What was Japan like during the Edo Period?

The Edo Period was a period of Japanese history which extended from AD 1603 to 1868. The era was named after the capital city of Edo, now known as Tokyo, which was a bustling urban hub and became the seat of power.

It is also known as the Tokugawa Period, which refers to the ruling shogunate family of Tokugawa Ieyasu, who seized power around 1600.

The first Tokugawa shoguns

The Tokugawa shogunate was officially established at the beginning of the Edo Period, after Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated the last supporters of the Toyotomi clan, led by Ishida Mitsunari, in the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.

The second and third shoguns were the direct descendents of Tokugawa Ieyasu: his son, and then his grandson.

The second Tokugawa shogun was Tokugawa Hidetada who took power in 1605 at twenty-six years old.

His father, Tokugawa Ieyasu, was retired by this stage, but still wielded power until his death in 1616.

Tokugawa Ieyasu was famous for being a shrewd and sometimes ruthless politician and military leader, but his son Hidetada however was more peaceful.

He cared for the poor and conscripted many peasants into building roads throughout Japan.

The third Tokugawa shogunate was also held by a shogun named Iemitsu who became shogun in 1623 at the age of nineteen.

He was the son of Tokugawa Hidetada and grandson of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

He is most well-known for shutting Japan to outside influences and for being extremely isolationist, as well as persecuting the Christians.

The shogunate system

Prior to Ieyasu's ascent to power, Japan was rife with civil wars as lords vied for dominance over each other.

However, under Ieyasu's leadership, the nation experienced a significant period of peace, with minimal internal strife until the close of the Edo Period.

The shogunate system was a form of political organization where a single dictator wielded absolute power, particularly over military affairs.

To maintain their power, rulers frequently established a foundation of support by distributing benefits to various social classes, including peasants and artisans.

The Tokugawa shogunate also implemented the Sankin-kōtai system, requiring daimyos to alternate where they lived between their estates in their home domains and their mansions in Edo.

This was designed to ensure loyalty to the shogun and reduce the likelihood of rebellion.

The Tokugawa shogunate had complete control over foreign affairs and only allowed trade through designated ports on the west coast of Japan.

Travel was also regulated, with Japanese residents required to remain within their fiefs. Leaving without permission was prohibited and would result in severe punishment.

The shogunate kept the emperor in place as the head of state, but only used him for official matters such as addressing foreign dignitaries.

As a result, the emperor was mostly a symbolic figurehead during the Edo period, with very limited political or ceremonial roles.

Instead, the shogunate did all the ruling.

Isolationism

Tokugawa Iemitsu isolated Japan from the rest of the world, fearing the nation was at risk of foreign invasion.

He was particularly concerned about the spread of Christianity and foreign trade, which he thought could erode Japanese culture.

In 1614, Tokugawa Ieyasu issued an edict banning Christianity, leading to the persecution and execution of thousands of Christians and foreign missionaries.

This led to one of the most significant uprisings during the Edo Period, kown as the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637-1638.

Oppressed peasants and Christian converts in Kyushu revolted against heavy taxation, which led to a brutal suppression by the shogunate.

As a result, in 1639, Tokugawa Iemitsu formalized Japan's isolationist policy known as Sakoku, which prohibited most foreign influence and limiting foreign trade to only a few select Dutch and Chinese merchants, who were confined to the artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki.

As part of this, the shogunate enforced such stringent policies that Japanese ships venturing too near to foreign vessels risked being barred from returning to Japan.

Japanese people were banned from engaging in overseas trade and the shogun limited their access to foreign imports and ideas.

As a result, Japan became cut off from the rest of the world which helped bring about peace within the country.

Foreign trade was not completely banned, however. The shogunate allowed trade to take place with China, Korea and the Netherlands through non-Japanese merchants who lived in designated trading areas.

During this period, the Dutch were among the few Westerners permitted in Japan, largely due to their technological contributions.

Nevertheless, their presence was restricted to the port city of Nagasaki. In addition to trading weapons and other commodities, the Dutch introduced concepts related to manufacturing and medicine.

However, most of these goods were only available to the samurai class.

Social and political changes

In this era, the Tokugawa clan solidified its dominance over Japan, establishing a social hierarchy that would persist for centuries.

This rigid class system, enforced by the Tokugawa through numerous sumptuary laws, placed the Tokugawa clan at the apex, succeeded by daimyōs (feudal lords), warriors, peasants, and artisans.

Notably, peasants constituted 70% of Japan's population during this period.

During the Edo Period, the samurai class transitioned from professional military warriors to a distinguished social class.

Instead of dedicating their time to mastering combat skills and battle tactics, samurai members evolved into influential bureaucrats.

Indeed, numerous samurai were appointed to high-ranking positions within the Tokugawa shogunate.

Samurai studied a variety of subjects such as Confucianism and Rangaku (Dutch studies) which was a discipline that combined scientific knowledge with Western medicine and adaptations of European mechanical technology.

Rise of merchant classes

The Tokugawa government established the Kokudaka system, which calculated the wealth and power of daimyōs based on their rice production, measured in koku, where one koku was roughly enough rice to feed one person for a year.

Then, the feudal lords were required to give their samurai a fixed stipend of rice each year.

Rice could be easily stored and could be sold at the market when there was an increase in price.

However, since there wasn't a lot of fighting during this period, the samurai had more time and money on their hands, and the demand for goods increased.

Merchants were happy to take advantage of this opportunity because they could open shops in cities that were previously inaccessible due to travel restrictions.

The merchants also started providing services that feudal lords needed which was a good way for them to gain more power within the government class.

Eventually, the government started to change hands from feudal lords to more of a merchant-dominated government.

This enabled merchants to be considered for important roles in government without having to worry about nobles trying to overthrow them.

Popular forms of entertainment

During the Edo Period, Japan saw significant urbanization, particularly in cities like Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka, which grew to populations exceeding 1 million people, making Edo one of the largest cities in the world by the mid-18th century.

In this much more peaceful world, the samurai would spend their time practicing martial arts and playing board games, such as shogi, also known as Japanese chess.

These games were one of the main forms of entertainment among samurai and provided an opportunity for socialising with other warriors.

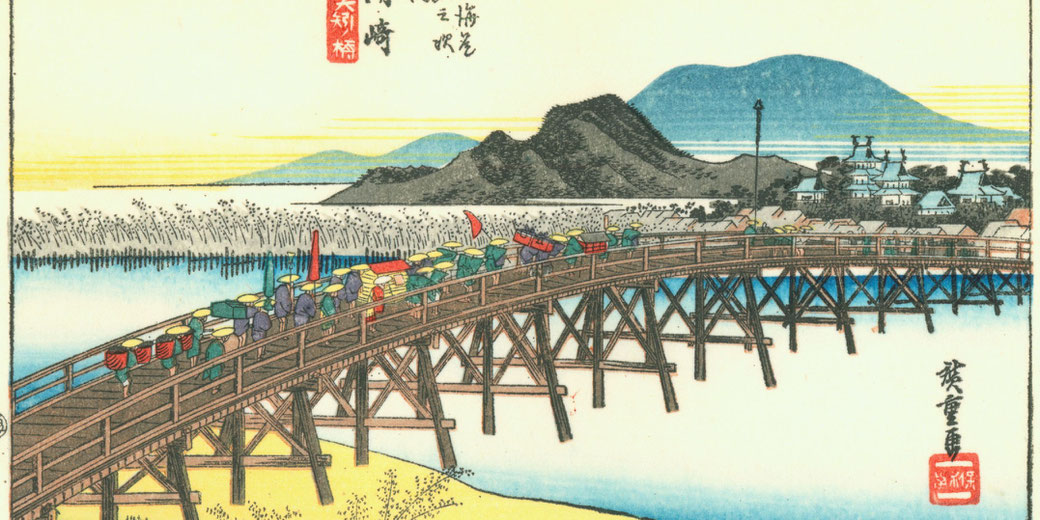

As a result, the Genroku Era (1688-1704) is often remembered as the golden age of the Edo Period, characterized by flourishing arts and culture, such as Kabuki theater, ukiyo-e woodblock prints, and the haiku poetry of Matsuo Bashō.

Theater also became a significant cultural activity for the Japanese. In the Edo Period, Kabuki evolved into a popular form of entertainment for the masses, spreading across Japan.

Performances typically centered on narratives of romance, valor, and grand exploits.

The actors, embodying various roles like samurai, physicians, and traders, were appraised based on the authenticity and skill with which they executed their parts.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.