The terror of the gulags: Stalin’s iron-fisted control over Soviet society

In the depths of Siberia, where the biting cold could freeze the soul, a chilling aspect of human history unfolded. From the 1920s through to the 1950s, under the iron-clad rule of Joseph Stalin, a system of labor camps known as 'gulags' carved a harsh scar on the psyche of the Soviet Union.

These camps, largely obscured from public scrutiny and misunderstood by the outside world, housed political prisoners, criminals, and millions of ordinary people whose only crime was falling afoul of Stalin's regime.

But what were these gulags really like and why were they originally built?

How did they function, and how did their existence influence the course of Soviet and world history?

The history of gulags before Stalin

The origins of the gulag system lie not with Joseph Stalin, but in the tumultuous years following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

The new Soviet government, led by Vladimir Lenin, grappled with consolidating their rule, and constructing a new society out of the ashes of the Russian Empire.

In addition, they were struggling to manage the Civil War against the White forces.

It was during this time, in 1919, that the first concentration camps began to emerge in Russia.

The term "gulag" is an acronym for "Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei," or "Main Camp Administration," the government agency responsible for Soviet forced labor camp systems.

It wasn't formally established until 1930, but in the years after the revolution, Lenin's government set up a number of forced labor camps for a variety of purposes, including managing political dissent and economic hardship.

For instance, the Solovki prison camp, initially a monastery, became a prototype for the later gulag system.

During the 1920s, these camps expanded under Lenin's New Economic Policy (NEP), an attempt to reinvigorate the Soviet economy by incorporating aspects of capitalism.

The camps served as a place to send those convicted of crimes. However, they were also seen as a method of 'reeducating' counter-revolutionaries and reintegrating them into the socialist system.

Stalin's rise to power and growing paranoia

Joseph Stalin rose to power following the death of Vladimir Lenin in 1924.

Although, it wasn't until the late 1920s that he had consolidated enough power to take full control of the Soviet Union.

As the new General Secretary of the Communist Party, Stalin began to enact sweeping changes in Soviet society and economy.

Stalin's vision for the Soviet Union was one of rapid industrialization and collectivization.

He believed that the Soviet Union needed to modernize quickly to survive in a hostile world surrounded by capitalist powers.

His first Five-Year Plan, which was launched in 1928, aimed at transforming the largely agrarian society into an industrial powerhouse.

This process was extremely disruptive. It led to widespread upheaval, resistance, and famine, particularly during the collectivization of agriculture.

Simultaneously, Stalin began to consolidate his rule through the systematic purging of perceived or potential enemies.

His paranoia, coupled with a desire for complete control, led to a political climate characterized by widespread suspicion and fear.

Stalin expanded the use of political repression tools, including censorship, surveillance, propaganda, show trials, executions, and, importantly, forced labor camps or gulags.

Stalin believed that reeducation through labor could transform counterrevolutionaries into useful members of Soviet society.

So, in 1929, the government introduced the concept of "corrective labor" as a penalty.

This was essentially a sentence to forced labor by another name.

How did Stalin transform the gulag system?

While early labor camps under Lenin were relatively sporadic and loosely organized, under Stalin, these camps proliferated and became more formally structured.

The centralization of the camp system took place in 1930 with the establishment of the Gulag agency under the Soviet secret police, the NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs).

Stalin specifically used gulags as an instrument for achieving several strategic objectives.

Firstly, they served as a means to suppress and isolate political dissenters, 'enemies of the state', and any individual who could potentially threaten his authoritarian regime.

In essence, the gulags were a clear manifestation of Stalin's "Great Terror" policy, which sought to cleanse the Soviet society of perceived internal enemies.

Moreover, the gulags were crucial to Stalin's forced industrialization and collectivization programs.

Prisoners were used as a ready source of cheap labor, contributing to various infrastructure projects like roads, railroads, mines, and housing.

Unfortunately, these projects were often carried out in remote and harsh regions, such as Siberia.

Here the conditions were brutal and survival was precarious. The White Sea-Baltic Canal, for instance, was built entirely by gulag laborers.

Other major projects included the Moscow-Volga Canal, the Baikal Amur Mainline railway, and numerous mining operations in the inhospitable Siberian wilderness.

In the late 1930s, at the peak of Stalin's purges, the gulag population swelled. It is estimated that millions of people were incarcerated in the gulags during this time, though exact numbers remain a subject of historical debate.

Individuals were sentenced to gulag for a wide range of "crimes" – from genuine political dissent to fabricated charges, from petty theft to failure to meet unrealistic production quotas in the collective farms.

Despite this rampant expansion, the existence of gulags was largely kept hidden from the world.

The Soviet regime maintained an iron grip over information, ensuring that the true nature and scale of the gulag system remained obscured.

It wasn't until the testimonies of survivors and declassified Soviet records emerged that the world began to understand the full extent of this brutal system.

The horrifying conditions in the gulags

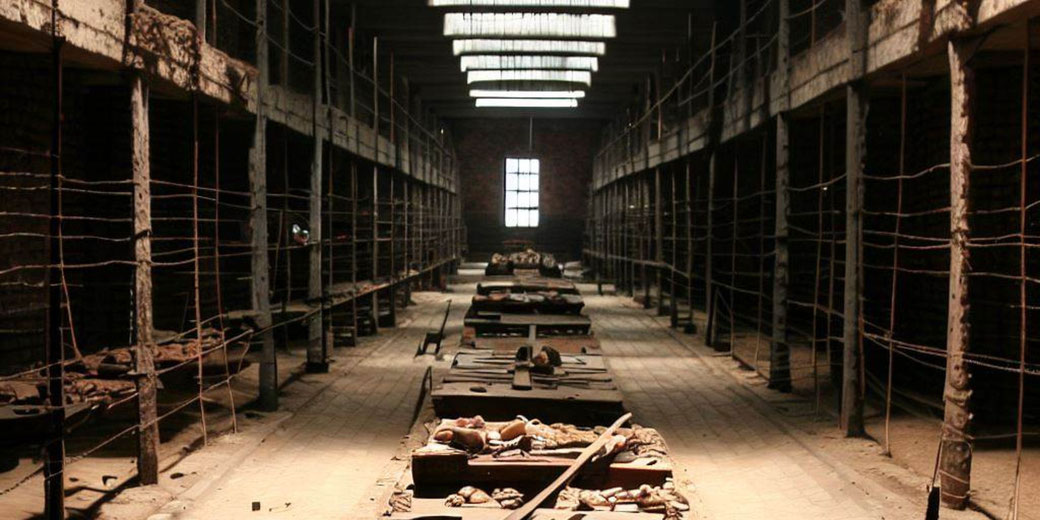

The gulags were infamous for their extremely harsh conditions, inhumane treatment, and brutal labor demands.

However, each gulag was unique in terms of its location, population, and the work that prisoners were forced to do.

The camps were scattered across the vast expanse of the Soviet Union, from the icy reaches of Siberia to the remote corners of Central Asia.

They were intentionally located in harsh and inhospitable environments. Often, they were built in places that experienced extreme with blistering summers and bone-chilling winters.

Siberian camps, in particular, were notoriously severe, where prisoners struggled to survive in temperatures that could plummet below -40 degrees Fahrenheit.

Prisoners in gulags were typically required to work long hours, often up to 14-16 hours a day, seven days a week.

The labor was grueling and often dangerous, including tasks like mining, logging, construction, and farming.

As is to be expected, safety measures were almost non-existent, which led to high rates of injury and death.

In addition, food rations in the gulags were minimal and often dependent on meeting work quotas.

Prisoners who failed to meet their quotas received less food. This pushed them into a vicious cycle of weakening strength, decreasing work productivity, and further food deprivation.

This, combined with poor sanitation, inadequate medical care, and overcrowded living conditions, led to rampant disease and high mortality rates.

Finally, the psychological toll on gulag prisoners was just as severe as the physical one.

The arbitrariness of the arrests, the absence of fair trials, and the brutal treatment led to a climate of fear and uncertainty.

Prisoners lived in constant fear of punishments, which could include solitary confinement, physical abuse, or even execution for serious infractions.

The gulags during the Great Purge

One of the most devastating episodes in the history of the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin was the Great Purge.

From 1936 to 1938, Stalin targeted various segments of society, including Communist Party members, government officials, Red Army leadership, intelligentsia, and ordinary citizens.

Anyone perceived as a threat to Stalin's rule or accused of being "counter-revolutionary" or a "traitor" could become a victim.

The reasons for arrest were often trivial or based on false charges, and confessions were frequently extracted through brutal interrogation and torture.

During the height of the Purge, the gulag population dramatically increased. Show trials, a characteristic feature of the Great Purge, were conducted, where the accused were paraded in public courtrooms, charged with fabricated crimes, and invariably found guilty.

Many of these individuals were sentenced to long terms in the gulags. Others, especially those perceived as immediate threats, were executed.

Under the infamous leadership of Nikolai Yezhov, known as the "Bloody Dwarf", the NKVD was the driving force behind the mass arrests and executions.

The terror was not limited to the prisoners alone. Fear permeated the whole of Soviet society as anyone could be accused of disloyalty.

The Great Purge ended by the late 1930s, but its impact was far-reaching. The purges decimated the Soviet political and military leadership, disrupted society, and left a legacy of fear.

Moreover, it cemented the role of gulags as a tool for political repression.

The gulags in World War Two

As the Soviet Union found itself embroiled in a brutal conflict with Nazi Germany, the gulag system was both directly and indirectly impacted.

One of the immediate consequences was the heightened demand for resources to support the war effort.

To meet this demand, gulag labor was increasingly exploited in areas such as mining for metals, logging for timber, and producing goods in factories.

In some cases, gulag inmates were even used as combatants. From 1942, facing severe manpower shortages, the Soviet authorities began to form 'penal battalions' composed of gulag prisoners.

These battalions were often deployed in the most dangerous combat situations, with promises of amnesty or reduced sentences for those who demonstrated bravery or loyalty to the Soviet cause.

Meanwhile, the war also brought about a significant influx of new prisoners into the gulag system.

As Stalin's regime became increasingly paranoid about internal threats and potential collaboration with the enemy, the purges continued.

This included mass arrests and deportations of ethnic and national groups deemed untrustworthy, such as Chechens, Crimean Tatars, Volga Germans, and many others, leading to an increase in the gulag population.

Additionally, many prisoners of war (POWs) captured by the Red Army, primarily Germans, were also sent to the gulags.

They were forced into hard labor under the same brutal conditions as other gulag inmates.

The Geneva Convention, which set guidelines for the treatment of POWs, was largely ignored.

While the end of the war in 1945 brought about a change in the geopolitical landscape, it didn't immediately transform the fate of the gulags or their prisoners.

However, the post-war years would bring about changes and challenges that eventually led to the demise of the gulag system.

The long-term consequences of the gulags

Perhaps the most immediate legacy of the gulag system lies in the human toll it exacted.

Millions of people were imprisoned in the gulags, with a significant number losing their lives due to the brutal conditions and harsh labor.

The suffering and loss experienced by these individuals and their families have been a significant part of personal and collective memories.

Even for those who survived, the scars ran deep. Many former prisoners struggled to reintegrate into society due to the stigma associated with being a gulag inmate.

They carried with them the physical and psychological traumas of their experience, affecting them and their descendants for generations.

In the years following Stalin's death, the gulag system underwent significant changes, with many camps being closed down during Khrushchev's Thaw.

This period also saw a greater acknowledgment of the atrocities committed under Stalin's rule, including the abuses of the gulag system.

However, the full extent of the system was not openly discussed until the era of glasnost under Gorbachev in the 1980s.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.