Why was Abraham Lincoln assassinated?

On a seemingly ordinary evening in April 1865, as the Civil War's echoes were fading, President Abraham Lincoln settled into his box at Ford's Theatre, unaware that it would be his final act in life's drama.

The gunshot that rang out from John Wilkes Booth's pistol did not just silence a president; it sent shockwaves through a nation struggling to heal.

This single event plunged the United States into a deeper abyss of grief and uncertainty, raising questions that still resonate with us today.

The remarkable life of Abraham Lincoln

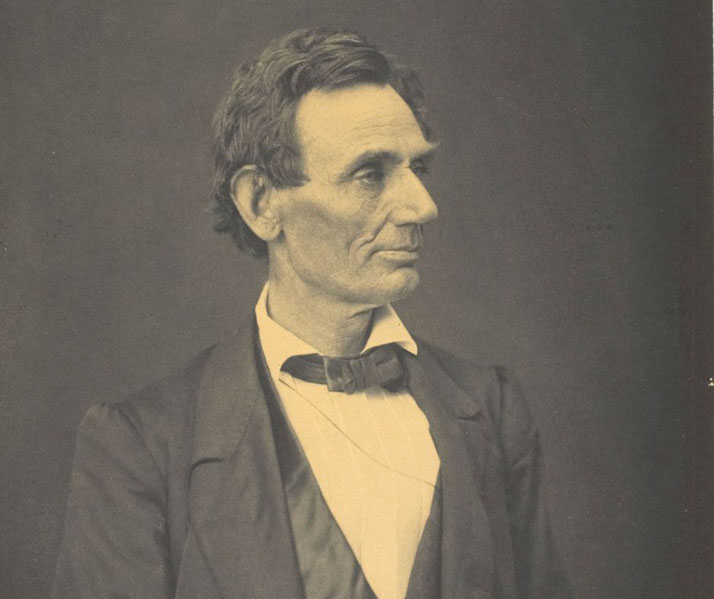

Abraham Lincoln, born on February 12, 1809, in a humble log cabin in Kentucky, rose from modest beginnings to become one of the most influential Presidents of the United States.

His early life, spent in Indiana and later Illinois, was marked by hard work and a voracious appetite for learning, despite limited formal education.

Lincoln's journey into politics began in the 1830s; he served in the Illinois State Legislature and later in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1846.

However, it was his election as the 16th President of the United States in 1860 that thrust him onto the center stage of national politics at a time of profound crisis.

Lincoln's presidency was dominated by the American Civil War, which began just a month after he took office.

His unwavering commitment to preserving the Union and his Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, which declared freedom for all slaves in Confederate-held territory, are hallmarks of his tenure.

Lincoln faced considerable opposition and immense challenges throughout his presidency, including managing a divided nation and navigating the complexities of wartime politics and leadership.

Despite these challenges, he was re-elected in 1864, a testament to his enduring vision for a united and free nation.

Lincoln's ability to articulate his vision for America, notably in the Gettysburg Address delivered on November 19, 1863, showcased his skill as an orator and his profound understanding of the principles of democracy and human equality.

His speeches and writings during this period reflect a deep philosophical and moral grounding, particularly regarding the issues of slavery and human rights.

The bloodshed of the Civil War

The Civil War, a defining conflict in American history, began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in South Carolina, just a month after Abraham Lincoln's inauguration as President.

This war stemmed from deep-rooted tensions between the Northern and Southern states, primarily over issues of slavery and states' rights.

The industrial North, advocating for a unified nation and increasingly opposing slavery, clashed with the agrarian South, which sought to preserve its way of life, including the institution of slavery.

As the war progressed, battles such as the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 and the Siege of Vicksburg, culminating on July 4, 1863, marked turning points.

The Confederacy, under leaders like General Robert E. Lee, initially saw several victories, fostering a belief in a possible Southern triumph.

However, the Union's industrial strength, along with strategic leadership under generals like Ulysses S. Grant, began to tip the scales in favor of the North.

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, effective January 1, 1863, transformed the war's nature.

While initially focused on preserving the Union, the war now also took on the mantle of a crusade against slavery.

This move not only redefined the war's moral and political stakes but also allowed for the enlistment of African American soldiers, further bolstering the Union's manpower.

The war's impact extended beyond the battlefield. It affected the lives of millions of Americans, both in the Confederacy and the Union.

The economies of both the North and South were significantly strained, with the South experiencing widespread devastation and economic collapse.

The social fabric of the nation was also profoundly altered, particularly with the liberation of millions of slaves.

As the war drew to a close in April 1865, with Confederate forces increasingly depleted and Union victories more decisive, the Confederacy's collapse seemed imminent.

General Lee's surrender to General Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, effectively marked the end of the Civil War.

John Wilkes Booth and the plot against Lincoln

John Wilkes Booth, born on May 10, 1838, in Maryland, emerged as one of the most notorious figures in American history following his assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

Booth, a well-known actor and fervent supporter of the Confederate cause, harbored deep resentment towards Lincoln and the Union.

He viewed Lincoln's presidency and actions, especially the Emancipation Proclamation, as tyrannical and destructive to the Southern way of life.

Initially, Booth plotted not to kill Lincoln but to abduct him. This plan, devised in late 1864 and early 1865, involved kidnapping the President and taking him to Richmond, the Confederate capital, in a bid to demoralize the Union and negotiate better terms for the South.

Booth recruited several co-conspirators for this plot, including Lewis Powell, David Herold, George Atzerodt, and Mary Surratt, the owner of a boarding house where the conspirators frequently met.

However, as the Confederacy's defeat became increasingly apparent, Booth's plans shifted dramatically towards assassination.

The opportunity presented itself when Booth learned of Lincoln's plan to attend a performance at Ford's Theatre on April 14, 1865.

Booth, familiar with the theatre's layout and having easy access due to his status as a well-known actor, saw this as the perfect chance to carry out his new objective.

On the night of the assassination, Booth's co-conspirators were also assigned their roles in the broader scheme.

Lewis Powell was tasked with killing Secretary of State William H. Seward, David Herold was to assist Powell, and George Atzerodt was assigned to assassinate Vice President Andrew Johnson.

How Lincoln was killed

Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. was a three-story building located on 10th Street.

President Abraham Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, were set to attend the performance of "Our American Cousin."

The Lincolns, accompanied by Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris, arrived late but were greeted with enthusiastic applause as they settled into the presidential box, a lavish and conspicuous location overlooking the stage.

Around 10:15 PM, as the audience's attention was absorbed by the play, Booth stealthily entered the presidential box.

With a derringer pistol in hand, he shot Lincoln in the back of the head at point-blank range.

The bullet entered near the left ear, lodging behind the right eye.

The sound of the gunshot was initially not recognized by many in the audience, attributed perhaps to a part of the play.

However, the reality of the situation became terrifyingly clear as Major Rathbone, who attempted to stop Booth, was severely wounded by Booth's knife.

Booth then leaped onto the stage, shouting "Sic semper tyrannis!" Despite breaking his leg in the fall, he managed to escape, leaving behind a scene of chaos and confusion.

Lincoln was carried across the street to the Petersen House, where he was laid in a small back bedroom.

Doctors and attendants worked frantically to assist him, but the wound was fatal. Lincoln would never regain consciousness.

Surrounded by members of his cabinet and other officials, he remained in a coma for nine hours until his death at 7:22 AM on April 15, 1865.

The hunt for the killers

Following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865, a massive manhunt ensued for John Wilkes Booth and his co-conspirators.

This pursuit became one of the most extensive and intense operations of its kind in American history.

The search was led by the War Department, with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton coordinating efforts to capture those responsible for the President's death.

Booth, having injured his leg during his escape from Ford's Theatre, fled on horseback to Southern Maryland, accompanied by David Herold.

The pair initially sought refuge at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, who set Booth's broken leg on April 15.

Over the next several days, Booth and Herold evaded capture, moving through rural Maryland and into Virginia.

Meanwhile, other conspirators were rapidly being apprehended. Lewis Powell, who had attacked Secretary of State William H. Seward on the same night as the assassination, was captured on April 17.

George Atzerodt, assigned to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson but who had failed to carry out the act, was arrested on April 20.

Mary Surratt, owner of the boarding house where the conspirators had met, was also taken into custody.

The manhunt for Booth intensified as thousands of soldiers and law enforcement officers scoured the countryside.

The search came to a climax on April 26, when Booth and Herold were discovered hiding in a tobacco barn on the farm of Richard Garrett in Virginia.

Herold surrendered, but Booth refused, declaring he would rather fight to the death.

The barn was set on fire to flush Booth out, and he was subsequently shot by Sergeant Boston Corbett.

Booth died from his injuries a few hours later.

Following the death of Booth, the focus shifted to the trial of the captured conspirators.

In a military tribunal that commenced in May 1865, eight people were tried for their involvement in the conspiracy.

Four of them, including Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt, were sentenced to death by hanging, which was carried out on July 7, 1865.

The others received prison sentences of varying lengths.

How America mourned for Lincoln

As news of the assassination spread, a profound sense of shock and grief enveloped both the North and the South.

Public buildings, businesses, and homes were draped in black bunting as a symbol of mourning.

On April 19, the day of Lincoln's funeral in Washington, D.C., businesses closed, and thousands lined the streets to pay their respects as the funeral procession passed.

Lincoln's body was then placed on a train for a 1,654-mile journey back to his home in Springfield, Illinois.

This journey, which began on April 21 and concluded on May 3, 1865, became an extraordinary event in itself.

The funeral train passed through 180 cities and seven states, allowing millions of Americans to participate in a shared national mourning.

In each city, Lincoln's body was taken to a public area where citizens could pay their respects.

The scenes were ones of profound grief and solemnity; people of all ages and from all walks of life came to bid farewell to a leader they revered.

The impact of Lincoln's assassination extended beyond the immediate expressions of grief.

His death came at a critical juncture, just as the Civil War was ending and the difficult process of Reconstruction was beginning.

Lincoln, who had envisioned a lenient Reconstruction policy, aimed at healing the nation's wounds, was succeeded by Vice President Andrew Johnson, whose approach to Reconstruction and relationship with Congress differed significantly from Lincoln's.

This change in leadership had lasting implications for the post-war era, particularly in the South, where Reconstruction policies were implemented.

Lincoln's assassination also left a lasting mark on the national memory. He was enshrined as a martyr for the Union and the cause of freedom, and his legacy continued to shape American history.

Monuments and memorials were erected in his honor, and his life and death became central themes in the nation's collective memory of the Civil War.

In the years following, the mourning for Lincoln evolved into a deeper reflection on his contributions to the nation.

His commitment to preserving the Union and his stance against slavery were celebrated and became integral to the American narrative of progress and justice.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.