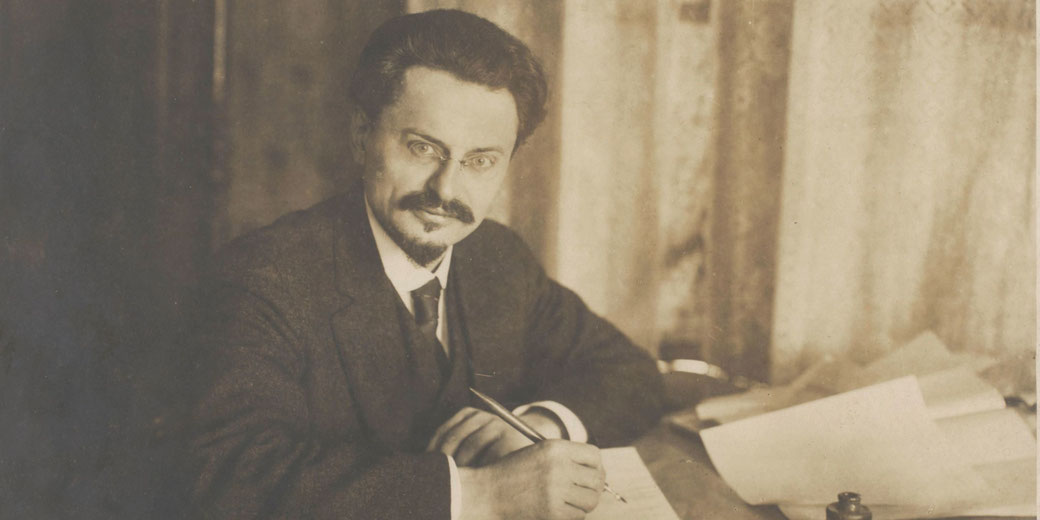

Revolution betrayed: The tragic death of Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky was a towering figure in the early 20th-century political landscape. He was as a key Marxist theorist, military leader, and architect of the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War.

In particular, his ideas, including the theory of Permanent Revolution, challenged the prevailing orthodoxy of the time.

However, it set him on a collision course with other Soviet leaders, most notably Joseph Stalin.

How Trotsky became a key leader in the revolution

Born Lev Davidovich Bronstein on November 7, 1879, in Yanovka, Ukraine, Leon Trotsky grew up on his family's farm.

Though his upbringing was relatively comfortable, the stark inequalities and social injustices of Tsarist Russia were not lost on the young Trotsky.

His intellectual curiosity and growing political awareness led him to the vibrant revolutionary circles of Odessa, where he first encountered Marxist ideas.

It was here that he adopted the pseudonym "Trotsky," and he quickly became a prominent figure in the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).

It was his eloquence and unwavering commitment to revolutionary principles that particularly set him apart from his contemporaries.

However, his activities led to his arrest on multiple occasions and was ultimately exiled as a dangerous political prisoner.

In the year 1917, he returned from exile after the February Revolution. He then joined the Bolshevik faction of the RSDLP and became a close ally of Vladimir Lenin.

Surprisingly, his role in the later October Revolution was pivotal; as the chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, he masterfully orchestrated the insurrection that brought the Bolsheviks to power.

Following the revolution, Trotsky's influence continued to grow as he took on the role of People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs and later the leader of the Red Army.

In fact, his military strategies were instrumental in the Bolshevik victory during the Russian Civil War.

Fall from power and exile from Russia

After the death of Vladimir Lenin in 1924, there was a power struggle within the Soviet leadership.

Trotsky's unwavering commitment to international revolution and his vocal criticism of the growing bureaucracy within the Communist Party put him at odds with Joseph Stalin.

As Stalin consolidated his power, Trotsky's influence began to wane, and his ideological stance became a liability.

Then, the rift between Trotsky and Stalin deepened, turning into a bitter and public feud.

Trotsky's calls for greater democracy within the Party and his criticism of Stalin's policies were met with increasing hostility.

By 1927, he was expelled from the Central Committee, and his followers, known as the Left Opposition, were systematically marginalized.

In 1928, Trotsky was exiled to Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan, a remote and isolated location.

But even in exile, he continued to write and agitate, refusing to be silenced. However, his continued activism only further enraged Stalin.

Finally, Trotsky was expelled from the Soviet Union entirely in 1929.

He sought refuge in Turkey, France, Norway, but finally settled in Mexico. However, Trotsky's life constantly surveillance, and he even received regular threats and attempts on his life by Soviet agents.

Nevertheless, he remained intellectually active, writing some of his most significant works and founding the Fourth International.

As a result, his home in Mexico City became a hub for dissident communists and intellectuals from around the world.

Why did Stalin and Trotsky disagree?

At the heart of the ideological battle between Trotskyism and Stalinism were two fundamentally different visions of how to achieve a socialist society.

Trotsky's theory of Permanent Revolution held that the socialist revolution should not be confined to one country but must spread internationally.

He believed that the working class in advanced capitalist countries would rise in solidarity with the proletariat in less developed nations.

This internationalist perspective was rooted in Trotsky's belief in the interconnectedness of the world's working class and the necessity of a worldwide socialist transformation.

Stalin, on the other hand, advocated for "Socialism in One Country." He argued that the Soviet Union should focus on building socialism within its borders and strengthening its position on the world stage.

This approach was more pragmatic and nationalistic, emphasizing the need to protect and consolidate the gains of the revolution in the face of external threats.

In practice, Stalin's policies were defined by a centralization of power, suppression of dissent, and a willingness to make compromises with capitalist nations to ensure the Soviet Union's survival.

Consequently, Trotsky's insistence on international revolution led him to criticize the Soviet Union's alliances with capitalist countries.

In contrast, Stalin's approach led to a more authoritarian regime. It exercised purges, show trials, and the suppression of opposition, including the persecution of Trotsky and his followers.

The battle between Trotskyism and Stalinism also played within the international communist movement.

Specifically, Trotsky's formation of the Fourth International in 1938 was a direct challenge to Stalin's control over the Comintern, the international communist organization.

This schism reflected deeper divisions within the global left, with different factions aligning themselves with either Trotsky's internationalism or Stalin's focus on national interests.

How Trotsky was assassinated

Trotsky knew that he was a marked man. The Soviet secret police, the NKVD, had already made attempts on his life.

Yet, Trotsky continued to write, speak, and engage with the international communist movement.

Then, Ramón Mercader, a Spanish communist recruited by the NKVD and posing as a sympathetic Belgian journalist named Jacques Mornard, Mercader managed to gain Trotsky's trust over several months.

Mercader's infiltration into Trotsky's inner circle was a slow and deliberate process.

On August 20, 1940, Mercader was invited into Trotsky's study under the pretense of discussing an article.

As Trotsky leaned over his desk to read the manuscript, Mercader struck him with an ice axe.

The attack was brutal and unexpected, and Trotsky's guards were initially unaware of what had happened.

Despite his grave injury, Trotsky managed to fight back, and his guards soon apprehended Mercader.

Trotsky was rushed to the hospital, where he died a day later. The news of his death reverberated around the world.

The assassination was a deeply personal betrayal, carried out by a man who had been welcomed into Trotsky's home.

When Ramón Mercader was put on trial, it revealed the extent of the Soviet involvement in the assassination.

Despite attempts to conceal his true identity and the motivations behind the attack, the connections to the NKVD were eventually uncovered.

Ultimately, Mercader was sentenced to 20 years in prison. However, he remained unrepentant, and viewed himself as a soldier in the service of the revolution.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.