The history of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy

On the morning of Australia Day in 1972, four Indigenous Australian men set up a beach umbrella on the lawn of Parliament House in Canberra, sparking one of the most significant movements in Australian history - the Aboriginal Tent Embassy.

This establishment has served as a symbol of protest and resilience for First Nations Australians for over 50 years, highlighting their fight for rights and recognition.

Background and causes

Several key events that highlighted the marginalisation and mistreatment of the Indigenous Australian people preceded the creation of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy.

In 1963, the Yirrkala petition was presented to the Australian Parliament, marking the first major step in the fight for Indigenous Australian rights.

This petition was about the Yolngu people's opposition to mining activities on their lands in the Northern Territory.

Soon, it became a wider call for an end to discriminatory practices against First Nations people, particularly around the right to own land.

Two years later, in 1965, Indigenous Australian rights activist Charles Perkins led a group of students on a bus tour—The Freedom Ride—of First Nations communities in New South Wales.

This movement aimed to expose systemic racism, such as segregation in public facilities and housing, as well as raise awareness of the poor living conditions faced by Indigenous Australian people.

The Wave Hill walk-off in 1966 was a landmark protest against the working conditions and pay of Indigenous Australian stockmen on a cattle station in the Northern Territory.

This walk-off became one of the longest strikes in Australian history, lasting eight years.

These events set the stage for the 1967 referendum, which saw over 90% of Australians vote in favour of constitutional changes to grant Indigenous Australian people equal citizenship rights.

However, these changes did not result in substantive improvements for First Nations people on the ground.

A significant blow to the Indigenous Australian rights movement came on the 27th of April 1971.

Justice Blackburn delivered a judgement in the Gove Land Rights Case (Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd), ruling that Indigenous Australian people did not have legal ownership over their traditional lands.

By 1972, Indigenous Australians made up approximately 2% of the population, yet faced disproportionately high rates of poverty, unemployment, and incarceration.

How was the Tent Embassy created?

The Aboriginal Tent Embassy was created in direct response to Prime Minister William McMahon's announcement on 25 January 1972 that his government would reject land rights claims and instead propose a system of 50-year leases for Indigenous people.

Frustrated by years of government inaction, and angered by the new development, four men decided to take matters into their own hands.

They created the Aboriginal Tent Embassy on Australia Day 1972. The four men - Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Bertie Williams, and Tony Coorey - protested this decision, demanding that the government recognise Indigenous Australian ownership of the land.

The establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy on Australia's national holiday, was deliberately symbolic, as it drew attention to the ongoing dispossession of Indigenous lands.

What began as a small structure made out of an umbrella, and later poles and tarpaulin, quickly grew into a well-organised camp.

It served as a focal point for the Indigenous Australian rights movement, attracting national and international attention.

Additionally, it provided a refuge for many Indigenous Australians who had been forcibly removed from their communities.

Gary Foley joined the Aboriginal Tent Embassy shortly after its establishment and quickly became one of its most vocal and visible leaders.

How did the Australian government respond?

On the 20th of July 1972, 150 police officers marched on the Embassy. Supporters formed a human chain around the tents, singing "We Shall Not Be Moved".

Television cameras recorded the ensuing scuffle, several arrests, and the ultimate dismantling of the tents.

The tents were erected for the second time on the following Sunday, when the number of supporters had swelled to around 200.

This resulted in another confrontation between a police force of 360 and the protestors, leading to more violence. Once again, the embassy was destroyed.

The McMahon government's refusal to recognise land rights was seen as a betrayal of the 1967 referendum's promises.

However, a turning point came on Monday the 31st of July, when around 2000 protestors gathered outside Parliament House.

This forced the government to cease their attempts to pull down the structures.

By this stage, the Tent Embassy had drawn international media coverage, including features in outlets like The New York Times.

This helped bring global attention to Australia's Indigenous rights struggles.

Later history

Gough Whitlam, who was leader of the opposition and would later become Prime Minister, visited the embassy and to acknowledge its significance and show his symbolic support for land rights.

Finally, in 1974, the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory ruled that the Aboriginal Tent Embassy could remain on the lawns of Parliament House.

So, between 1972 and 1992, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was relocated several times and faced multiple challenges, including being torn down, damaged, and attacked.

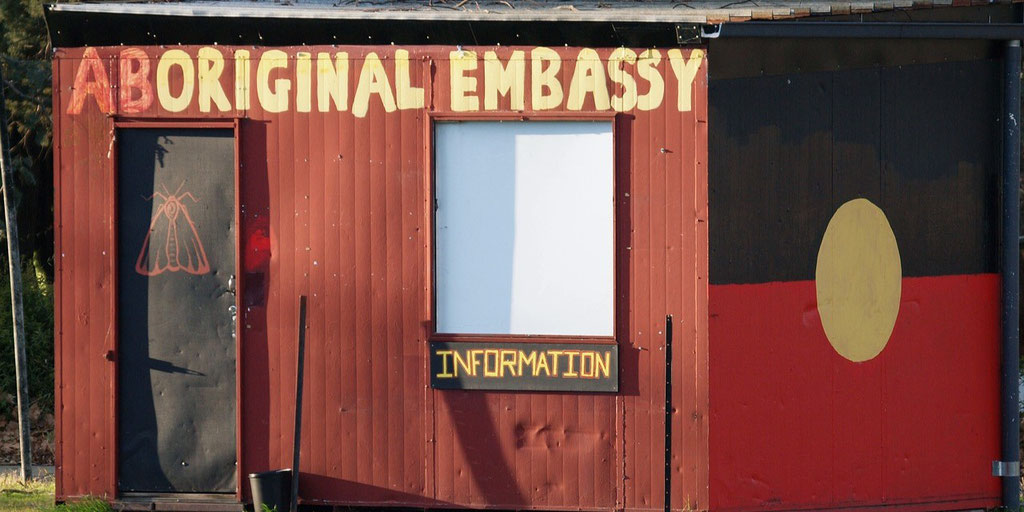

Despite this, the embassy has persisted. Since 1992, it has remained on the lawn outside of the Old Parliament House.

In 1995, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was added to the Australian Register of the National Estate.

In the 2000s, the embassy became a site of political protest against the federal government's policies on Indigenous affairs.

Why is it still important today?

The Aboriginal Tent Embassy has withstood many trials over the years but continues to stand as a powerful symbol of First Nations resistance.

Today, it serves as a stark reminder of the ongoing fight for justice and recognition that Indigenous Australians still face.

The history of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy forms a crucial chapter of Australia's narrative—one that must not be forgotten.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.