The history of ancient Israel from Abraham to Roman rule

The history of ancient Israel is a captivating journey that spans centuries, weaving together tales of faith, leadership, conflict, and resilience.

From its early beginnings with the patriarchs to its complex relationships with neighboring empires, Israel's past offers a unique window into the evolution of a people and their enduring beliefs.

The land, often referred to as the crossroads of civilizations, bore witness to monumental events that shaped not only the destiny of the Israelites but also influenced the broader course of world history.

Origins and early settlement

The origins of ancient Israel trace back to the early second millennium BCE, with the journey of Abraham, a Semitic patriarch, from Ur in Mesopotamia to the land of Canaan.

This migration, driven by divine promise, laid the foundation for the establishment of a new lineage.

Abraham's descendants, particularly Isaac and Jacob, further solidified their ties to Canaan, with Jacob later being named Israel, giving rise to the term 'Israelites' for his descendants.

The narrative takes a significant turn around the 13th century BCE, when the Israelites found themselves in Egypt.

Initially welcomed due to the actions of Joseph, one of Jacob's sons, they later faced oppression and were subjected to slavery.

This period of bondage culminated in one of the most pivotal events in Israelite history: the Exodus.

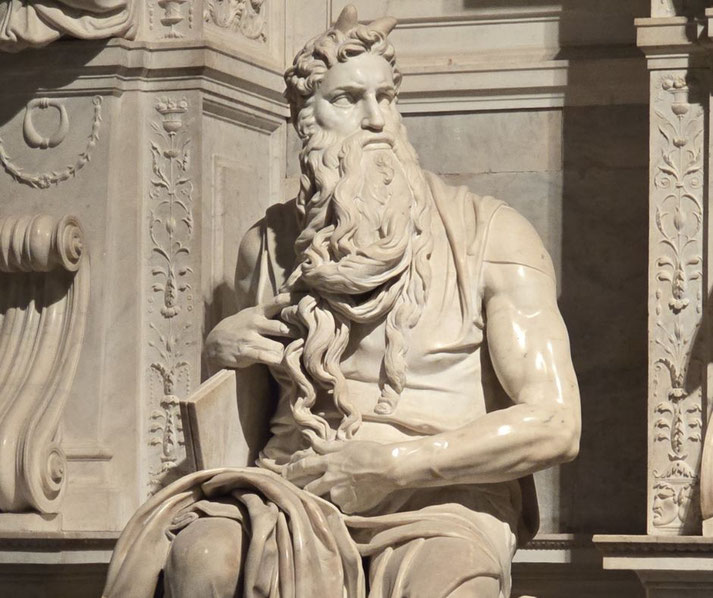

Led by Moses, the Israelites embarked on a decades-long journey through the desert, during which they received the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai, a foundational moment for their emerging religious identity.

Upon their return to Canaan, around the late 13th to early 12th century BCE, the Israelites faced the challenge of settling into a land inhabited by various city-states and tribal groups.

Under the leadership of Joshua, they embarked on a series of military campaigns to establish their presence.

Over time, through a combination of warfare, alliances, and settlements, the Israelites carved out territories for the twelve tribes, laying the groundwork for the nation's future political and cultural development.

Period of the 'judges'

Following the conquest and settlement of Canaan, the Israelites entered a distinct phase in their history, commonly referred to as the Period of the Judges, which spanned from around the 12th to the early 10th century BCE.

During this era, Israel did not have a centralized monarchy. Instead, leadership was often provided by charismatic individuals known as judges.

These leaders were not judges in the modern sense of legal adjudicators but rather chieftains or military leaders who rose to prominence in times of crisis, rallying tribes to defend against external threats.

One of the earliest and most notable judges was Deborah, a prophetess who, alongside the military leader Barak, led the Israelites to victory against the Canaanite king Jabin and his general Sisera.

This triumph is celebrated in the Song of Deborah, one of the oldest pieces of Hebrew literature.

Another significant figure from this period was Gideon, who successfully defended Israel against the Midianites using unconventional warfare tactics.

Then there was Samson, whose legendary strength and tumultuous relationship with the Philistines have been immortalized in numerous tales and adaptations.

However, the Period of the Judges was not just about individual exploits. It was a time of tribal fragmentation and infighting, with the Israelites often lapsing into idolatry and straying from their covenant with God.

This cyclical pattern of apostasy, oppression by neighboring groups, repentance, and deliverance by a judge became a recurring theme.

The Philistines, in particular, emerged as a formidable adversary during this era, leading to frequent clashes.

The united monarchy under Saul, David, and Solomon

The transition from the Period of the Judges to a centralized monarchy marked a pivotal shift in the political landscape of ancient Israel.

This era, known as the United Monarchy, spanned the 10th century BCE and saw the rise of Israel's first kings: Saul, David, and Solomon.

Saul, from the tribe of Benjamin, emerged as Israel's inaugural king around the late-11th century BCE.

His ascension was initially met with widespread approval, as he successfully rallied the tribes against their common adversaries, particularly the Philistines.

However, Saul's reign was marred by personal struggles and conflicts, especially with the young David, a shepherd from Bethlehem who gained fame by defeating the Philistine giant, Goliath.

As tensions escalated, a tragic sequence of events led to Saul's downfall and eventual death on the battlefield.

David, having garnered significant support during Saul's reign, assumed the throne and embarked on a series of military campaigns that expanded Israel's borders and influence.

His most notable achievement was the capture of Jerusalem around 1000 BCE, which he established as the political and religious capital of the united kingdom.

Under David's leadership, Israel enjoyed relative peace and prosperity, setting the foundation for a golden age.

Solomon, David's son, succeeded him and is best remembered for his wisdom and monumental building projects.

The most iconic of these was the construction of the First Temple in Jerusalem, which became the central place of worship for the Israelites and housed the Ark of the Covenant.

Solomon also forged alliances through marriage and diplomacy, enhancing Israel's regional stature.

However, his later years were fraught with challenges. Extravagant spending on building projects and the introduction of foreign cults, due to his many foreign wives, led to internal discontent.

By the end of Solomon's reign, the seeds of division were sown. The heavy taxation and forced labor policies had alienated significant portions of the population.

Civil war and the division of the kingdom

Following Solomon's death around 930 BCE, the unity that once characterized the Israelite kingdom began to unravel.

Rehoboam, Solomon's son, ascended to the throne, but his early decisions, particularly his refusal to alleviate the burdensome taxes and forced labor, ignited widespread discontent.

This dissatisfaction culminated in a significant revolt led by Jeroboam, an official from the northern tribes.

The outcome was a profound split, with the northern ten tribes establishing the Kingdom of Israel, and the southern tribes, primarily Judah and Benjamin, forming the Kingdom of Judah with Jerusalem as its capital.

The Kingdom of Israel, with its capital initially in Shechem and later in Samaria, saw a succession of dynasties and rulers.

Jeroboam, its first king, set up alternative religious centers in Bethel and Dan, partly to counteract the allure of the Temple in Jerusalem.

Over the years, Israel grappled with internal power struggles and external threats, especially from the expanding Assyrian Empire.

Prophets like Elijah and Elisha played significant roles during this period, challenging the Israelite kings and advocating a return to the worship of Yahweh.

Conversely, the Kingdom of Judah, though smaller, benefited from the religious and administrative structures established during the United Monarchy.

The Davidic line continued to rule, with some kings, like Hezekiah and Josiah, noted for their religious reforms and efforts to centralize worship in the Jerusalem Temple.

However, Judah too faced its share of challenges, from internal religious apostasy to external pressures, particularly from the Assyrians and later the Babylonians.

The fate of the two kingdoms diverged dramatically in the late 8th century BCE.

The Kingdom of Israel, after years of political instability and Assyrian pressure, fell to the Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III and later Shalmaneser V.

The culmination of these campaigns was the siege of Samaria by Sargon II around 722 BCE, leading to the exile of a significant portion of the Israelite population and the end of the northern kingdom.

The Kingdom of Judah, though it managed to survive the Assyrian onslaught, eventually faced the rising power of Babylon.

Despite periods of allegiance, tensions reached a breaking point in the early 6th century BCE.

Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon laid siege to Jerusalem, resulting in the city's fall in 586 BCE, the destruction of the Temple, and the beginning of the Babylonian Exile for the Judeans.

Foreign dominance and exile in Babylon

The fall of Jerusalem in 586 BCE to Nebuchadnezzar II marked a profound shift in the history of the Israelites.

With the city's destruction and the subsequent exile of a significant portion of the Judean population to Babylon, the very fabric of their communal and religious life was disrupted.

This Babylonian Exile, also known as the Captivity, was a period of reflection, adaptation, and transformation for the Israelites.

In Babylon, far from their homeland and the ruins of their once-glorious Temple, the exiles faced the challenge of preserving their identity and faith.

Without the centralizing force of the Temple, synagogues began to emerge as places of worship, study, and community gathering.

The role of scribes and scholars became increasingly important, leading to the compilation and editing of various biblical texts.

This period also saw the rise of prominent figures like the prophet Ezekiel, who provided spiritual guidance and hope to the exiled community, emphasizing personal responsibility and envisioning a future return to their homeland.

While the Israelites grappled with their new reality in Babylon, geopolitical shifts were occurring in the broader Near East.

In 539 BCE, a significant event reshaped the region's dynamics: the rise of the Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great.

The Persians, having conquered the Babylonians, adopted a more benevolent approach to governance.

Cyrus issued a decree allowing various exiled communities, including the Israelites, to return to their homelands and restore their places of worship.

This edict marked the beginning of the end of the Babylonian Exile.

The return to Judah, which occurred in waves over several decades, was not without challenges.

The land they returned to was in ruins, and the task of rebuilding, both physically and spiritually, was daunting.

Under leaders like Zerubbabel, Joshua the High Priest, and later Ezra and Nehemiah, the Israelites embarked on projects to rebuild the Temple and the walls of Jerusalem.

These efforts, coupled with religious reforms, aimed to reestablish and fortify their distinct identity in a landscape still dominated by foreign powers.

Conquest by Alexander the Great and the Romans

The subsequent centuries saw Judah, now commonly referred to as Judea, under the influence or direct control of various empires.

The Persians were succeeded by the Greeks following Alexander the Great's conquests in the late 4th century BCE.

After his death, his empire fragmented, and Judea found itself caught between the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt and the Seleucid dynasty in Syria.

By the 2nd century BCE, under the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, tensions reached a boiling point.

His policies, which included Hellenization efforts and the desecration of the Temple, sparked a revolt led by the Maccabean family.

This successful rebellion resulted in the rededication of the Temple, an event commemorated by the Jewish festival of Hanukkah, and the establishment of the Hasmonean dynasty.

The Hasmoneans, initially priestly leaders, eventually adopted the title of king and expanded the borders of Judea.

However, internal conflicts and the rising power of Rome in the Mediterranean world weakened their hold.

By the mid-1st century BCE, Rome had established its dominance over Judea, first through client kings like Herod the Great, known for his extensive building projects including the renovation of the Second Temple, and later through direct Roman governors.

Throughout the Second Temple Period, Judea experienced significant cultural and religious developments.

The influence of Hellenism led to debates about assimilation and identity. Sectarian groups, such as the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, and Zealots, emerged, each with distinct interpretations of Judaism and visions for the future.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in the 20th century provided valuable insights into the religious diversity and thought of this period.

Roman rule and the end of ancient Israel

Following Herod's death, his kingdom was divided among his sons, but Roman intervention became more direct as the years progressed.

By 6 CE, Judea was incorporated as a province of the Roman Empire, governed by Roman procurators.

This shift in governance brought with it increased taxation and Roman legal practices, often at odds with Jewish customs and laws.

The cultural and religious differences between the Roman rulers and the Jewish populace, combined with economic strains and perceived religious affronts, led to growing tensions.

These sentiments were further exacerbated by various Jewish groups, including the Zealots, who vehemently opposed Roman rule and advocated for rebellion.

The situation reached a breaking point in 66 CE when widespread revolts erupted against Roman authority, initiating the First Jewish-Roman War.

Over the next four years, the Romans, under generals Vespasian and his son Titus, waged a brutal campaign to suppress the rebellion.

The climax came in 70 CE when Roman legions besieged Jerusalem. The city eventually fell, and the Second Temple, the religious heart of Jewish life, was destroyed.

This catastrophic event had profound implications for Jewish identity and practice, signaling the end of the centralized cultic worship associated with the Temple.

However, the Jewish resistance did not end with the fall of Jerusalem. Over the next six decades, two more revolts would challenge Roman authority.

The most significant was the Bar Kokhba Revolt from 132 to 136 CE, led by Simon Bar Kokhba, who was viewed by many as the Messiah.

Despite initial successes, the revolt was brutally suppressed by the Roman Emperor Hadrian.

In its aftermath, Hadrian took measures to further Romanize Jerusalem, renaming it Aelia Capitolina and constructing a temple to Jupiter on the ruins of the Jewish Temple.

The cumulative effects of these revolts and Roman reprisals led to significant demographic and cultural shifts.

Many Jews were killed, enslaved, or dispersed throughout the Roman Empire.

The center of Jewish life and scholarship gradually moved away from Judea, laying the groundwork for the Jewish diaspora that would spread across the Mediterranean and beyond.

In the wake of these tumultuous events, the contours of Jewish identity and practice began to change.

The Pharisaic tradition, emphasizing study and interpretation of the Torah, evolved into Rabbinic Judaism.

This new form of Judaism, with its emphasis on the oral tradition and communal study, would play a pivotal role in preserving Jewish identity and beliefs in the centuries to come.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.