Sejanus: Why the Roman emperor's most trusted friend betrayed the imperial family

Lucius Aelius Sejanus, once the most powerful man in Rome next to Emperor Tiberius, remains a historical enigma.

His rapid ascent from a trusted advisor to the very precipice of imperial power, followed by a sudden and dramatic downfall, has left historians baffled for centuries.

Who was this man who came so close to ruling the vast Roman Empire?

What were the mechanisms of his rise?

And what led to his swift fall from grace?

His early life and origins

Lucius Aelius Sejanus was born in 20 BCE in Volsinii, a city located in the Etruscan region of Italy.

His family, though not of the senatorial class, held a certain distinction in their hometown.

His father, Lucius Seius Strabo, was a man of considerable influence, serving as the prefect of the Praetorian Guard before being appointed governor of Egypt.

This early exposure to the corridors of power undoubtedly influenced young Sejanus and provided him with valuable insights into the workings of the Roman political machine.

From an early age, Sejanus displayed an aptitude for military and administrative matters.

By the time he reached adulthood, Rome was undergoing significant political shifts, with the Julio-Claudian dynasty firmly establishing its rule.

Sejanus's early career saw him serving under his father in the Praetorian Guard, a position that offered him a unique vantage point to observe the inner dynamics of the empire.

His dedication and competence did not go unnoticed, and by the time Emperor Tiberius ascended to the throne in 14 CE, Sejanus had positioned himself as a trusted figure within the imperial circle.

Sejanus' rise to power

When his father, Lucius Seius Strabo, left his role as prefect of the Praetorian Guard to govern Egypt, Sejanus was poised to fill the vacuum.

By 15 CE, he had become the sole prefect, a position that granted him significant influence over the emperor and the affairs of the state.

Emperor Tiberius, who had begun his reign with a somewhat hands-off approach to governance, increasingly relied on Sejanus for administrative and military matters.

Over the years, Tiberius came to rely heavily on Sejanus, especially in matters of governance and security.

Their bond was further solidified when Tiberius began to retreat from public life, leaving Sejanus as the primary administrator of the empire's affairs.

Sejanus's consolidation of power was a masterclass in political maneuvering, marked by strategic decisions and ruthless actions.

One of his most significant moves was the centralization of the Praetorian Guard into the Castra Praetoria in Rome around 23 CE.

This decision not only enhanced the efficiency and response time of the guard but also ensured that Sejanus had a loyal and formidable force at his immediate disposal.

With the Praetorians centralized, he could swiftly quell any dissent or uprising in the heart of the empire.

His close relationship with the imperial family

However, it wasn't just his relationship with Tiberius that defined Sejanus's interactions with the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

His ties to Livilla, Tiberius's niece and the wife of Drusus Julius Caesar, were a source of much speculation.

Rumors of a romantic relationship between the two were rife, and while the exact nature of their association remains debated, it's clear that their alliance had significant political implications.

Livilla, being closely related to the imperial line, provided Sejanus with an insider's perspective and influence within the family.

Yet, not all members of the imperial family viewed Sejanus favorably. Drusus Julius Caesar, Tiberius's son and heir apparent, reportedly had a contentious relationship with him.

Their animosity came to a head in 23 CE when a public altercation between the two took place.

By 26 CE, both Nero Caesar and Drusus Caesar, grandsons of Tiberius, were imprisoned on charges largely believed to be orchestrated by Sejanus.

Their removal from the political scene left a void that Sejanus was more than willing to fill.

Sejanus's ambitions didn't stop there. Recognizing the importance of blood ties in Roman politics, he sought to further intertwine his lineage with the Julio-Claudians.

There were suggestions that he aimed to marry Livilla after the death of Drusus, and he even betrothed his daughter to the son of Claudius, a future emperor.

Attempts to control Roman power

Sejanus recognized potential threats and acted preemptively to neutralize them.

Key figures who posed challenges to his authority, or who were seen as potential successors to Tiberius, were systematically sidelined.

Not long after Sejanus ordered his arrest, Drusus died under mysterious circumstances, with some sources suggesting that Sejanus and Livilla might have been involved in a plot to poison him.

Furthermore, Sejanus utilized the Roman legal system to his advantage. Accusations of treason became a common tool in his arsenal, allowing him to eliminate rivals and instill a sense of fear among the senatorial class.

This climate of suspicion ensured that many were hesitant to challenge his authority, lest they too become victims of such accusations.

By 31 CE, Sejanus had reached the pinnacle of his influence, with many in Rome believing he was on the cusp of officially becoming Tiberius's co-ruler or successor.

However, the very mechanisms of power and intrigue that Sejanus had so skillfully employed would soon turn against him.

Sejanus' downfall and execution

The initial signs of his waning favor with Tiberius were subtle. The emperor began to receive reports, possibly from Antonia Minor, the mother of Livilla, suggesting that Sejanus had treacherous intentions, including plots to overthrow the emperor.

These reports intimated that Sejanus and Livilla had not only conspired against Drusus but were now plotting against Tiberius himself.

The exact reasons for Tiberius's sudden change of heart remain a matter of historical debate.

Some suggest that he had grown wary of Sejanus's ambitions, while others believe that he was genuinely convinced of the treachery by the evidence presented to him.

Regardless of the motivations, Tiberius acted decisively.

On October 18, 31 CE, Sejanus was summoned to a Senate meeting, expecting to receive a new honor.

Instead, he was greeted with a letter from Tiberius, read aloud to the Senate, detailing his alleged crimes and betrayals.

Caught off guard and without the support of the Praetorian Guard, who had been strategically redirected by Tiberius's loyalists, Sejanus was arrested on the spot.

The aftermath was swift and brutal. Sejanus was imprisoned and, just a few days later, executed.

His family and close associates met a similar fate, with many facing execution or forced suicides.

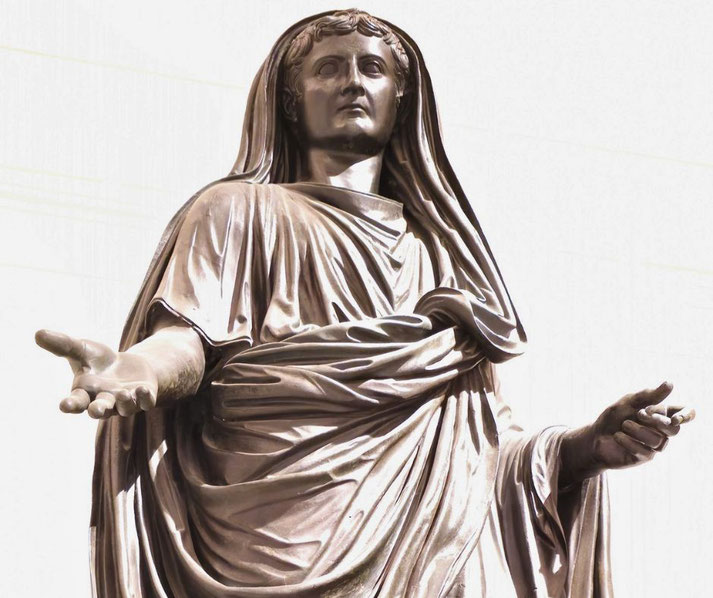

His statues were torn down, and his name was subjected to "damnatio memoriae," an ancient Roman practice where individuals were condemned and erased from official records and public memory.

Is there more to the story of Sejanus?

In the immediate aftermath of his downfall, the Roman state went to great lengths to vilify him.

His name was erased from public monuments, and his deeds were painted in the darkest hues, portraying him as a traitor who sought to undermine the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

This official stance was, in many ways, a reflection of the political climate of the time, where the narrative was controlled by those who had triumphed over him.

Ancient historians, such as Tacitus and Suetonius, offer detailed accounts of Sejanus's life, but their portrayals are often colored by the biases of their sources and the political context of their own times.

Tacitus, in his "Annals," presents Sejanus as a cunning and ambitious figure, adept at manipulating the political landscape to his advantage.

Suetonius, on the other hand, delves into the more salacious aspects of Sejanus's alleged affairs and conspiracies, painting a picture of a man consumed by ambition.

However, as time progressed and the immediacy of his actions faded, a more nuanced view of Sejanus began to emerge.

Modern historians often approach his story with a degree of caution, recognizing the potential for bias in ancient sources.

While few dispute his ambition and the ruthless methods he employed to achieve his goals, there's a growing recognition of his administrative capabilities and the stability he provided to the Roman state during a period of potential upheaval.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.