Tasmania's forgotten war: The conflict between British settlers and First Nations peoples

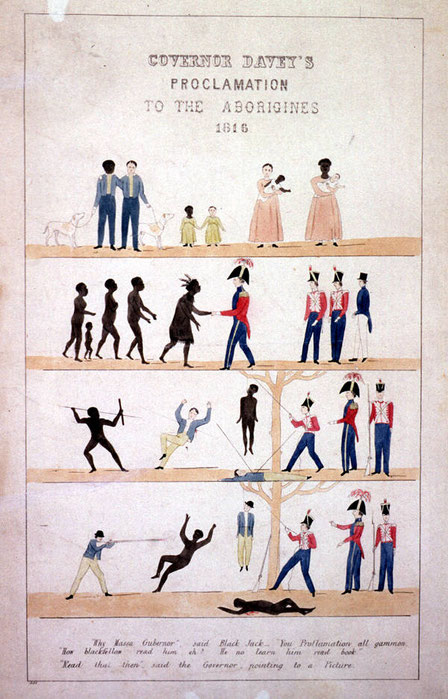

The early 1800s saw British settlers arrive in Tasmania, then known as Van Diemen's Land, sparking a conflict between two distinct cultures.

The Indigenous peoples of Tasmania, who had inhabited the region for thousands of years, did not take kindly to the displacement caused by the European arrivals.

This initiated an enduring conflict between the British settlers and the original Tasmanian inhabitants.

The causes of colonial conflict in Tasmania

The Indigenous population of Tasmania was estimated to be around 4,000 prior to British arrival in Van Diemen’s Land began in 1803 and the establishment of a penal colony near Hobart.

As the colonisation of Van Diemen's Land spread, a number of 'frontiers' developed and changed over time.

A 'frontier' is a line or border separating two regions. As British settlers moved further inland, the frontier line encroached on lands inhabited by First Nations peoples, leading to conflicts.

The colonial frontiers were always changing and, as a result, were poorly policed.

As it was not always clear which areas were under British control, it created 'unofficial frontiers', that drew people seeking a life without legal limitations, including adventurers, entrepreneurs, and petty criminals.

Beyond the frontier, the First Nations people often lacked awareness of the European settlers' rules.

Local groups struggled to differentiate between official and unofficial boundaries, and whether individuals were abiding by British laws or acting unlawfully.

Nevertheless, there were instances of neutral interactions as both cultures endeavored to comprehend the possibilities of coexistence.

From 1804 to 1824, records indicate that colonists and traditional owners engaged in trade, with First Nations people desiring items such as tobacco, tea, flour, and hunting dogs.

However, due to cultural differences, conflicts between British settlers and First Nations people were common, frequently escalating to outright warfare.

First Nations groups lacked a unified defence, as they were divided by language and complex alliances between different people groups.

Also, they lacked the sheer manpower to form large enough fighting forces to oppose the settlers.

The earliest clashes with the Europeans

The earliest details of conflict arose on Furneaux Island, following the arrival of British sealers in 1798.

These sealers aimed to profit by capturing and killing seals for their pelts.

However, this work was labour-intensive, and to increase their workforce, the sealers began abducting First Nations women from Tasmania to serve as slaves.

Enraged by these crimes, First Nations warriors attempted to fight back whenever they could, finding ways of ambushing sealers whenever they landed on the coastline.

In 1805, eight sealers were killed and 2,000 of their seal furs were burnt at Great Oyster Bay, while four sealers were killed at Cape Portland in 1824, and two more at Eddystone Point in 1828.

The first documented conflict took place on May 3, 1804, at Risdon Cove, where a kangaroo hunting group encountered British Commander Moore.

Mistaking them for attackers, Moore ordered his troops to open fire, but it is not known how many First Nations people were killed and wounded.

The 'Black War'

The 'Black War' refers to the violent clashes between British colonists and Indigenous Tasmanians from 1824 to 1830.

This conflict arose from a struggle for land dominance, with both parties vying for territories rich in wildlife such as seals and kangaroos for hunting.

An estimated 1000 First Nations people and 200 British settlers died in the fighting.

In 1824, twelve European were killed in surprise attacks from First Nations forces. The use of guerilla tactics proved effective in spreading fear through the colony.

First Nations leaders such as Mosquito and 'Black Tom' used their knowledge of European culture to increase the effectiveness of their attacks.

The conflict escalated when British soldiers arrived in Tasmania in the mid-1820s to suppress the violence.

This action, however, resulted in increased hostilities as the First Nations people perceived the soldiers as another enemy.

Consequently, many innocent civilians found themselves inadvertently involved in the confrontations, including a woman who was fatally wounded while collecting firewood.

Edward Curr, the manager of the Van Diemen's Land Company, seized control of large areas of land in 1826 from eight local people groups.

To help clear his newly acquired lands of its traditional owners, Curr encouraged the company employees to hunt and kill them.

This resulted in the Cape Grim Massacre on February 10, 1828, where four employees of Curr killed approximately 30 Indigenous people who were collecting food, and then cast their bodies off a cliff.

This inspired other indigenous leaders like Tarenorerer to rise up. She had been born around 1800 near Emu Bay, of the Tommeginne people.

Tarenorerer was then captured and sold into slavery by Indigenous kidnappers as a teenager.

She escaped in 1828 to the First Nations people at Oyster Bay, which was one of the largest indigenous groups on the island.

There, she formed a guerrilla band to resist British colonists. She became well known for her use of western firearms. Tarenorerer was finally captured in 1830 and died of influenza in 1831 while imprisoned.

The violence escalated when Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur declared martial law on the 1st of November 1828, which meant that colonists could kill First Nations people without being charged with murder.

He organised 'roving parties' of five convicts and a police constable, who were sent out to capture First Nations people.

In October 1830, a significant military operation called the Black Line was initiated. It involved 2,200 civilians and soldiers who formed moving cordons, extending hundreds of kilometres across the island.

The objective was to force First Nations people from settled districts to the Tasman Peninsula in the southeast, where they were to be permanently isolated.

The Friendly Mission

By the 1830s, the indigenous population of Tasmania was estimated to be fewer than 200 people.

In January 1830, a colonial official called George Augustus Robinson, sought to create a more positive solution to the ongoing conflict.

He was chosen to lead a 'Friendly Mission' in an attempt to bring about peace between the British settlers and First Nations Tasmanians.

He was seen as a good choice because he was sympathetic to their sufferings and keen to establish communities where the Indigenous peoples could settle down in peace.

The most famous member and leader of the Friendly Mission was Trugannini, who became a symbol of First Nations resistance and survival in the face of British colonisation.

She was eventually moved to Hobart, where she lived until her death in 1876, and is often regarded as one of the last fluent speakers of the Tasmanian languages.

The mission began in 1831, and Robinson managed to convince around 400 First Nations people to come with him to live at Wybalenna on Flinders Island, where they would be safe from the violence of the British settlers.

Gaining the trust of the First Nations people was a challenging task, and many were skeptical of Robinson's intentions.

When persuasion failed to relocate them from their ancestral lands, Robinson resorted to military force to fulfill his objectives.

Consequently, the mission was deemed successful for it succeeded in relocating a significant number of First Nations individuals from the mainland, which in turn diminished the conflicts occurring.

By the 3rd of February 1835, Robinson declared that all First Nations people had been removed from Tasmania.

However, this relocation inflicted significant harm on their indigenous culture, as those moved to Flinders Island could no longer practice their ancestral customs and traditions.

In addition, the living conditions on Flinders Island were quite severe; by 1847, only 47 of the approximately 200 relocated Indigenous people survived due to disease and malnutrition.

The long-term consequences of colonisation

The Black War had a profound impact on both the British settlers and the First Nations people of Tasmania.

It was a brutal and bloody conflict that left many dead on both sides, and it also resulted in the near destruction of First Nations culture in Tasmania.

The conflict had repercussions for Australia as a whole, demonstrating that British colonists could not coexist peacefully with the indigenous landowners.

Consequently, this prompted a shift in colonial policy, including the establishment of Native Police forces designed to help control First Nations people.

The Black War also helped to perpetuate the myth of the terra nullius – the idea that Australia was an empty land, which could be claimed by anyone who wanted it.

This myth had been used to justify colonial violence and oppression against First Nations people up until recent times.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.