The Res Gestae: Emperor Augustus’ most shameless form of self-promotion

The very first Roman emperor, Augustus, never did anything by half measures. He is most famous for transforming Rome from a crumbling republic into a glittering empire, but to do this, he hoarded power behind a mask of humility, and even dictated how history should remember him.

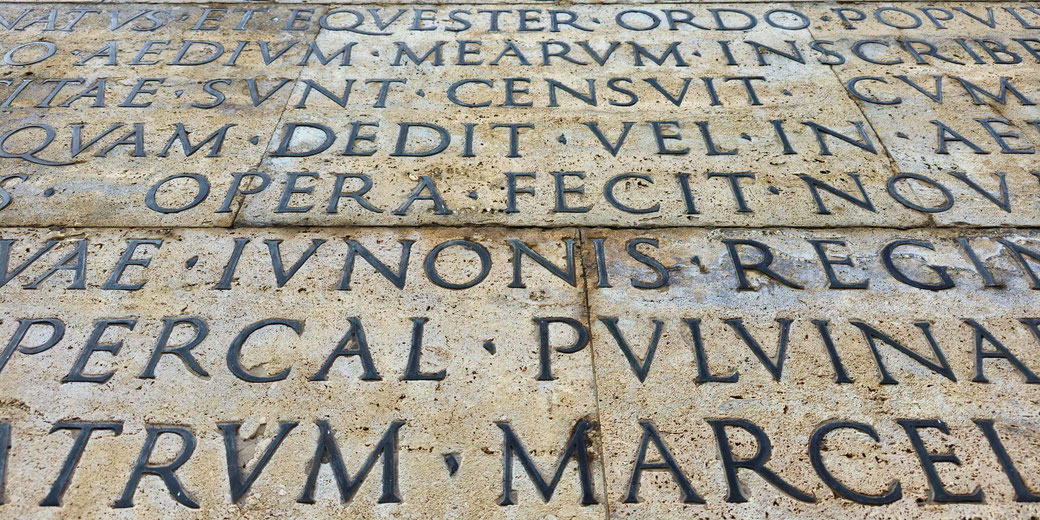

The most powerful record of his achievements is known as the Res Gestae Divi Augusti and Augustus had it inscribed on bronze tablets to be copied across the empire to ensure that no one forgot who built Rome’s golden age.

This meant that his version of events was polished, flattering, and carefully designed to outlive him.

What is the Res Gestae Divi Augusti?

The Res Gestae Divi Augusti, which means ‘The Deeds of the Divine Augustus’, was a formal record of Augustus' achievements, which was displayed publicly after his death in 14 AD.

The Latin title emphasized his status as a deified ruler, which meant that his actions were not considered to be just political accomplishments but events of lasting significance.

Specifically, the document detailed his military campaigns, political reforms, and financial generosity, which were presented as proof of his exceptional leadership.

His words framed his reign as one of service rather than domination, which was a deliberate strategy to maintain the image of a ruler who restored order rather than seized control.

Because Augustus carefully controlled his legacy, the Res Gestae was structured to highlight his contributions in a way that reinforced his authority.

The text was divided into sections that covered military victories, civic improvements, financial donations, and public honors.

He described himself as princeps, the first citizen, which was a deliberate way to reinforce the idea that he had led the Roman people without ruling as a king.

The absence of any mention of the civil wars that had brought him to power, which had seen the destruction of his rivals and the execution of political enemies, showed how carefully he framed his narrative.

He presented his rise as a natural and necessary event.

What Augustus wanted future generations to remember

Because military success was central to Roman authority, Augustus devoted a significant portion of the Res Gestae to his conquests, which reinforced his image as a victorious leader.

He listed the provinces he had secured, the foreign rulers who had submitted to him, and the campaigns he had funded.

His phrasing suggested that Rome expanded not through aggression but through his ability to bring order to unstable regions.

He mentioned his victories over the Cantabrians in Hispania, the Alpine tribes, and the Parthians, who returned the Roman standards lost by Crassus at Carrhae in 53 BC.

Since political stability had been uncertain before his rise, Augustus emphasized the legal and structural reforms that allowed him to consolidate control.

He mentioned the powers granted to him by the Senate, which included imperium proconsulare maius and tribunicia potestas, which meant that he could overrule governors and intervene in civic matters without holding an official magistracy.

His careful wording suggested that he maintained the Senate’s influence, which was a necessary reassurance to the aristocracy, even though his control over the army and administration ensured that no real opposition could threaten his rule.

Public generosity was a key element of Roman leadership, so Augustus recorded his financial contributions in great detail, which reinforced his role as the benefactor of the Roman people.

He listed the number of denarii distributed to the plebeians, the number of colonies he founded for veterans, and the festivals he funded, which included extravagant gladiatorial games and theatrical performances.

He described the reconstruction of temples, which included the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine and the completion of Julius Caesar’s Forum.

However, his focus on public spending, which suggested generosity rather than necessity, obscured the fact that much of this wealth had come from the spoils of war and personal confiscations during the civil wars.

How and where was it displayed?

The Res Gestae Divi Augusti was originally inscribed on bronze tablets, which were displayed outside the Mausoleum of Augustus.

This imposing structure was built on the Campus Martius and was designed as both a tomb and a monument to his achievements.

The location ensured that citizens could read the inscription and be reminded of his contributions to Rome.

Sadly, the original tablets no longer survive, but they would have presented his words in large, formal lettering, which was a common practice for official inscriptions meant for public reading.

Throughout the empire, copies of the Res Gestae were displayed in provincial cities and were carved into stone rather than cast in bronze.

In the western provinces, where Latin was the dominant language, the text would have been inscribed without translation.

Meanwhile, in the eastern provinces, where Greek was more widely understood, bilingual inscriptions were produced, which meant that local populations could read and interpret the message.

The placement of these copies, which were often found in temples or public forums, ensured that his words reached local elites, who played a crucial role in maintaining imperial authority in distant territories.

Among the surviving copies, the Monumentum Ancyranum in Ankara, which was ancient Ancyra, remains the most complete.

This inscription was carved into the temple of Rome and Augustus. It preserves both the Latin and Greek versions, which allows modern historians to study how the text was presented to different audiences.

Other fragments of the Res Gestae have been found in Apollonia and Antioch in Pisidia, and these confirm that similar inscriptions were placed in other cities.

Nowadays, a reconstructed version of the text can be found on the outside wall of the museum of the Ara Pacis in Rome.

Can we trust Augustus’ own version of history?

Because the Res Gestae Divi Augusti was written as a first-person account, its reliability depended on the extent to which Augustus controlled its narrative.

He described his achievements in a formal and measured style, which created the impression of an objective historical record.

The structure of the text, which presented his actions as a chronological series of accomplishments, reinforced this sense of factual accuracy.

However, the absence of any mention of his opponents, which included Mark Antony and Sextus Pompey, indicated that he carefully shaped the content to suit his political image.

The document presented his rise to power as the natural outcome of his virtues, which meant that he ignored the bloodshed and political maneuvering that had defined his early career.

Since Augustus controlled the contents of the Res Gestae, his brief allusions to the civil wars only emphasized his role in restoring order, which meant that he provided no details about the battles fought against fellow Romans.

Instead, his references to military victories, which included campaigns in Spain, Gaul, and the East, framed them as defensive actions rather than conquests.

But what did the Romans historians themselves say about the first emperor and his rise to power?

The historian Tacitus, who wrote during the early second century AD, described Augustus as a ruler who secured power through force but maintained control through carefully managed public messaging.

Likewise, Suetonius, who wrote in the early second century AD, recorded both Augustus' achievements and his personal flaws, which included his manipulation of political opponents.

In contrast, Velleius Paterculus, who wrote during the reign of Tiberius, offered a more favorable account, which suggested that his position within the imperial administration influenced his portrayal of Augustus.

As a result a result of the fact that Augustus carefully managed his image, later emperors followed his model to reinforce their authority.

Since he presented himself as princeps rather than a monarch, this led to a tradition in which future emperors avoided titles that suggested kingship, even though they exercised absolute power.

Tiberius, who succeeded Augustus in 14 AD, maintained the outward appearance of Senate cooperation, which helped stabilize his transition.

Later emperors, including Vespasian and Trajan, imitated Augustus' practice of recording achievements in inscriptions.

Following this, emperors often claimed to restore order and act on behalf of the Roman people, such as the Deeds of the Divine Vespasian and the Achievements of Septimius Severus, which followed Augustus’ format.

Later rulers, including Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius, commissioned inscriptions that listed their accomplishments in a similar structure.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.