What was the Roman festival of Saturnalia and how is it linked to Christmas?

The ancient festival of Saturnalia was an annual celebration that turned the structured Roman society upside down, introducing a period of mirth and liberty that blurred the lines between master and servant, rich and poor.

As the winter chill enveloped the city, Romans of all classes eagerly anticipated the onset of festivities, where conventional norms were suspended, and revelry knew no bounds.

But what was the true nature of Saturnalia? How did this festival begin, and what were its main customs?

Did it indeed invert the rigid social hierarchy of Rome, and if so, how?

What impact did Saturnalia have on the Roman calendar, and how does its influence resonate in modern times?

The ancient history of Saturnalia

Saturnalia was focused on the worship of Saturn, the god of agriculture and time.

The festival likely began as a single day celebration, taking place on December 17th of the Julian calendar.

It was initially a time for farmers to mark the end of the autumn planting season with feasting and merriment.

As Rome evolved from a rural society into a powerful empire, so too did the nature and scope of Saturnalia.

By the late Republic period, it had transformed into a multi-day extravaganza, extending to seven days, ending around December 23rd.

Furthermore, Saturnalia's placement in the calendar positioned it in relation to other important Roman festivals.

It followed the Consualia, a festival celebrating the end of the agricultural year, and preceded the Kalends of January, marking the beginning of the new year.

This sequencing of festivals created a prolonged period of celebration during the winter months, offering Romans a respite from their daily labors and an opportunity to prepare for the year ahead.

The evolution of Saturnalia was also influenced by historical events and cultural exchanges.

The inclusion of the Sigillaria, a day for giving small figurines and gifts, likely stemmed from earlier Greek traditions, reflecting Rome's absorption of Greek customs.

Additionally, historical milestones, such as Julius Caesar's reform of the calendar in 45 BCE, which led to the synchronization of the festival with the winter solstice, gave Saturnalia a cosmic significance.

This alignment with the shortest day of the year added a symbolic layer to the festivities, celebrating the rebirth of the sun and the triumph of light over darkness.

Saturnalia's transformation from a farmers' festival to a statewide celebration also mirrored Rome's own transformation.

During the Empire, Saturnalia became an occasion for citizens and rulers alike to participate in a societal inversion.

Emperors like Augustus and Caligula were known to participate, albeit with varying degrees of enthusiasm, underscoring the festival's pervasive appeal and its role in the social fabric of Roman life.

What did the Romans do during Saturnalia?

The celebration of Saturnalia was a time of joy and abandon that enveloped the city of Rome and beyond.

As the festival commenced, normal life came to a halt with businesses, courts, and schools closing their doors, giving way to a period of leisure and festivity.

The public spaces of Rome transformed with vibrant decorations, particularly with greenery like holly and laurel, symbolizing the agricultural god Saturn's connection to renewal and bounty.

At the heart of Saturnalia was the temporary subversion of Rome's rigid social order.

Slaves were granted temporary freedom to speak and act with less restraint, a practice that underscored the festival's theme of liberty and equality.

Feasts were central to the celebrations, with the master-slave roles often reversed; masters would serve meals to their slaves, or everyone would dine together, blurring the lines of social hierarchy.

This role reversal was accompanied by a relaxed dress code, where the formal toga was set aside in favor of the synthesis, a colorful, casual garment.

Gift-giving was another key element of Saturnalia, with presents ranging from wax candles, signifying the light of knowledge, to small terracotta figurines called sigillaria.

These gifts often carried symbolic meanings, sometimes humorous or satirical.

The air of the festival was filled with a sense of freedom, as gambling, normally restricted, became a common pastime, and the streets echoed with the sound of shouts of “Io Saturnalia!” - a jubilant expression of the festive spirit.

The religious elements of Saturnalia

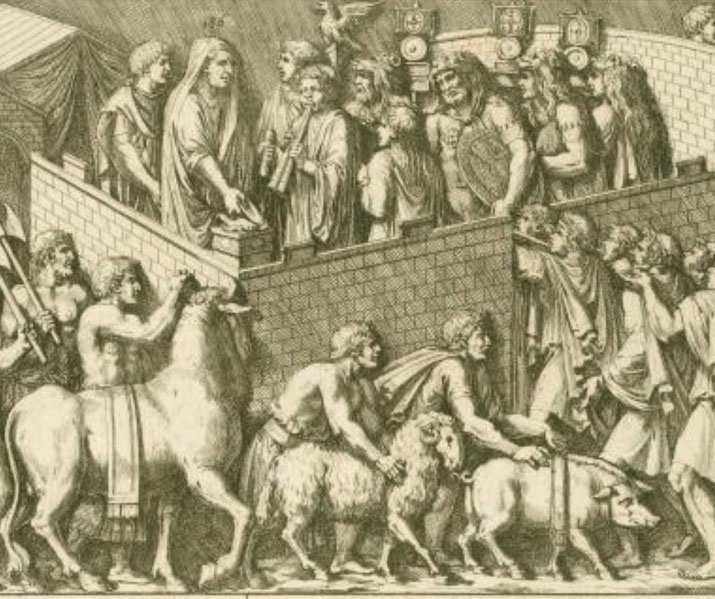

The rituals began with a public sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, situated in the Roman Forum.

This ceremony was unlike typical Roman religious practices; it was conducted in Greek style, meaning the heads of the Roman participants were not covered, and the feet of Saturn's statue were unbound, symbolizing the god's liberation.

Following the sacrifice, a public banquet was held, which was a part of the religious observance, emphasizing community and equality.

This was more than a simple feast; it was a communal ritual that brought together different strata of Roman society.

The religious significance of this banquet lay in its ability to dissolve the usual social distinctions, a practice deeply symbolic in honoring a god associated with abundance and the golden age of man.

The role of the Saturnalia King or 'King of Misrule' was another religious aspect of the festival.

Selected by lot, this figure had the authority to command others to perform entertaining tasks, a role that mimicked the traditional Roman religious practice of choosing a temporary leader during festivals.

This position, though lighthearted and comical, had its roots in the ancient tradition of the sacrificial 'scapegoat' king, a figure who would take on the sins of the community and then be expelled or executed as a part of the ritual purification process.

The religious undertones of Saturnalia also extended to its timing, coinciding with the winter solstice.

This period was significant in the Roman calendar, representing the rebirth of the year and the return of longer days.

The festival's emphasis on light, through the widespread use of candles and lamps, was a nod to the sun's triumph over darkness, a theme that resonated with the agricultural god Saturn's association with renewal and rejuvenation.

What did the Romans think of the celebrations?

Poets like Horace wrote vividly about the festival, capturing its spirit and its central role in the closing of the year.

The festival served as a safety valve, allowing for the temporary release of social tensions and the expression of a more egalitarian spirit.

This periodical relaxation of social norms helped to maintain stability in the highly stratified Roman society, a subtle yet powerful way in which the festival influenced the dynamics of Roman life.

In literature, authors such as Catullus, the celebrated Roman poet, referred to Saturnalia as the "best of days" - a testament to the joy and freedom it brought.

His writings, along with those of other literary figures like Martial and Seneca, offer insights into the customs and atmosphere of the festival, highlighting its importance in the Roman cultural milieu.

These accounts not only document the festivities but also reflect on the broader societal implications of this temporary reversal of the social order.

Artistically, Saturnalia influenced Roman mosaics, frescoes, and sculptures.

Artworks depicting scenes of revelry, feasting, and the characteristic role reversals of the festival provide a visual narrative of Saturnalia’s customs.

Such depictions served as a reminder of the joyous break from the everyday rigors of Roman life, celebrated across different classes.

Did Saturnalia become Christmas?

As the Roman Empire expanded and absorbed cultures from its conquered territories, Saturnalia too absorbed elements of other winter solstice celebrations.

This inclusivity and adaptability were key to the festival's longevity and widespread appeal.

One of the most significant transformations of Saturnalia came with the rise of Christianity within the Roman Empire.

As early Christians sought to establish their traditions, they faced the challenge of integrating or replacing deeply rooted pagan festivals.

The timing of Christmas, celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ, was strategically aligned with the winter solstice period, coinciding with Saturnalia and the Roman New Year celebrations.

By the 4th century, with the Edict of Thessalonica in 380 AD making Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire, many of the customs of Saturnalia began to be reframed within a Christian context.

As Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire, many of the customs of Saturnalia - such as feasting and gift-giving - were incorporated into the Christmas celebrations.

This amalgamation is partly attributed to the Church's strategy to adopt and Christianize popular pagan festivals to ease the transition to the new religion.

The tradition of gift-giving, feasting, and even the carnival-like atmosphere of role reversals found a new expression in Christmas and the subsequent Boxing Day traditions.

The Lord of Misrule, a figure in medieval Christmas celebrations, echoed the Saturnalia's King of Misrule, exemplifying the festival's enduring influence on European festive customs.

Moreover, the spirit of Saturnalia, emphasizing joy, freedom, and the upending of social norms, continued to resonate through the ages.

This legacy is reflected in various cultural and literary references, from Renaissance art to contemporary works, where the themes of merriment and social inversion during the winter season frequently appear.

In modern times, while the name Saturnalia may not be widely recognized, its essence survives in the customs and traditions of Christmas and New Year celebrations around the world.

The joyous atmosphere, the spirit of generosity, and even the holiday season's role as a social equalizer can be traced back to the ancient Roman festival.

In this way, Saturnalia's transformation over centuries has not diminished its legacy but rather allowed it to persist in various forms, continuing to bring warmth and celebration during the winter months.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.