How bad was hyperinflation in Germany in the 1920s?

Hyperinflation in Germany during the inter-war years was a disastrous economic phenomenon which in the early 1920s and reached its peak in 1923.

During this time, the value of the German mark plummeted. It led to severe social and economic hardships for everyday Germans who struggled to afford basic necessities.

The crisis ultimately eroded public trust in the Weimar Republic and was one of the causes of its eventual collapse.

What is hyperinflation?

Hyperinflation is an extremely rapid and uncontrolled price increases in a nation’s currency.

It occurs when a country experiences inflation rates exceeding 50% per month.

As a result, the purchasing power of currency also diminishes at a rapid rate. This means that the cost of products keeps rising.

People then start to panic and lose confidence in how much items cost.

Often, this encourages individuals to hoard goods or use alternative forms of currency, such as foreign currencies.

What were the causes of Germany’s hyperinflation?

The end of World War I in 1918 left Germany in a precarious economic situation.

The Treaty of Versailles, which was signed in June 1919, imposed heavy war reparations on the country.

A staggering debt of 132 billion gold marks was placed upon Germany, which was to be paid to the Allied countries.

The primary cause of hyperinflation in Germany was the government's decision to print money to pay for war reparations; this led to inflation.

As the value of the mark decreased, the government printed even more money, creating a vicious cycle.

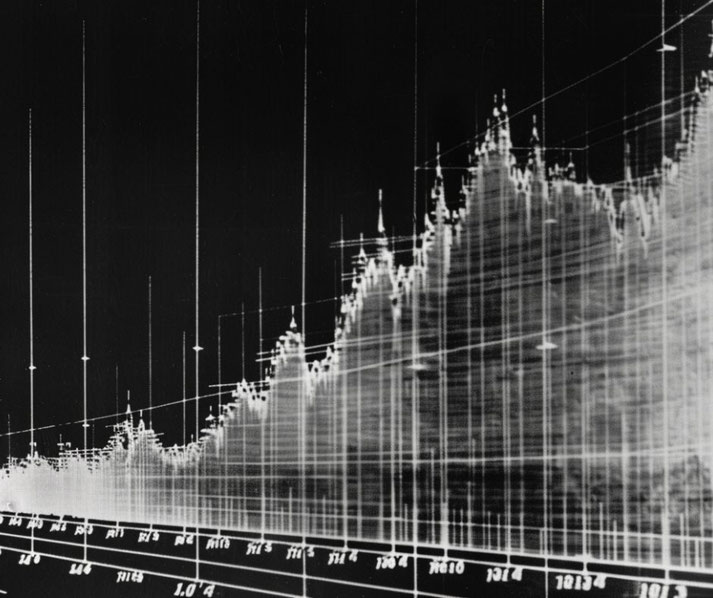

At its peak, the inflation rate reached a staggering 29,500% per month in October 1923.

This astronomical rate meant that prices of items doubled approximately every 3.7 days.

In such an environment, the German mark became virtually worthless, and people needed wheelbarrows full of money to buy basic items like bread.

What made the situation much worse was the loss of confidence in the banking system.

With prices rising rapidly, people started hoarding goods and foreign currencies.

This behavior has a further negative impact on the economy. As a result, money circulated faster as people rushed to spend it before it lost more value.

The situation worsened in 1923 when France and Belgium occupied the Ruhr region: a key industrial area.

This was in direct response to Germany's failure to make a series of reparations payments.

The occupation disrupted industrial production and trade.

The dramatic impact of hyperinflation

As the prices of everyday goods skyrocketed, the value of savings and wages eroded rapidly.

Many people were horrified to see their life savings becoming worthless overnight. Panic began to spread.

Workers demanded higher wages, but these increases could not keep pace with the soaring cost of living; consequently, some families faced poverty and hunger for the first time in their lives.

The middle class, which had traditionally been the economic backbone of German society, was particularly hard hit.

Their savings vanished, and many faced financial ruin. This erosion of middle-class wealth contributed to a sense of betrayal and disillusionment with the Weimar Republic.

Businesses also faced their own challenges as the cost of materials and production became unpredictable.

As business confidence faltered, the economy as a whole suffered from instability.

How did the government try to fix the problem?

In response to the hyperinflation crisis, the German government took several measures to try and stabilize the economy.

One of the first steps was the introduction of a new currency, the Rentenmark in November 1923.

This currency was backed by real estate and industrial assets, and they hoped it would restore confidence in the monetary system.

The Rentenmark replaced the old Papiermark at a rate of one trillion to one: effectively wiping out the hyperinflation.

Additionally, the government implemented the radical Dawes Plan in 1924. This restructured the war reparations payments.

It also provided loans to the German economy from foreign investors, mainly from those in the United States.

This plan actually helped to stabilize the currency and encouraged economic growth.

The aftermath and consequences of this period

The stabilization efforts, while successful in halting the inflation, left the country heavily reliant on foreign loans, particularly those from the United States.

This dependency became a critical vulnerability during the Great Depression.

As a result, it led to another economic crisis when those loans were called in.

The Nazi Party, in particular, capitalized on the economic despair and national humiliation.

They used it as a platform to gradually gain popular support. Ultimately, the hyperinflation episode played a pivotal role in the rise of Adolf Hitler.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.