The ancient Roman history of London

Beneath the bustling streets of modern London lies a history that stretches back to the Roman Empire. Londinium, as it was known, emerged as a vital hub of trade, culture, and dominance, shaping the city's destiny from its very inception.

We will delve into the origins of London, exploring how Roman innovations, from majestic structures to military power, laid the foundation for one of the world's most iconic cities.

The area of London before the Romans

Before the arrival of the Romans, the area that would become London was inhabited by Celtic tribes, with evidence of human activity dating back to the Bronze Age.

Around 1000 BC, the region saw the establishment of a series of small villages and farmsteads, nestled along the Thames River.

These early settlements were primarily agricultural, relying on the fertile lands and abundant resources provided by the river.

By the Iron Age, around 500 BC, the area saw the emergence of more sophisticated settlements, with hill forts and defensive structures indicating a need for protection and organization.

One of the most notable pre-Roman settlements in the vicinity of London was the oppidum at Colchester, believed to have been the capital of the Trinovantes tribe.

This settlement was a significant center of trade and commerce, with connections to other parts of Britain and the continent.

The presence of such settlements suggests a well-established network of communities in the region, each with its own distinct culture and social structure.

The arrival of Julius Caesar's Roman forces in 55 BC and again in 54 BC marked the beginning of a new era for the region.

Although Caesar's expeditions were brief and did not lead to immediate Roman occupation, they paved the way for future conquests.

Why did Rome create Londinium?

The Roman conquest of Britain began in earnest in AD 43 under the command of Emperor Claudius.

The Roman army, led by General Aulus Plautius, crossed the Channel and landed in Kent, facing resistance from local tribes but ultimately proving victorious in a series of battles.

The Romans quickly established a beachhead and began advancing westward and northward.

By AD 47, the Romans had secured control over much of southeastern Britain, including the area that would become London, known as Londinium.

Established around AD 47-50, shortly after the Roman conquest, Londinium was strategically located on the north bank of the Thames River.

The site was chosen for its proximity to the river's estuary, facilitating trade and communication with the continent, and for its defensible position, protected by higher ground to the north and the river to the south.

Londinium began as a small settlement, but its strategic importance quickly became apparent.

The Romans constructed a bridge across the Thames, the first of its kind in the area, which transformed the city into a vital transportation hub.

This bridge, combined with the city's location at the nexus of several key Roman roads, ensured that Londinium became a bustling center of trade and commerce.

Goods from across the Roman Empire, including wine from Gaul, pottery from Italy, and luxury items from the far reaches of the empire, flowed through the city.

As Londinium grew, it attracted a diverse population of merchants, soldiers, officials, and craftsmen.

The city was laid out in a typical Roman grid pattern, with a forum, basilica, and other public buildings at its center.

The construction of a defensive wall around the city in the late 2nd century further underscored its importance and the need to protect its wealth and inhabitants.

Boudica's burning of London

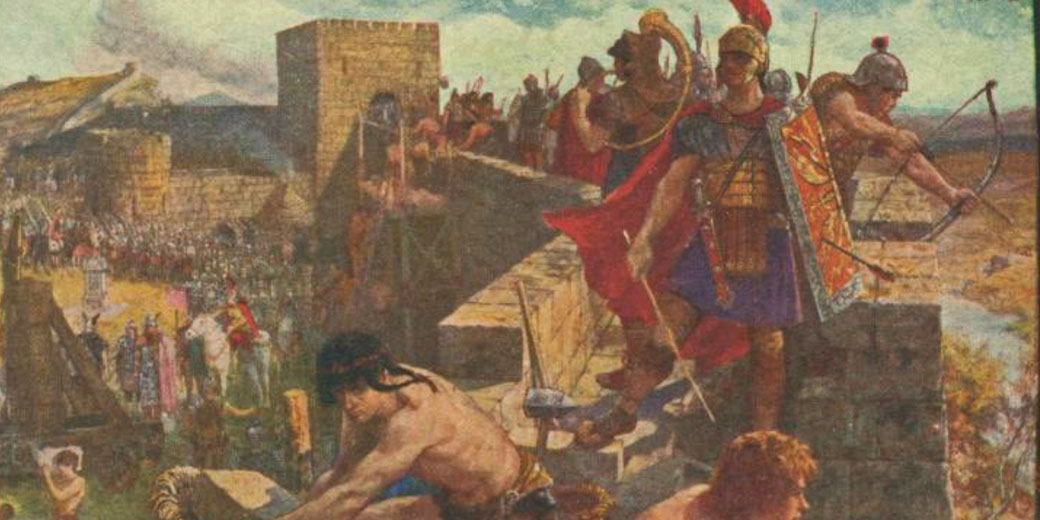

The Boudican Revolt, which occurred around AD 60-61, was a significant event in the history of Roman Britain, with Londinium at the heart of the conflict.

The rebellion was led by Boudica, the queen of the Iceni tribe, who sought to challenge Roman rule following the death of her husband, King Prasutagus.

The Roman annexation of Iceni territory and the mistreatment of Boudica and her daughters ignited the revolt.

Boudica's forces initially targeted Camulodunum (modern-day Colchester), a major Roman settlement and the site of a temple dedicated to the former Emperor Claudius.

After sacking Camulodunum, the rebels turned their attention to Londinium, which had grown into a prosperous trading center and symbol of Roman authority.

The Roman governor of Britain, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, was conducting military campaigns in Wales when news of the uprising reached him.

Realizing the severity of the situation, he marched his forces towards Londinium.

However, upon assessing the city's defenses and the size of the approaching rebel army, he made the difficult decision to abandon Londinium to its fate, prioritizing the preservation of his military forces for a decisive future confrontation.

The rebels entered Londinium and subjected it to a brutal sack. Buildings were torched, inhabitants were massacred, and the city was left in ruins.

The archaeological record reveals a thick layer of burnt debris from this period, a stark testament to the destruction wrought by Boudica's forces.

What happened to London when Rome left Britain?

By the late 3rd century AD, the Roman Empire was facing increasing internal strife and external threats.

Economic difficulties, including inflation and a debased currency, impacted trade and prosperity in Londinium.

The city's population began to decrease, and some areas, particularly those furthest from the city center, were gradually abandoned.

In the early 4th century, the construction of new defensive walls, smaller than the original ones, indicated a contraction of the urban area and a focus on fortification.

This period also saw the rise of Christianity, with the establishment of the first bishop of London in 314 AD, reflecting a significant cultural shift.

The situation worsened in the 5th century as the Roman Empire's hold on its provinces weakened.

In 410 AD, the Emperor Honorius famously told the cities of Britain to look to their own defenses, effectively signaling the end of Roman support.

This left Londinium and other settlements vulnerable to raids by Picts, Scots, and Anglo-Saxon pirates.

The economic and administrative structures that had supported Roman Britain crumbled, leading to further decline in urban life.

By the mid-5th century, Londinium was largely abandoned. The once-thriving city was left in ruins, with its grand buildings falling into disrepair and its streets empty.

The departure of the Roman administration and the breakdown of trade networks left the city a shadow of its former self.

Remarkable archaeological finds from Roman London

One of the most significant finds is the London Mithraeum, a Roman temple dedicated to the god Mithras, discovered in 1954 during the reconstruction of London after World War II.

The temple, dating from the 3rd century AD, is an example of the religious diversity in Roman Londinium.

It has been meticulously restored and is now open to the public, showcasing the religious practices of the time.

Another important discovery is the Roman amphitheater, unearthed in 1988 beneath Guildhall Yard.

Dating back to the 1st century AD, the amphitheater could seat around 6,000 spectators and was used for gladiatorial contests, public executions, and other spectacles.

Its remains highlight the importance of entertainment and public gatherings in Roman urban life.

In recent years, the Bloomberg excavation, conducted between 2010 and 2014, has been one of the most extensive archaeological projects in London.

It uncovered over 14,000 artifacts, including writing tablets, leather goods, and a well-preserved Roman road.

The writing tablets, some of the earliest examples of written Latin found in Britain, have provided invaluable information about the economy, administration, and daily life in Londinium.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.