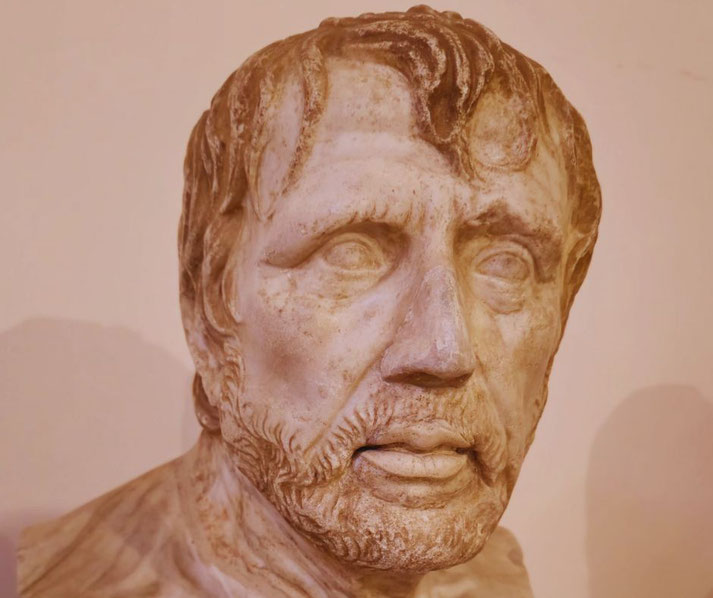

Seneca: The Roman philosopher who tried to talk sense to Emperor Nero but paid the price

Throughout Roman history, few men attempted to bring virtue and power together as seriously as Lucius Annaeus Seneca.

As a Stoic philosopher, dramatist, and political figure, he walked a narrow line between moral instruction and dangerous closeness to tyranny.

His decision to guide the young Nero placed him in a role that demanded both wisdom and political survival, yet his commitment to Stoic ideals eventually put him in conflict with the realities of imperial rule.

Seneca' early life: the making of a Stoic

Around 4 BC, or possibly slightly later, in the Roman colony of Corduba, in Hispania Baetica, Lucius Annaeus Seneca was born into a wealthy equestrian family whose status granted him access to the highest levels of Roman society.

His father was known as Seneca the Elder, and he held distinction as an accomplished rhetorician and intellectual who cultivated in his son a rigorous education that would later support a career at the heart of Roman political life.

His older brother Gallio would later serve as proconsul of Achaea, and his younger brother Mela would father the poet Lucan, which increased the family's influence in literature and public service.

He studied in Rome under leading Stoic thinkers such as Attalus and Pythagorean philosophers like Sotion, and he reportedly developed a personal commitment to reason and self-control aimed at pursuing virtue that he later expressed in both public service and philosophical treatises.

Early in his career, he gained notice for his oratorical skill under the unstable rule of Emperor Caligula, who had allegedly considered killing him out of jealousy, but had spared him because he believed that his chronic illness would soon end his life.

Then in AD 41, under Claudius, he faced banishment on charges of adultery with Julia Livilla, the emperor’s niece and sister of Caligula.

The emperor exiled him to Corsica, and there, he spent eight years in isolation, during which he composed several works, among them Consolation to Helvia, in which he defended philosophical reflection as a means to endure hardship.

That period proved restrictive and it largely solidified his reputation as a serious Stoic thinker.

How Seneca met a young Nero

Seneca returned to public life in AD 49, as Agrippina the Younger, who had married Emperor Claudius, apparently arranged for his recall from exile and appointed him tutor to her son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus.

This boy, born in AD 37, carried a prestigious lineage through Agrippina’s descent from Augustus.

After Claudius adopted him in AD 50 and renamed him Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus, Seneca quickly gained a vital role in forming the future emperor’s mind and character.

At that stage, Agrippina sought to elevate her son as heir, and Seneca offered both intellectual prestige and political tact.

To gain public approval, she promoted Seneca's image as a man of virtue and eloquence, capable of which helped justify her son's claim.

Together with the newly appointed praetorian prefect, Sextus Afranius Burrus, Seneca helped direct Nero’s education and personal conduct.

As tutor, he exposed the boy to Greek and Roman literature, taught rhetorical structure, and tried to teach Stoic principles that combined self-control with duty and clear moral judgement.

His lessons focused on the idea that power without virtue brought ruin. Seneca primarily advocated restraint as a means to produce a ruler who could restrain desire and reject cruelty.

Initially, that aim seemed within reach. Nero responded well to the influence of both Seneca and Burrus during the earliest years of his rule.

What did Seneca teach Nero?

After Claudius died in AD 54, Nero ascended the throne at the age of sixteen.

During the first five years of his reign, often remembered as the quinquennium Neronis, Seneca and Burrus acted as stabilising forces within the imperial administration.

At that time, they promoted mercy in legal matters, checked military excess, and encouraged Nero to present himself as a restorer of republican virtue.

Seneca crafted speeches that praised harmony with the Senate and respect for Roman tradition.

One important work, De Clementia, which he addressed to Nero early in his reign around AD 55, defined an ideal ruler as one who controlled anger and dispensed mercy as an act of strength, not weakness.

That treatise urged Nero to use power with calm restraint. Seneca warned that tyrants inspired fear without winning loyalty, and that revenge harmed both ruler and people.

His arguments showed Stoic principles: rational thought and emotional discipline that underpinned moral responsibility.

Later, in De Ira and De Vita Beata, he returned to similar ideas. He advised Nero to control passion, avoid flattery, and live modestly despite the luxuries of court.

In De Vita Beata, he also clarified that true happiness came from virtue, not pleasure or excess.

Still, Seneca lived with great wealth. Critics such as Tacitus and Dio Cassius later argued that his wealth and lifestyle did not match Stoic humility.

Even so, many of his teachings rested on the view that virtue must be pursued in any circumstances, even when surrounded by corruption.

Why Nero began to turn on Seneca

By AD 59, Nero began to disregard his early advisors. He had Agrippina killed that year, and that act, brutal and politically risky, demonstrated Nero’s desire to rule without limits or interference.

After Burrus had died in AD 62, Seneca’s influence declined rapidly, and so he requested permission to retire and even offered to return his wealth, yet Nero refused.

According to Tacitus, he grew increasingly suspicious of his former teacher’s independence and wealth.

At court, rivals such as Tigellinus had replaced Burrus as praetorian prefect, and they spread rumours that Seneca remained driven by personal aims, insincere, and secretly aligned with other elites.

Eventually, Nero treated him as a threat. He surrounded himself with advisors who encouraged cruelty and extravagant self-promotion, and, as a result, Seneca was now sidelined.

The philosopher wrote less frequently and tried to withdraw from public life.

Soon, events moved against him. In AD 65, a plot to assassinate Nero and replace him with Gaius Calpurnius Piso led to a broad round-up of suspected conspirators.

Several of the accused had alleged ties to Seneca, though clear evidence that linked him to the conspiracy never emerged.

Still, Nero ordered his death. That choice removed a moral critic and effectively warned others that virtue would not shield them from punishment.

How Seneca's death defied Nero

When imperial guards arrived at his villa, Seneca received them without panic, and so he called for friends and calmly prepared for death.

According to Tacitus in Annals 15.62–64, he opened his veins but bled too slowly.

Then he drank poison, which also failed. At last, he entered a hot bath and he hoped that the heat would draw out his remaining strength.

He died calmly, surrounded by students who had once looked to him for guidance.

His final moments clearly showed the Stoic teachings that he had delivered across his life.

Death, he argued, should never be feared. Instead, it should be accepted as part of nature.

By facing his death without appeal or complaint, Seneca denied Nero the satisfaction of watching him suffer.

He also demonstrated that even under tyranny, a philosopher could meet death with dignity.

Importantly, Roman elites viewed such suicides as a respected way to avoid disgrace.

For Seneca, it allowed him to make a final statement of moral courage. His decision to die on his own terms gave him one last form of control within a world that had turned against him.

His wife Pompeia Paulina attempted to die alongside him, but Nero ordered her to live.

Why Seneca's life and philosophy still matter today

Seneca’s writings remarkably survived for two thousand years. His Letters to Lucilius, On the Shortness of Life, and On Tranquillity of Mind continue to offer guidance on how to live well under pressure, how to face hardship, and how to remain morally anchored in difficult times.

Thinkers during the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and the modern era (among them Michel de Montaigne, Francis Bacon, Voltaire, and Emerson) turned to his words when grappling with corruption, injustice, or loss.

Admittedly, Seneca’s considerable fortune and position under Nero left some readers unsettled.

He urged simplicity but owned grand villas. He preached restraint but held power at court.

Even so, his works reveal self-awareness and occasional remorse. He never claimed perfection, and he instead advised constant effort toward virtue, even when circumstances made virtue difficult to uphold.

Early Christian writers even admired his moral tone. Later traditions claimed he corresponded with St Paul, but historians consider these letters to be later forgeries.

Today, many readers return to Seneca because he spoke plainly about timeless questions.

How should one act in a corrupt system? How should one respond to hatred or loss? How can one lead without cruelty?

His life did not offer perfect answers. Still, it showed that philosophy offered a path to endure hardship and preserve dignity.

Interestingly, Nero only outlived Seneca by only three years. After his death in AD 68, the Senate condemned him and likely subjected his memory to a form of damnatio memoriae, though historians debated how extensive this was.

Seneca, by contrast, became one of Rome’s most studied philosophers. His efforts to guide Nero failed.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.