Maximilien Robespierre: The bloody tyrant behind the French Revolution's 'Reign of Terror'

When people hear the name Maximilien Robespierre, they react with either reverence or revulsion. A lawyer turned revolutionary, his impassioned speeches and unyielding principles helped shape the very core of the French Revolution, only to spiral into the infamous Reign of Terror.

His life, marked by brilliance and brutality, continues to fascinate and perplex scholars and history enthusiasts alike.

But who was the man behind the myth?

What drove him to champion the causes he did, and how did he justify the extreme measures of the Terror?

And what led to his dramatic downfall?

Robespierre's (not so) humble beginnings

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre was born in Arras, France, on May 6, 1758, to a family of lawyers.

His early life was marked by tragedy, as his mother died when he was only six years old, and his father abandoned the family shortly thereafter.

Raised by his maternal grandparents, Robespierre's upbringing was characterized by a sense of abandonment and a yearning for stability.

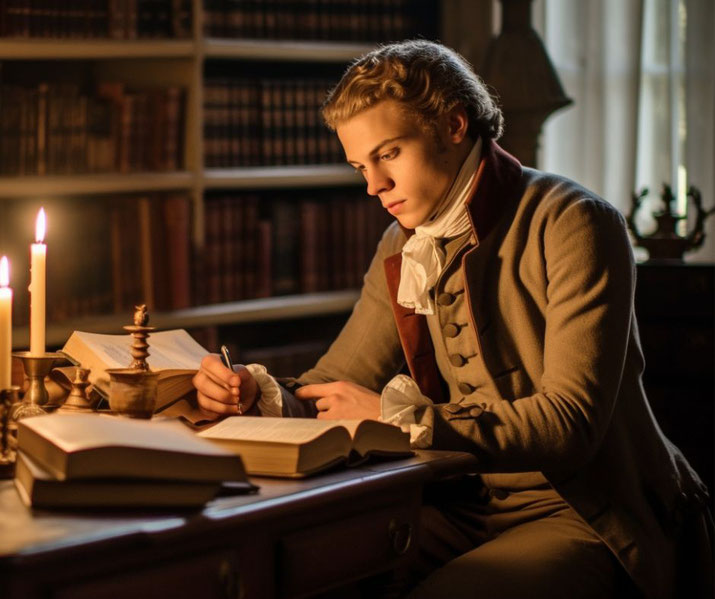

Despite these early hardships, Robespierre excelled academically. He won a scholarship to the prestigious Louis-le-Grand College in Paris, where he immersed himself in classical studies and the writings of Enlightenment philosophers such as Rousseau and Voltaire.

These thinkers greatly influenced Robespierre's developing political ideology, instilling in him a belief in the innate goodness of man and the corrupting influence of society.

Robespierre's time at Louis-le-Grand was marked by his exceptional intellect and a growing passion for social justice.

His eloquence and persuasive oratory skills were evident even at this young age, earning him accolades and recognition from his peers and teachers.

In 1781, he received a law degree from the University of Orleans and returned to Arras to practice law.

As a young lawyer, Robespierre quickly gained a reputation for his commitment to the rights of the poor and marginalized.

He often took on cases pro bono, defending those who could not afford legal representation.

His legal practice was not merely a profession but a platform for his burgeoning political ideas.

He became vocal in local politics, advocating for democratic reforms and the abolition of feudal privileges.

What were Robespierre's political beliefs?

Maximilien Robespierre's political ideology was deeply rooted in the Enlightenment ideals of reason, liberty, equality, and fraternity.

A staunch advocate for democratic principles, he believed in the inherent goodness of the common people and the necessity of a government that represented their interests.

Robespierre's political philosophy was heavily influenced by the writings of Rousseau, particularly "The Social Contract."

He embraced the concept of the general will, arguing that the collective will of the people should be the guiding force of government.

This belief led him to champion universal suffrage and the abolition of property qualifications for voting, radical ideas for his time.

His commitment to equality extended beyond political rights. Robespierre was an early advocate for the abolition of slavery in the French colonies and spoke out against racial and economic discrimination.

He believed that true liberty could not be achieved without social equality, and he worked tirelessly to dismantle the feudal privileges that had long oppressed the French populace.

Yet, Robespierre's ideology was not without its contradictions. While he espoused democratic principles, he also believed in the necessity of a strong and centralized government to guide the Revolution.

During the Reign of Terror, he justified the use of extreme measures, including mass executions, as necessary to preserve the Revolution and protect it from internal and external enemies.

His unwavering belief in the righteousness of his cause led him to view dissent as treason, a stance that would ultimately contribute to his downfall.

Robespierre's political philosophy also encompassed a moral dimension. He saw virtue as essential to the success of the Republic and believed that public officials should be held to the highest ethical standards.

His emphasis on virtue and incorruptibility earned him the nickname "The Incorruptible," though it also led to accusations of self-righteousness and fanaticism.

How he rose to power in Revolutionary France

Maximilien Robespierre's rise to power began with his election to the Estates-General in 1789, where he represented the Third Estate, comprising the common people of France.

In the early days of the Revolution, Robespierre was not a prominent figure, but his eloquence and passion quickly caught the attention of his fellow revolutionaries.

As a member of the National Constituent Assembly, he advocated for democratic reforms, including universal male suffrage and the abolition of the monarchy.

His speeches resonated with the radical sentiments of the time, earning him a growing following.

Robespierre's influence further expanded with his involvement in the Jacobin Club, a political group that became the most radical faction of the Revolution.

Within the Jacobins, Robespierre's voice became synonymous with the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

His leadership helped steer the club towards a more radical agenda, pushing for the execution of King Louis XVI and the establishment of a French Republic.

In July 1793, Robespierre was elected to the Committee of Public Safety, the de facto executive government during the most turbulent phase of the Revolution.

His role in the Committee marked the zenith of his political power. He became the driving force behind the Reign of Terror, implementing policies to suppress counter-revolutionary activities and perceived threats to the Republic.

Robespierre's rise was not without opposition. His radicalism and uncompromising stance alienated many, even within his own ranks.

Yet, his ability to articulate the aspirations and fears of the revolutionary populace, coupled with his reputation for incorruptibility, kept him at the forefront of the political landscape.

His leadership during 'The Reign of Terror'

The Reign of Terror, a period of extreme political repression and violence during the French Revolution, is inextricably linked to the name Maximilien Robespierre.

Lasting from September 1793 to July 1794, this dark chapter in French history saw the implementation of draconian measures aimed at suppressing counter-revolutionary activities and consolidating the newly established Republic.

Robespierre, as a leading member of the Committee of Public Safety, was instrumental in orchestrating the Terror.

Driven by a belief that the Revolution was under threat from internal and external enemies, he advocated for swift and decisive action.

The Law of Suspects, passed in September 1793, allowed for the arrest of anyone deemed a threat to the Republic, leading to mass imprisonments without substantial evidence.

The guillotine became the symbol of the Terror, with public executions carried out on an unprecedented scale.

King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette, and many other prominent figures, including fellow revolutionaries, were executed.

Estimates of the total number of deaths range from 16,000 to 40,000, reflecting the ferocity of the repression.

Robespierre's role in the Terror was complex and multifaceted. While he was a fervent advocate for revolutionary justice, he also sought to regulate the Terror to prevent arbitrary violence.

His push for the Law of 22 Prairial, which expedited trial proceedings and limited the rights of the accused, was both an attempt to streamline the process and a reflection of his growing paranoia.

The Reign of Terror was not without its critics, even among the revolutionaries. Many saw the extreme measures as a betrayal of the Revolution's ideals, and tensions grew within the Committee of Public Safety and the broader political landscape.

Robespierre's insistence on linking virtue with terror, his unyielding stance, and his perceived self-righteousness began to alienate allies.

Robespierre's downfall and execution

Robespierre's unwavering commitment to his principles began to alienate many of his former allies.

His insistence on the purity of revolutionary virtue, coupled with his support for increasingly repressive measures, created tensions within the Committee of Public Safety and the National Convention.

His perceived self-righteousness and intransigence further isolated him from those who had once supported his cause.

The turning point came with Robespierre's speech on July 26, 1794, in which he alluded to a new purge of deputies without naming specific individuals.

This vague threat alarmed many in the Convention, who saw themselves as potential targets.

The speech, rather than consolidating his power, sowed the seeds of a conspiracy against him.

On July 27, 1794, known as 9 Thermidor in the revolutionary calendar, Robespierre and his closest allies were arrested.

A chaotic series of events followed, including a failed attempt by Robespierre to take his own life.

The next day, he was tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal, the very institution he had helped create, and found guilty.

Robespierre's execution on July 28, 1794, was a public spectacle, met with a mixture of relief, satisfaction, and trepidation.

The guillotine, which had been the instrument of the Terror, now claimed the life of its chief architect.

His death marked the end of the Reign of Terror and ushered in a new phase of the Revolution, known as the Thermidorian Reaction, characterized by a retreat from radicalism.

Why do people argue about Robespierre today?

Robespierre's commitment to democratic principles, social equality, and revolutionary virtue has earned him admiration among some historians and political thinkers.

His early advocacy for the abolition of slavery, his push for universal suffrage, and his unwavering belief in the rights of the common people have been seen as visionary and ahead of his time.

However, Robespierre's role in the Reign of Terror has cast a long and dark shadow over his legacy.

The extreme measures he championed, the mass executions, and his willingness to suppress dissent have led many to view him as a tyrant and a fanatic.

The very principles he sought to uphold became, in the eyes of some, distorted and perverted, turning the pursuit of virtue into a reign of fear.

The dichotomy of Robespierre's legacy reflects the broader challenges and contradictions of the French Revolution itself.

He embodies the tension between idealism and pragmatism, between the pursuit of universal rights and the realities of political power.

His life and actions continue to be a subject of study, interpretation, and debate, offering insights into the complexities of revolutionary leadership and the moral dilemmas of radical change.

In modern France, Robespierre's legacy is still contested. Some see him as a champion of the people and a precursor to modern democratic socialism, while others view him as a cautionary tale of extremism and ideological rigidity.

His influence can be seen in the ongoing discussions about the role of the state, the balance between security and liberty, and the ethical dimensions of political leadership.

Internationally, Robespierre's ideas and actions have had a lasting impact on revolutionary movements and political thought.

His writings and speeches continue to be studied, and his complex legacy serves as both an inspiration and a warning.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.