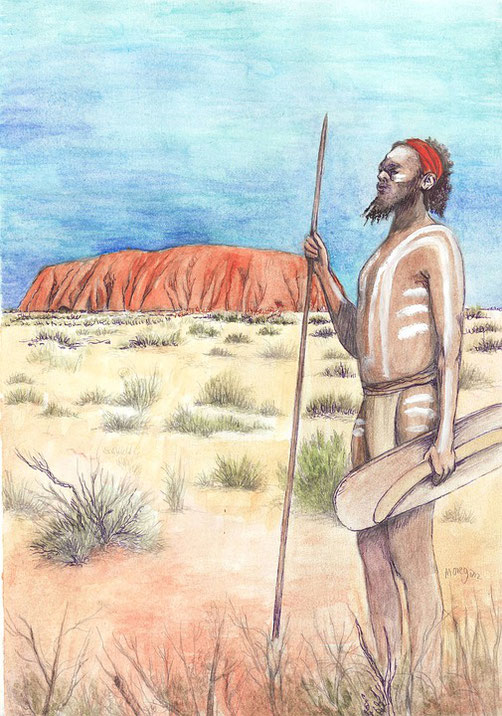

Australian First Nations leaders who fought against European colonization

As European colonists began expanding across Australia, they came into constant conflict with the First Nations people.

Various strategies were employed to address the cultural conflicts, including agreements, alliances, corruption, and theft.

Nonetheless, some First Nations warriors opted to resist and defend their ancestral territories. The efforts of these Indigenous leaders were part of the larger Frontier Wars (1788-1934), a prolonged period of violent resistance by various First Nations groups across Australia against European encroachment and dispossession.

Pemulwuy (1750 - 1802)

Pemulwuy was a Bidjigal man of the Darug nation near Sydney. He was a respected elder in his community when the British settlers arrived, with some sources indicating that he may have been a carradhy, meaning 'clever man', in his tribe.

In 1790, at Port Jackson, Pemulwuy hurled a spear at John McIntyre, an assistant to Governor Phillip.

McIntyre succumbed to the injury, prompting Phillip to dispatch soldiers in retaliation. Despite an extensive search, they failed to find Pemulwuy or his people.

Pemulwuy’s actions gained widespread support from the Eora Nation, as he became a central figure of resistance against encroaching British settlers.

Starting in 1792, Pemulwuy led his First Nations warriors in a guerrilla campaign against the European colonists.

This campaign included assaults on settlers, arson, and food theft. The conflict reached its peak with the Battle of Parramatta in March 1797, where Pemulwuy commanded a force of 100 local warriors against the Parramatta settlement.

During the conflict, Pemulwuy was shot approximately seven times, and at least five of his warriors were killed.

Captured by the colonists, Pemulwuy was taken to their hospital for treatment. Nevertheless, he managed to escape while there.

After further guerrilla attacks at colonial sites, the new British governor, Philip King, offered a cash reward for anyone who could find and kill Pemulwuy.

King also made it legal for settlers to kill any First Nations people seen near Parramatta.

Pemulwuy was finally caught and killed by Henry Hacking on 2 June 1802.

After this, Pemulwuy's head was sent to England for study.

Musquito (1780 - 1825)

Musquito was another resistance leader from the Sydney area. He was born at Port Jackson around 1780, and by 1805, had participated in guerrilla attacks on colonial settlements at Hawkesbury.

He was captured and imprisoned at Parramatta, and as a punishment for his destruction of property, was sent to Norfolk Island in 1813.

He remained a prisoner there for eight years, and then was sent further away, to Launceston in Tasmania.

However, by 1817, Musquito had become an asset to the colonial authorities, serving as a tracker.

His extensive knowledge of the native bushland proved invaluable in the pursuit of bushrangers.

Then, in the 1820s, Governor George Arthur implemented a series of policies in Tasmania that escalated conflicts with the Indigenous population, culminating in a series of violent confrontations that saw Musquito take up arms once more.

So, Musquito left the European settlements and established connections with the nearby First Nations communities.

Using his prior experience in guerilla warfare, he led an armed group that targeted local farms between 1823 and 1824, committing theft and causing the deaths of several settlers along Tasmania's east coast.

During one raid in 1824, Musquito was wounded and captured again. He was charged with murder and hanged at Hobart in 1825.

Windradyne (1800 - 1829)

Windradyne, whose name means 'strong', was a warrior from the Wiradjuri people in central New South Wales.

He became the most famous warrior leader during the Bathurst War of 1824.

British colonists continued to expand from Sydney Cove, and under the governorship of Lord Brisbane, there was a concerted effort for settlers to reach the Blue Mountains.

This further expansion displaced local groups from their traditional hunting grounds, leading to competition between both cultures for the same land.

In this setting, Windradyne emerged as a formidable guerrilla warrior leader, employing hit-and-run raiding tactics against settlers.

In December 1823, two European stockmen were slain, and it was presumed that Windradyne had orchestrated these attacks.

Subsequently, the governor dispatched military forces in pursuit of him. Ultimately, they apprehended Windradyne and imprisoned him for one month in Bathurst.

After his release, Windradyne continued attacking the colonists in response to reports that First Nations women and children had been killed by stockmen in the Wyagdon Ranges.

In response to the escalating violence, Bathurst was declared to be under martial law by the governor in 1824.

This meant that settlers were allowed to use lethal force against Indigenous people.

Also, a reward was offered for the capture of Windradyne. However, despite many attempts, they were never successful.

During an annual meeting with local First Nations people in Parramatta, the Governor was approached by Windradyne and received an official pardon for his actions.

Following his pardon, Windradyne no longer participated in further clashes against the Europeans, and eventually died following a battle with another First Nations group.

Yagan (1795 - 1833)

Yagan, a First Nations resistance leader, hailed from Western Australia. Born around 1795, he was a member of the Whadjuk people of the Noongar nation, situated just south of Perth.

At the property of Archibald Butler, a colonist, a young First Nations boy was fatally shot, prompting Yagan to retaliate by spearing one of Butler's servants to death.

In 1832, Yagan was arrested and charged with murder. He spent six weeks incarcerated on Carnac Island before he successfully fled with two fellow inmates. Together, they stole a boat and returned to the mainland.

Despite the authorities being dispatched to recapture him, Yagan remained free, and rumors of his ability to elude capture spread rapidly.

However, Yagan was eventually caught in an ambush by William and James Keates in 1833, which resulted in his death.

Like Pemulwuy before him, Yagan's head was sent to England and was only returned to Australia in 1997.

On year after Yagan's death, the Pinjarra Massacre of 1834 occurred when government forces launched a deadly assault on a Noongar camp.

Jandamarra (1873 - 1897)

Hailing from Western Australia, Jandamarra belonged to the Bunuba nation, located near the Kimberley, and was born around 1873.

He worked as a station hand alongside Europeans and had a reputation as a gifted horse rider. He later returned to his homeland, reintegrating into traditional society.

Later, Jandamarra was accused of stealing sheep by colonial authorities, and he was arrested.

However, Jandamarra struck a bargain with the local police to have his charges dismissed in exchange for caring for their horses.

His tracking abilities were so well respected that he subsequently became employed by the police in this capacity.

Regrettably, this involved him predominantly in the pursuit and capture of other First Nations individuals.

The Bunuba nation's elders confronted Jandamarra and made him choose between remaining as part of his people or being absorbed into European society.

As a show of his loyalty to the Bunuba, Jandamarra took the life of Constable Richardson while he slept, and then set free the First Nations people who were imprisoned.

Over the next three-year period, Jandamarra led tribal warriors in attacks against the settlers.

Jandamarra’s knowledge of Western firearms, which he had gained during his time working with police, gave him and his Bunuba warriors a tactical advantage in several skirmishes.

He commanded around 50 men at the Battle of Windjina Gorge, in which Jandamarra was wounded.

He had set up a hideout at Tunnel Creek, which had an extensive cave system in Bunuba country.

During his final months, it allowed him to evade colonial authorities.

Then, after an attack on his former police station in 1897, he retreated back to Tunnel Creek, where he was finally shot and killed by another Indigenous tracker, named Micki, who was working for the police.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.