The Samnites: Ancient Rome's earliest rivals for domination of Italy

Rome, as it rose to dominate the Italian peninsula and the wider Mediterranean world, was not without its rivals. Among these were the Samnites, a group of Italic tribes who fiercely defended their autonomy against Roman expansion.

The story of the Samnites weaves through early Roman history, providing a rich narrative of struggle, resilience, and adaptation.

Theirs is a tale that reflects the complex interplay of power, culture, and identity in ancient Italy.

Origins of the Samnites

Tracing the roots of the Samnites leads us back to the tumultuous early days of the Iron Age in Italy, around the 9th century BC.

They were part of a larger ethnolinguistic group known as the Italic peoples, who migrated into the Italian peninsula from Central Europe.

The Samnites, like their Italic kin, likely brought with them the Indo-European language and culture that would come to shape the development of ancient Italy.

The Samnites were not a singular entity but rather a confederation of tribes including the Pentri, Caraceni, Caudini, and Hirpini.

These tribes shared linguistic and cultural ties, but each maintained a level of autonomy in governance and societal organization.

The process of their unification is not entirely clear and remains a subject of debate among historians.

However, it is widely believed that the tribes formed the Samnite confederation sometime around the 5th century BC, possibly in response to increasing external pressures, particularly from the growing power of Rome.

Where were the Samnites located?

The Samnites were native to a region known as Samnium, situated in the south-central part of the Italian Peninsula.

Today, this area mostly corresponds to the modern Italian regions of Molise and parts of Abruzzo, Campania, and Lazio. Dominated by rugged mountains and fertile valleys, Samnium offered a harsh but fruitful landscape that shaped the lifestyle and culture of the Samnites.

Samnium was bordered by the Apennine Mountains to the north and east, which provided a natural barrier and defensible positions against potential aggressors.

To the west and south, Samnium was bounded by the fertile plains of Campania, the coastal region of the Tyrrhenian Sea, and the Lucanian territories.

This geographic location, set apart yet surrounded by powerful neighbors, was a defining factor in the history of the Samnites.

Samnite society

The Samnites were primarily a tribal society, consisting of several tribes including the Pentri, Caraceni, Caudini, and Hirpini, each with their own regional variations, but bound together by shared cultural and linguistic traits.

The Samnites lived in a balance between nomadic pastoralism, due to the mountainous terrain of their homeland, and settled agricultural life.

Cattle and sheep herding was widespread, as was the cultivation of grain, grapes, and olives.

The society was essentially rural, with most of the population residing in small villages or isolated farmsteads, while a few significant settlements, such as Bovianum, served as administrative and religious centers.

The political structure of the Samnites was somewhat decentralized, reflecting their tribal nature.

Each tribe had its own leadership, which included a council of elders and a chief. However, during times of war, the tribes could unite under a central military command.

Despite their tribal structure, the Samnites developed a degree of political sophistication that enabled them to mount a serious challenge to Rome during the Samnite Wars.

Culturally, the Samnites were part of the broader Osco-Umbrian linguistic group, and they shared many elements of material culture with their Italic neighbors.

Their religious practices likely incorporated elements of animism, ancestor worship, and the veneration of natural features, such as mountains and springs, similar to other ancient Italic peoples.

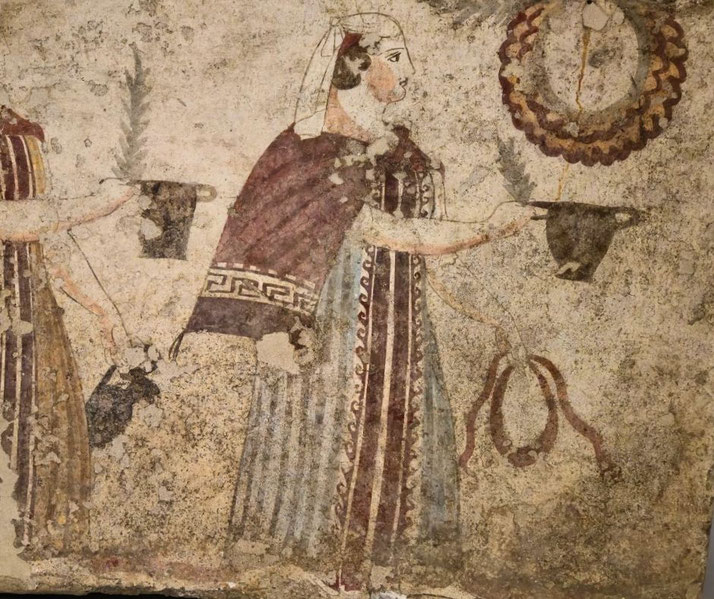

Art and craftsmanship held a special place in Samnite culture. Despite the ruggedness of their lands and the martial character of their society, the Samnites produced delicate and intricate works of art.

This is best demonstrated by the treasures found in the Tomb of the Warrior at Paestum and the bronzes of the Tabula Agnonensis.

These artifacts reveal a society that valued artistic expression and craftsmanship, with influences drawn from the wider Italic and Hellenistic world.

Women in Samnite society also held a relatively high status. This is indicated by the rich grave goods found in female burials, suggesting that women could possess and control their own wealth.

This relatively elevated status of women is a feature found in many pre-Roman societies in Italy.

Interactions with other civilisations

As part of the broader Italic community, the Samnites interacted with several other tribes and civilizations over the course of their history.

These interactions, often marked by conflict but also by periods of cooperation and exchange, played a pivotal role in shaping the cultural, economic, and political landscape of ancient Italy.

The Samnites also had significant interactions with the Greek colonies in Southern Italy, collectively known as Magna Graecia.

As the Samnites expanded southward, they came into conflict with these Greek cities.

This led to the eventual Samnite capture of Capua and Cumae in the late 5th and early 4th centuries BC, respectively.

Despite periods of conflict, there was also cultural exchange between the Samnites and Greeks.

The influence of Greek art, architecture, and religion can be seen in various aspects of Samnite society.

The Samnites, being a part of the larger Italic ethnolinguistic group, interacted frequently with other Italic tribes, such as the Umbrians, Sabines, and the Lucanians.

These interactions were often characterized by both conflict and cooperation, and they played a crucial role in shaping the cultural and political dynamics of the region.

The Samnites had a significant influence on these tribes, especially the Lucanians, who were believed to have broken off from the Samnites.

The most significant of the Samnites' interactions was undoubtedly with the Romans.

The Samnites and Romans had a complex and conflict-ridden relationship. Initially, the two powers managed to coexist, even forming an alliance around 354 BC.

However, as Rome started to expand its influence over the Italian peninsula, clashes became inevitable.

The Samnite military

The military structure and tactics of the Samnites were closely intertwined with their geographical location and cultural ethos.

As a society that was deeply rooted in the rugged landscapes of the central Italian Peninsula, the Samnites developed a military strategy that capitalized on their familiarity with the mountainous terrain and their resilient, warrior culture.

The core of the Samnite military was its infantry, which was renowned for its discipline and tenacity.

These warriors were typically armed with a long spear, or hasta, and a short stabbing sword, akin to the Roman gladius.

This sword would later become a crucial part of Roman military equipment, an indication of the influence the Samnites had on their conquerors.

Each Samnite tribe contributed soldiers to the common military effort, and during the time of war, these tribal contingents could be united under a single command.

However, it's important to note that the Samnites did not have a standing army in the way that the Roman Republic did.

Instead, they relied on levies raised in times of war, a system common among the Italic peoples.

The Samnites' tactics on the battlefield often involved making full use of their homeland's mountainous terrain.

They were adept at ambushes and quick, surprise attacks, making the most of their knowledge of the local geography.

Their defensive strategies also relied on their ability to fortify and defend their hilltop settlements.

One unique aspect of Samnite warfare was the ritualized form of combat known as the Ver Sacrum, or "Sacred Spring." In times of crisis, the Samnites, like other Italic peoples, would vow to dedicate a certain year's offspring, both human and animal, to their gods.

If these dedicated individuals were not required for sacrifice, they would be sent out as a warband to carve out new territories.

A particularly renowned element of Samnite warfare was their armor, which included a large, rectangular shield, bronze helmet, and a linen or bronze cuirass.

This ensemble, particularly the ornate and feathered helmet, became iconic in Roman gladiatorial games, where the "Samnite" was a specific class of gladiator.

This, again, underscores the significant influence the Samnites had on Roman culture, even in the realm of military and public spectacle.

The bitter Samnite Wars against Rome

The Samnite Wars were a series of conflicts fought between the Roman Republic and the Samnites, spanning over half a century from 343 BC to 290 BC.

These wars marked a pivotal phase in Rome's expansion in the Italian Peninsula and were crucial in shaping its future military and political strategies.

The First Samnite War (343-341 BC) was primarily triggered by the Samnites' conflict with the Sidicini, a tribe in Campania, which subsequently led to Rome's involvement.

Despite some Roman successes in the field, the war ended inconclusively due to internal political disturbances in Rome.

The Second Samnite War (326-304 BC) was a more protracted and significant conflict. It started with a dispute over the city of Naples and quickly escalated.

This war saw the Romans suffer one of their most infamous defeats at the Battle of Caudine Forks in 321 BC, where a Roman army was trapped in a mountain pass and forced to surrender.

However, Rome gradually recovered and started employing new tactics, including the construction of roads and fortifications to secure their gains.

By the end of this war, Rome had achieved significant territorial gains, securing much of central and southern Italy.

The Third Samnite War (298-290 BC) was the final and decisive conflict. It saw a broad coalition of Samnites, Etruscans, Umbrians, and Gauls attempting to check Roman expansion.

Despite some early setbacks, the Romans prevailed, largely due to their superior strategy and infrastructure, as well as the inability of the opposing coalition to coordinate effectively.

The decisive Battle of Sentinum in 295 BC, where the Romans emerged victorious against a numerically superior enemy, marked a turning point.

The war ended in 290 BC with the defeat and submission of the Samnites.

The Samnite Wars were not just significant from a military perspective but also from a socio-political one.

They marked the transition of Rome from a regional power to a dominant power in the Italian Peninsula.

These wars also led to crucial changes in the Roman army, leading to the development of the Manipular Legion, a more flexible and versatile military formation which replaced the earlier phalanx system, a transition often attributed to Samnite influences.

Ongoing resistance to Rome

Following their defeat in the Third Samnite War in 290 BC, the Samnites became subjects of Rome.

However, the Samnite state as an independent entity did not end abruptly, nor did the Samnite identity disappear overnight.

Despite being technically under Roman control, the Samnites maintained a degree of autonomy, retaining their local customs and governing structures.

They were classed as 'allies' by Rome, a status that offered a certain level of self-governance, but also required military support for Rome as needed.

The Samnites continued to live in their hilltop settlements, maintaining their pastoral lifestyle, and keeping their language and traditions alive.

However, the relationship between Rome and the Samnites remained tense, and the Samnites continued to resist Roman dominance whenever possible.

They participated in several uprisings against Rome, including the Pyrrhic War (280-275 BC) and the Second Punic War (218-201 BC).

In the latter, the Samnites sided with Hannibal of Carthage, one of Rome's greatest enemies, which further strained their relationship with Rome.

The final blow to the independent Samnite state was the Social War (91-88 BC), also known as the War of the Allies, when Rome's Italian allies, including the Samnites, revolted against the Roman Republic demanding full citizenship rights.

Despite initial successes, the rebels were eventually defeated, primarily due to the Romans granting citizenship to those who remained loyal or surrendered early.

After the Social War, the Samnite territory was fully integrated into the Roman Republic, and the Samnites were granted Roman citizenship.

This move led to increased Romanization of the Samnites as they were progressively assimilated into Roman society.

By the 1st century AD, Latin had largely replaced the Samnite language, and the once-independent Samnite state was reduced to a memory.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.