the largest in the city, featured a layout that combined public and private spaces.

Its construction followed the Roman domus model, with atria and peristyles arranged to create a series of interconnected courtyards and living areas.

The central atrium was the focal point of the house and included an impluvium that collected rainwater.

The house also had multiple tablinums and triclinia, which provided areas for formal gatherings and dining.

Inside the house, a series of elaborate mosaics adorned many floors. These were meant to show off the wealth and cultural sophistication of its owners.

The most famous example, the Alexander Mosaic, was located in the exedra of the second peristyle, which was a grand reception area.

It measured approximately 5.82 by 3.13 meters and depicted a dramatic scene of either the Battle of Issus or Gaugamela.

The artwork showed Alexander the Great charging on horseback toward the Persian king Darius III, who was fleeing in his chariot.

The mosaic used tesserae, which were small, individually cut pieces of colored stone, and allowed for remarkable detail and realism.

The house of the faun also displayed evidence of a biclinium, which was a dining space with two couches arranged for reclining guests.

This feature, combined with the multiple gardens and water features found throughout the property, highlighted the importance of leisure and luxury in the lives of its occupants.

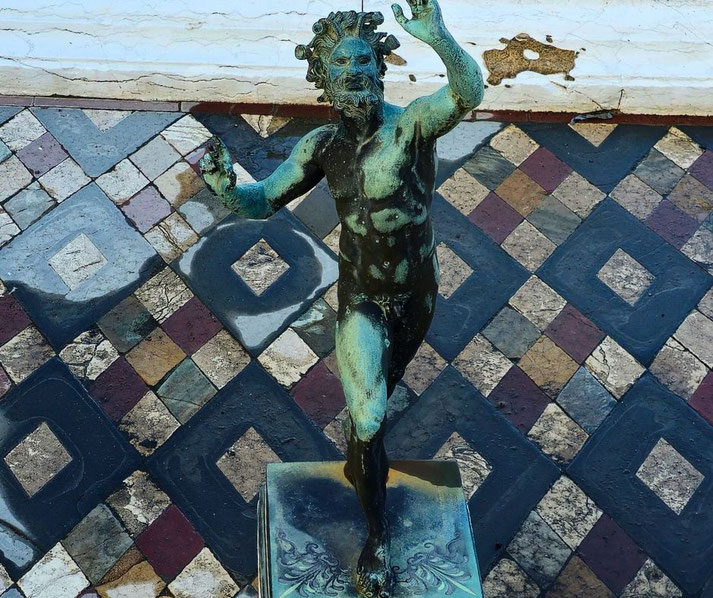

Excavations of the house also revealed fragments of statuary, including the small bronze faun after which the residence was named.

It was positioned in the center of the impluvium, and the statue depicted the mythological figure in a dynamic pose of dance.

4. The Villa of the Mysteries: Fascinating frescoes

Situated on the outskirts of Pompeii, the Villa of the Mysteries is now famous for its remarkably preserved frescoes, which adorned a triclinium located in the northwestern section of the estate.

This luxurious building was originally constructed in the second century BCE, but underwent several renovations just before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

The frescoes were discovered during excavations in 1909. Analysis shows that they were painted using the fresco secco technique, which involved applying pigments onto dry plaster.

This allowed the Romans to use vibrant colors and intricate details which has endured very well over centuries.

Inside the triclinium, the frescoes formed a continuous frieze along the walls, depicting scenes interpreted as initiation rites into the cult of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and ecstasy.

The imagery included larger-than-life figures participating in rituals, including a woman receiving a sacred veil and another being whipped by a winged figure.

Each character is rendered with extraordinary precision in a way that still conveys motion and emotion through dynamic poses and expressive faces.

The central figure of Dionysus, reclining alongside Ariadne, appeared surrounded by his retinue, which included satyrs and maenads.

Specifically, the use of perspective and shading gives the scenes a three-dimensional quality, which enhances their dramatic impact on those that view them.

Archaeologists also found evidence suggesting that the villa of the mysteries supported a thriving agricultural operation, including the production of wine.

Large storage jars, or dolia, were uncovered in the surrounding fields, which were part of the villa’s economic activities.

These findings suggest a direct connection between the Dionysian imagery and the villa’s role in viticulture.

Ultimately, the villa of the mysteries offers a rare but important glimpse into the private lives and spiritual practices of Pompeii’s elite.

5. The Temple of Apollo: A religious landmark

While not the largest religious building in the city (that honor is held by the Temple of Jupiter), the temple of Apollo was probably one of the most significant structures in Pompeii.

It is situated on the western side of the forum, which meant that it occupied a prominent position in the city.

Archaeological evidence suggests the temple was originally constructed in the 6th century BCE, with later renovations during the Roman period.

Measuring approximately 25 meters in length, the temple featured a high podium, which elevated it above the surrounding area.

A peristyle of 48 ionic columns enclosed a rectangular courtyard in the temple and were constructed from tufa and later faced with stucco.

When completed, it provided an elegant frame for the sanctuary of the temple and a shaded area for worshippers.

At the center of the courtyard was a marble altar facing the temple’s entrance, where sacrifices and offerings were made to Apollo.

Inscriptions discovered near the altar indicate that these rituals were performed quite regularly, such as the Ludi Apollinares held in Apollo’s honor.

Inside the temple’s cella, or inner chamber, stood a bronze statue of Apollo, which depicted him as an archer.

Another statue, representing his sister Diana, was also found in the vicinity. The artistic details of these statues, including their flowing drapery and lifelike expressions, demonstrated the combination of Greek aesthetic principles with Roman tastes.

6. The baths of Pompeii: Social and hygienic hubs

Situated near the forum, the Stabian Baths were among the largest and most elegant bathing complexes in Pompeii.

They covered an expansive area of approximately 3,500 square meters. These facilities were divided into sections for men and women, and included a series of interconnected rooms such as the frigidarium, tepidarium, and caldarium.

These rooms were designed to provide a progression of temperatures for the bathing process.

The central courtyard, surrounded by colonnades, was a palaestra where visitors could exercise before bathing.

The caldarium, in particular, featured vaulted ceilings and a large bronze brazier, which was used to heat the water.

Its walls were adorned with stucco reliefs that depicted mythological scenes.

Meanwhile, the tepidarium boasts marble benches that line the room, which was intended to provide a space for relaxation between hot and cold baths.

The frigidarium was equipped with a circular cold-water pool and offered a refreshing conclusion to the bathing ritual.

Motivated by the need for communal hygiene and social interaction, the baths became essential to daily life in Pompeii.

Citizens from various social classes gathered here to cleanse themselves, conduct business, or simply socialize.

The structured environment encouraged mingling because it created a space where civic relationships were strengthened.

Thanks to the affordability of access, even lower-income individuals could use the baths.

As a consequence of their centrality to Pompeian life, the baths also reflected the city’s economic prosperity and cultural sophistication.

The second complex, known as the Forum Baths, were constructed during the 1st century BCE, and offered a smaller but equally refined alternative to the Stabian Baths.

They featured similar facilities, including a tepidarium with decorative plasterwork and a well-preserved caldarium with a niche for water heating.

Their proximity to the forum would have meant that they attracted a steady flow of patrons who sought both leisure and cleanliness.

7. The Lupanar: Insights into Pompeii’s red-light district

This is the most notorious location in Pompeii. The Lupanar is located on a somewhat ‘quiet’ street.

It was a brothel, and was one of the few explicitly designated for prostitution. It was a relatively small building, but featured a cubicula arranged around a central corridor.

Each room of the building contained a single stone bed, which would have been covered with a staw mattress for use by clients.

The word lupanar, derived from the Latin ‘lupa’, meaning she-wolf, which referred to both the establishment and its workers.

Inside, the top of the walls were painted with very explicit frescoes which illustrated various sexual acts.

Typically, children are not allowed into this building while visiting the ruins of the city.

However, for the Romans, these illustrations would have been a ‘menu’ of services available, which would have been especially useful for those who struggled with the language barrier.

Alternatively, they may have added an element of anonymity for clients by allowing them to indicate preferences without verbal communication.

The Lupanar also contained a number of inscriptions, or graffiti, which revealed personal details about its visitors and workers.

They were carved directly into the walls and ranged from humorous remarks to expressions of affection.

One such inscription read, “I came here and had a good time,” while others included names and references to the women who worked in the establishment.

These texts provide a rare and intimate perspective on the individuals who frequented the brothel, which offers a humanizing view of a space often reduced to its functional role.

8. The House of the Tragic Poet: Art and elegance

Situated in a prominent area near Pompeii’s forum, the house of the tragic poet was renowned for its exquisite mosaics and frescoes.

Despite its relatively modest size compared to other elite residences, the house was richly decorated.

This suggests that its occupants prioritized artistic refinement over sheer grandeur.

At the entrance, the famous Cave Canem mosaic depicts a black dog accompanied by the warning "Beware of the Dog", greeted visitors.

This detailed mosaic was crafted from thousands of tesserae.

Beyond the entrance, the atrium boasted elaborately painted walls and intricate floor mosaics, including mythological scenes, such as depictions of the Trojan War.

The tablinum has a notable mosaic that portrays a theatrical performance, which was a recurring theme in Roman art.

This piece has inspired the modern name of the house. The careful arrangement of tesserae in the mosaics created a sense of depth and movement.

Also, the peristyle garden at the rear of the house contains a small fountain that was bordered by painted walls that depicted pastoral landscapes.

9. The Temple of Jupiter: Dominating the forum

The most prominent religious structure in Pompeii was the temple of Jupiter, which is found at the northern end of the forum.

Dating from the 2nd century BCE, this grand temple was dedicated to the chief deity of the Roman pantheon, Jupiter Optimus Maximus, who was revered as the protector of Rome and its territories.

Its elevated podium, which can still be seen, measured approximately three meters in height.

This meant that it created a commanding view over the forum and allowed worshippers to ascend a flight of steps to reach the sacred space.

The temple housed an imposing statue of Jupiter, which was crafted from a combination of stone and precious materials.

The statue depicted the god in a seated pose, holding a thunderbolt. Flanking him were smaller statues of Juno and Minerva, who formed part of the Capitoline Triad, were also richly adorned.

Structurally, the temple featured a hexastyle façade with six Corinthian columns, which supported a triangular pediment decorated with sculptural reliefs.

Like the Temple of Apollo, the columns of this temple were constructed from tufa and later covered with stucco.

The temple’s roof was originally tiled with terracotta, and fragments discovered during excavations suggested it was decorated with ornamental antefixes depicting mythological scenes.

Public religious rituals held to honor Jupiter often took place on the large altar situated in front of the temple, where sacrifices were made to seek the god’s favor.

These gatherings would have been organized by the wealthy local magistrates who were responsible for overseeing religious affairs.

10. The Garden of the Fugitives: A somber reminder

On the southern edge of Pompeii you can find the Garden of the Fugitives. This is one of the most emotive places in the city, because it offers a somber glimpse into the final moments of those who attempted to escape the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

This area was originally an agricultural plot and it contained the preserved plaster casts of 13 individuals who were overwhelmed by the pyroclastic flow that swept through the city.

The victims, who were likely families and laborers, sought refuge in the open space, as they probably believed it would provide safety from the falling debris.

Instead, the intense heat and toxic gases claimed their lives, leaving behind haunting impressions of their final positions.

Archaeologists created the casts using a technique pioneered by Giuseppe Fiorelli in the 19th century.

Plaster was carefully poured into voids left in the hardened volcanic ash, which preserved the shapes of the victims’ bodies.

This method revealed extraordinary details, including facial expressions, clothing folds, and even the positioning of fingers and limbs.

One cast showed a man who was crouched protectively over a child, which suggested a desperate attempt to shield them from harm.

The garden measured approximately 36 by 27 meters, and still contained remnants of its original agricultural use, including traces of ancient planting beds.

By analyzing soil composition and preserved botanical remains, researchers identified grapevines and other crops cultivated in the area.

Modern visitors to the Garden of the Fugitives encountered not only the physical remains of the victims but also interpretive displays that contextualized their final moments.

11. The Bakery of Modesto: A glimpse into Roman cuisine

Situated in Pompeii’s bustling commercial district, the bakery of Modesto (or Modestus), otherwise known as the bakery of Popidius Priscus, has become one of the most important sites about the food production and daily routines of Roman society.

This bakery has identified by an inscription bearing the name of its owner, and was among more than 30 bakeries uncovered in the city.

Its layout included a central workspace, storage areas, and a shopfront, which would have provided direct access to customers as they passed by in the street.

The presence of four large millstones, which were powered by animals or manual labor, show the remarkable industrial scale of flour production.

Millstones like these were carved from volcanic basalt, which was ideal for grinding grain into the fine flour used in breadmaking.

Inside the bakery, archaeologists discovered a brick oven measuring approximately two meters in diameter, which included a dome-shaped chamber and a venting system that allowed for consistent heat distribution.

Historians estimate that the bakery could produce hundreds of loaves daily, suggesting that it catered not only to private households but also to local taverns and street vendors.

The recovery of carbonized loaves, known as panis quadratus, revealed details about Roman breadmaking, including the use of segmented molds to portion the dough.

Adjacent to the production areas, the bakery included a counter with embedded storage jars (dolia), which were used to display and sell baked goods.

Customers likely purchased bread directly from this counter. The strategic location of the bakery near major thoroughfares ensured a steady flow of patrons, which supported its economic success.

Wooden paddles, scales, and measuring vessels were found on this site. These would have last been used by Popidius Priscus, the proprietor, his family or enslaved workers, who managed the daily operations.

12. The Streets of Pompeii: Cobblestones and carved grooves

The many streets that criss-cross the ancient site of Pompey were surprisingly carefully planned and meticulously constructed.

They were designed with simple cobblestones crafted from volcanic basalt. The roads do vary in width, with larger streets accommodating carts and foot traffic, while narrower alleys connected residential areas and allowed only pedestrians.

The smooth, rounded surfaces of the cobblestones still show signs of extensive use, including grooves carved by the repeated passage of wooden cart wheels.

Some of these grooves measure several centimeters in depth in some places, which demonstrates the frequency of trade and transportation within the city.

However, strategically placed stepping stones allowed pedestrians to cross larger streets without stepping into water or waste, which frequently collected during rainstorms or as a result of daily cleaning.

These large, flat stones, set at intervals across the road, were intentionally elevated to match the height of the sidewalks.

This was done in a way that the spaces between the individual blocks were carefully aligned to accommodate the width of the wheels of carts, which balanced the needs of sanitation and mobility.

Alongside the streets, a network of street-side shops, known as tabernae, provided goods and services to Pompeii’s bustling population.

These small commercial spaces were often integrated into the ground floors of larger residential buildings, which allowed property owners to benefit from rental income.

The various shopfronts typically featured wide openings with wooden shutters, which could be slid open, removed, or secured as needed.

Archaeological evidence show that counters with embedded dolia and frescoes advertising wares allowed businesses to attact customers as they passed by.

In some regions of the city, bakers, wine merchants, and cloth dyers all operated within close proximity with each other.

At the crossing of many streets, you can find public fountains and water troughs.

These were built by the Romans to ensure ready access to fresh water for residents and animals.

They were fed by an advanced aqueduct system which was constructed from durable materials such as tufa and marble.

13. The House of the Vettii: Luxurious living and decadent art

Completed during the first century CE, the house of the Vettii was a remarkable example of opulence and artistic refinement in Pompeii.

It was owned by two wealthy freedmen, Aulus Vettius Conviva and Aulus Vettius Restitutus.

They wanted their grand residence to be a public showcase of their rise to social prominence through heavy investments in its elaborate decoration and design.

As a consequence, the house featured an atrium with an impressive impluvium, which collected rainwater, and multiple rooms adorned with frescoes that represented the Fourth Style of Roman wall painting.

The frescoes combined intricate architectural motifs and vivid mythological scenes.

Inside the triclinium, or dining room, more frescoes depicted scenes from Greek mythology, including the punishment of Ixion and the labors of Hercules.

These images were crafted with a meticulous attention to detail, using deep reds, blues, and golds to create a dramatic contrast.

Modern historians believe that the themes chosen for the frescoes, which frequently illustrated tales of divine justice or triumph, were meant to reflect the owners’ aspirations to align themselves with heroic and divine figures.

If so, this artistic program were hoped to impress guests and reinforce the status of the Vettii brothers in Pompeian society.

Tourists are often impressed by the peristyle, a colonnaded courtyard located at the centre of the house.

It is surrounded by frescoed walls depicting lush garden landscapes, and a series of marble fountains and statues added to its serene atmosphere.

Adjoining the peristyle was the lararium, or household shrine, which was decorated with frescoes of the household gods, or Lares.

As such, the peristyle into both a functional space for social gatherings and a visual statement of wealth.

14. The Fullery of Stephanus: How Romans washed clothes

One of most curious buildings in Pompeii is a fullery: one of the largest fullonicae ever discovered.

It was owned by a man called Stephanus and it was a kind of professional cleaning service that specialized in laundering and finishing garments.

The building’s purpose was deduced from a spacious atrium that contained large basins made of tufa, which were used for washing textiles.

In them, workers manually agitated the garments in these basins using their feet.

This was a process that was labor-intensive yet essential for thoroughly cleaning the fabrics.

Next to the atrium are several smaller rooms that served their own specific purposes, including dyeing and pressing garments.

In one corner, a press with a sturdy wooden frame was used to shape and smooth the fabric after cleaning.

The press created sharp pleats and folds. The presence of amphorae containing oils and fuller’s earth, a fine clay used for cleaning, indicated the advanced techniques employed to achieve professional results.

Above the ground floor, a mezzanine level provided living quarters for Stephanus and his workers.

This space was accessible by a narrow staircase and was modest in comparison to the bustling workshop below.

The proximity of the living and working areas is a typical demonstration of the integration of commercial and domestic life in Roman cities.

Interestingly, inscriptions found on the walls in this house, including advertisements for the fullery’s services that frequently referenced the quality of the work and the satisfaction of previous customers.

At the rear of the building, visitors can find an open courtyard that contained large vats for soaking fabrics, which complemented the operations in the atrium.

This outdoor area allowed for better evaporation of moisture as well as the application of natural sunlight to bleach textiles.

The strategic design of the courtyard permitted efficient airflow, which may have caused problems for the smell in a densely populated urban setting.

Importantly, the presence of an adjacent cistern ensured a constant water supply, which was critical for the washing and dyeing processes.

15. The Theatres: Home of dramatic performances

Located in the southern part of Pompeii, a pair of theatres were the vibrant centers of entertainment for the city.

The larger of the two, the Great Theatre, was built in the 2nd century BCE and could accommodate approximately 5,000 spectators.

This semi-circular theatre featured a cavea, or seating area, which was divided into sections by social rank.

The marble-clad ima cavea was closest to the stage and was reserved for the elite, while the upper sections housed the general populace.

It appears that the theatre's impressive acoustics, achieved through careful design and construction, ensured that performances could be heard clearly by all attendees.

Adjoining the Great Theatre, the smaller Odeon provided a more intimate venue for musical performances and poetry recitals.

This was dates from around 80 BCE and had a capacity of approximately 1,500 people.

The roofed design of the Odeon was supported by wooden trusses. This helped to enhance the acoustics and protected the audience from the weather.

Its layout included a well-preserved orchestra area, which was used by performers and musicians, and a raised stage, or pulpitum, that allowed actors to engage directly with the audience.

At the heart of the theatrical experience was the scaenae frons, the elaborately decorated backdrop of the stage, which was an important element in creating a visually striking element to performances.

It included columns, niches, and statues to create a sense of grandeur while also framing the actors' movements.

In the Great Theatre, the scaenae frons stood approximately two stories high, while the stage itself was made of wood and extended outward.

This allowed the performers to engage with the audience more directly.

Access to the theatres was facilitated by a network of entrances and exits, or vomitoria, which ensured the efficient movement of large crowds.

These passageways connected the seating areas to the external streets. It appears that they were effective in reducing congestion for spectators.

There have been inscriptions and graffiti found on the walls near the theatres.

They have provided rare evidence of the types of performances held, including comedies, tragedies, and pantomimes, and referenced prominent actors and producers, suggesting that the theatrical scene in Pompeii attracted notable talent.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.