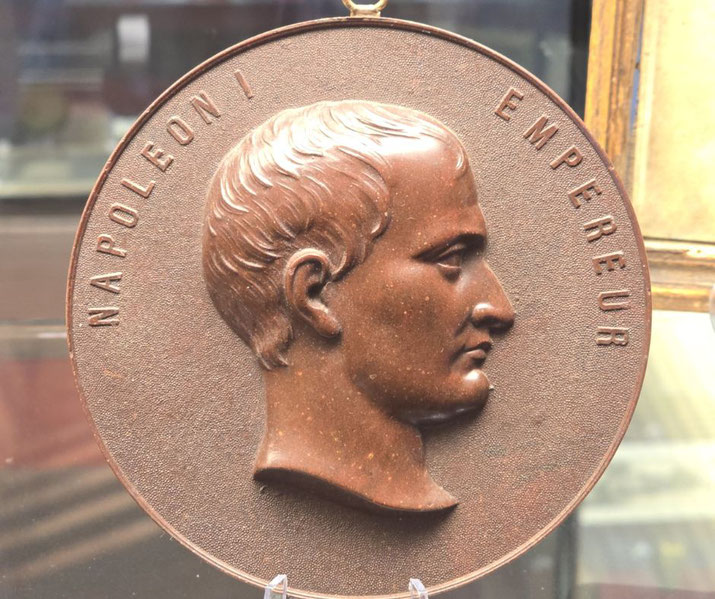

How Napoleon became the Emperor of France

Napoleon Bonaparte is, without doubt, one of the most important personalities in modern history. During his time in power, he made decisions that transformed Europe and still impact many countries across the world today.

He achieved this because he was not only was he a gifted military commander, but also became an effective (and some would say tyrannical) dictator of France.

But how did Napoleon achieve this from very obscure origins?

Napoleon's early military career

Napoleon began life as the son of minor nobility on the island of Corsica in 1769.

At 9 years old, he was sent to the prestigious École Militaire school in Paris. At the age of 16, he was the first Corsican to graduate from the institution, and he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the French army's artillery branch.

When the French Revolution broke out, he gained fame as a gifted leader of the republican armies.

His most famous early victory was capturing the port town of Toulon in December 1793 from royalist forces.

As a result of this, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general at just 24 years of age.

Over the next few years, Napoleon gained even more successes for France during his First Italian Campaign (1796-7), where he led the French army to a series of stunning victories against the Austrians.

He even forced the powerful Austrian Empire into accepting a very one-sided peace treaty (known as the Treaty of Campo Formio), which expanded French territories.

Napoleon then launched an audacious invasion of Egypt in 1798 aimed at damaging the economy of the British Empire.

Then in October 1799, he returned to Paris when he heard that the Directory government had become deeply corrupt.

With the help of two other politicians, named Roger Ducos and Emmanuel Sieyés, they seized control of the government in an event known as the Coup of 18 Brumaire on the 9th of November 1799.

Once in possession of the political life of the republic, these three men drew up plans to fix what they considered to be wrong with the revolutionary French republic.

The Constitution of Year VIII

Once the 30-year-old Napoleon and the two other men had control, they forced the old directors to resign and set up a new government known as the Consulate.

Elections for this new government were held to fill the new roles of the three 'consuls' who would hold the most power.

The three men original men (Napoleon, Ducos, and Sieyès) all intended to fill these positions. However, Napoleon was the only one of the three who succeeded, while the other two consuls were Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès, and Charles-François Lebrun.

Napoleon would be given the role of First Consul in the new government, which gave him the most power.

On the 25th of December 1799, a month after taking power, Napoleon distributed the Constitution of the year VIII, which had been created by Sieyès.

This constitution did not mention the ‘rights of man’ nor 'liberty, equality, and fraternity’ of earlier constitutions.

Instead, it outlined a range of new powers that the First Consul, who was Napoleon himself, now had.

Initially, the other consuls had significant roles, but Napoleon quickly marginalized them.

Under this constitution, Napoleon became solely responsible for assigning ministers, generals, civil servants, judges, and other important political roles.

The French people were to vote on whether the new constitution should be enforced.

The people seemed to welcome what they saw as clear and decisive leadership and overwhelmingly voted it into effect in February 1800.

The French Consulate

The French public were enthusiastic about Napoleon taking charge. They had experienced a decade of successive revolutionary governments that brought fear, death, and war on everyday citizens.

As a result, the economy and quality of life had declined over this period. Many thought that a decisive military figure like Napoleon was just the person needed in order to bring stability back to the republic.

Napoleon himself seemed to take his new position of authority seriously and began moving quickly to enforce changes upon the political and social lives of the French people.

Due to his military background, where he was used to giving orders and not having people question his authority, Napoleon did not tolerate democratic or egalitarian principles.

Instead, Napoleon wanted a government of subordinates who earned their positions based upon their personal abilities and successes: a ‘meritocracy’.

In his mind, public opinion was not an effective way to run a government. He preferred to delegate responsibility to talented and obedient people who could force his changes upon France as quickly as possible.

Achieving peace in Europe

However, Napoleon’s first concern was bringing an end to the War of the Second Coalition, which France had been fighting against the British and the Austrians since March 1799.

Over the winter and spring of 1799–1800, Napoleon reorganised his forces in preparation for a decisive counterattack.

Just as winter was ending, Napoleon marched his army into Italy and surprised the Austrian forces besieging Genoa.

A victory for the French at the Battle of Marengo on the 14th of June 1800 and another in December against the Austrians in Germany, forced the Austrians into signing the Treaty of Lunéville of February 9, 1801.

The treaty led to the confirmed French territorial gains in Europe, including the left bank of the Rhine and parts of Italy.

This only left Great Britain at war with Napoleon, but the British public was no longer behind the war effort.

Therefore, the British signed a peace treaty at Amiens on the 25th of March 1802.

For the first time in a generation, France was at peace with its European neighbours and Napoleon’s prestige increased even more.

To capitalise on his popularity, Napoleon approved a move for the French people to vote on a proposal that Napoleon should be made ‘consul for life'.

In August of 1802, the proposal was accepted.

The arrival of peace allowed Napoleon to focus on social and economic concerns, rather than military.

It was not that he stopped being interested in further expansion. Napoleon still had a strategy of further invasions in mind.

However, he knew that any further wars would best be supported by a more efficient economy back home.

As a result, Napoleon busied himself with incorporating allied states and trading partners.

For example, he incorporated Piedmont into French territories and restructured the government of the Swiss Confederation more in-line with French systems and offered compensation to the German princes.

The creation of the Napoleonic Code

Ever since 1790, the revolutionary governments had been trying to standardise the various medieval law systems of France into a more simplified and logical form.

The various wars and coups of the last ten years had meant that the project had been delayed.

However, during the peace of Napoleon’s consulate, the new code was finally published on March 21, 1804.

It was a comprehensive set of civil laws that abolished feudal privileges and established legal equality for all people.

Known today as the ‘Napoleonic Code’, it became the basis for many modern legal systems.

The French territories were divided into départements, which were overseen by prefects.

Judges were now nominated by the government, rather than elected, and they held their office for as long as necessary to ensure a fair distribution of justice.

Tax systems were also improved, and the French currency (the Franc) was stabilised.

A new banking system, known as the Banque de France, which was owned jointly by shareholders and the government, was founded.

Even education was overhauled and overseen by the government. Secondary schools were restructured along military lines and universities were provided with funding.

Becoming emperor of France

The new peace in Europe following the Treaty of Amiens had only been seen as a temporary solution by the British.

They were still wary of Napoleon and were concerned about his growing powers as First Consul.

The British government attempted to get rid of him in ways that did not require outright war.

Great Britain increased funding to French royalists, who continued to work against Napoleon within France.

Then, in 1804, Napoleon discovered a British-supported assassination plot against him, called the Cadoudal French royalist conspiracy.

In order to discourage any other attempts on his life, the First Consul ordered the police to find the ringleader and bring him to justice.

A young member of the royal House of Bourbon who was living in Baden, Germany, called duc d’Enghien, was identified as the key threat.

However, there was very little evidence that duc d'Enghien was involved in any particular attempt on Napoleon's life at all.

Regardless, police chief Joseph Fouché ordered the duke to be kidnapped and taken to Vincennes in France.

There, he was put through a speedy trial, found guilty and was executed on the 21st of March 1804.

Napoleon became paranoid about his public image and worked hard to use propaganda to encourage the French people to love and respect him.

He made sure to promote his successes, while blaming others for his failures. He carefully chose which plays were performed in the theaters of France and actively controlled the presses.

The number of approved newspapers in Paris were reduced from around 60 to about a dozen.

Napoleon started openly representing himself as a new Julius Caesar. The similarities between these two men, both talented generals and politicians, were stressed.

But one key difference remained: Caesar had become an absolute ruler as dictator of Rome, while Napoleon had not yet managed to achieve such power.

Then, Napoleon proposed that he should become the Emperor of France. The idea was put to a vote to the people of France.

However, Napoleon doubted that he would get the result he wanted, so he did not allow public debate on the topic and had Joseph Fouché actively remove dissenting voices.

In a heavily manipulated election, 3,572,329 people voted in favor, with only 2,567 against.

Napoleon held an extravagant coronation ceremony in the church of Notre Dame in Paris on December 2nd, 1804.

It cost around 8.5 million Francs and images reflecting ancient Rome were scattered throughout the event.

He had a golden laurel wreath made as his crown, which was copied from Roman examples.

Furthermore, he adopted the Roman eagle as his military icon as well.

During the ceremony, Napoleon famously took the crown from Pope Pius VII and placed it on his own head, which was meant to show that he had authority over the church.

In every way, Napoleon had become a monarch in France. Ironically, a decade after the French Revolution had beheaded their last king, the people of France were now welcoming a new one.

War of the Third Coalition

Now as emperor, Napoleon could turn his attention to declaring a new war, and to punish Britain for funding the assassination attempt against him.

He assembled over 1,000 ships along the English Channel and gathered his Grand Army near Boulogne.

Then, Napoleon encouraged Spain to join his side and they declared war on Great Britain in December 1804.

This allowed Spanish ships to join the French fleet in order to reduce the dominance that Britain’s navy held on the oceans.

Under the command of Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve, the combined French fleet set out to engage the British.

However, when the British Admiral Nelson’s fleet appeared, Villeneuve retreated to the Spanish city of Cádiz in July 1805, where they were blockaded by the British.

Napoleon was furious and ordered Villeneuve to show more courage. As a result, the French admiral tried to run the blockade.

This resulted in the Battle of Trafalgar on the 21st of October 1805. Of the 33 ships in the Franco-Spanish fleet, 21 were captured or destroyed by the British, while others were later wrecked in a storm.

In comparison, the British fleet, which only had 27 ships, suffered no losses.

While the British won a decisive victory, Nelson had been killed in the fighting. France could no longer challenge the British on the sea, so Napoleon turned his attention to land battles once more.

Battle of Austerlitz

The British had been joined by Austria, Russia, Sweden, and Naples against Napoleon.

In July of 1805, Napoleon had sent his Grand Army into Germany, where it won a resounding victory over the Austrians at Ulm in October.

On the 13th of November, Napoleon captured their capital city of Vienna.

Then, on the 2nd of December 1805, Napoleon won his greatest victory at the Battle of Austerlitz (also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors).

During this battle, 68,000 French troops defeated around 90,000 of the combined troops from Russia and Austria. 15,000 coalition men were killed and wounded, while 11,000 were captured.

In comparison, Napoleon only lost 9,000 men. Emperor Francis I of Austria and Tsar Alexander I of Russia were forced to sign the Treaty of Pressburg, in which Austria gave up all control of Italy, Dalmatia and any German territories.

The height of Napoleon’s power

By the end of 1805, Napoleon was at the apex of his career. He remained almost impossible to defeat on land, and he controlled vast sections of Europe.

His economic and social policies had increased his prestige among his own people and abroad.

However, the rest of Europe refused to accept his domination of their lands and continued to fight on.

It would be this constant need to prove himself on the battlefield that would eventually bring Napoleon’s domination over Europe to an end.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.