Why did Japan close its doors? Understanding the Sakoku Period

Beneath the auspices of the mighty Tokugawa Shogunate, the Land of the Rising Sun withdrew into its own luminous world, severing connections with the external sphere in a move as enigmatic as it was unprecedented.

The seventeenth-century decision transformed Japan into a hermit kingdom, a unique echo of the period when the nation chose to isolate itself, shutting its doors to the fluctuating winds of foreign influence and colonial aspirations.

Yet, what drove Japan, a country teeming with a rich culture, dynamic society, and promising economy, to encase itself in a shell of solitude, like a mollusk retreating into its ornate shell?

How did this isolation shape the societal and cultural evolution within this island nation, while the rest of the world barreled forward in the throes of exploration and expansion?

What external forces eventually pried open these tightly shut doors, leading to the end of over two centuries of seclusion?

Bloody background of Japan's feudal era

To truly understand the era of Japan's self-imposed isolation, it's essential to dive into the historical context that set the stage for this dramatic shift.

The period preceding Sakoku, known as the Sengoku, or "Warring States" period (1467-1615), was characterized by incessant feudal warfare, political instability, and social unrest.

This turbulent era saw numerous daimyōs (feudal lords) grappling for territorial dominance, resulting in a fractured and tumultuous Japan.

As the dust settled from the battlefield of the Warring States, a new power emerged, offering the promise of unity and stability.

The Tokugawa shogunate, established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, succeeded in unifying Japan under a single rule, marking the beginning of the Edo period.

During this time, the country witnessed an extended epoch of peace, economic growth, and stability, starkly contrasting the chaotic years that preceded it.

The Tokugawa shogunate established a strict feudal caste system, with the shogun at the apex, followed by the daimyōs, samurai, and commoners respectively.

This hierarchy reinforced social order, ensured internal control, and further consolidated the Tokugawa's power.

The societal structure, coupled with the effective central government, allowed the shogunate to exercise immense control over the country's internal and external affairs.

It was under these circumstances, driven by a combination of internal stability and external threats, that the seeds of Japan's isolationist policy, Sakoku, were sown.

Understanding this historical context offers a glimpse into the reasons behind Japan's move towards isolation.

At a time when Europe was stretching its tendrils across the globe in a fervor of colonial expansion and trade, Japan, unified and fortified under the Tokugawa shogunate, chose a different path, pulling up the drawbridge to shut itself off from the rest of the world.

The dramatic declaration of the Sakoku Edict

The initiation of Japan's self-imposed isolation, a period known as Sakoku, occurred in stages throughout the mid to late 1600s under the shogunate of Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shogun of the Tokugawa dynasty.

The term "Sakoku" roughly translates to "closed country," and the policy was primarily enforced through a series of edicts and regulations that collectively came to define Japan's isolationist stance.

The seeds of Sakoku were planted under Tokugawa Ieyasu, Iemitsu's grandfather, who was skeptical of foreign influences, particularly of Christianity.

Concerns about religious conversion, coupled with fears of colonialism, made him wary of foreign presence.

However, it was under Tokugawa Iemitsu that these concerns hardened into a policy of isolation.

The Sakoku policy became official through a series of seclusion edicts, issued between 1633 and 1639, which restricted the movement of people and goods in and out of the country.

One of the most significant of these edicts was the "Edict of 1635," which established the prohibition of traveling outside Japan and returning in an attempt to control the spread of Christianity and limit foreign influence.

This edict was followed by others, which further enforced the restrictions by banning foreign literature, expelling foreign missionaries, and limiting the construction of large ships that could potentially be used for unauthorized overseas travel.

In 1639, the Sakoku policy was effectively solidified with the "Edict to Expel the Portuguese," which banned Portuguese merchants and missionaries, whom the shogunate viewed as the most disruptive foreign influence.

This marked the culmination of the seclusion policies, resulting in Japan's two centuries of isolation from most of the world.

The real reasons for isolation

Internal factors were critical drivers for the initiation of the isolation policy. The Tokugawa shogunate was interested in maintaining social control and political stability, particularly after the tumultuous era of the Sengoku period.

Central to this was the need to limit the power of the daimyōs, the regional lords who posed a potential threat to the shogunate.

By restricting overseas travel and trade, the shogunate could prevent the daimyōs from amassing wealth and power that might challenge the Tokugawa regime.

Religion also played a significant role in the decision for isolation. The spread of Christianity, introduced by Portuguese and Spanish missionaries in the 16th century, was viewed as a destabilizing factor.

The shogunate feared that Christianity could be used as a pretext for foreign powers to invade, as had occurred in other parts of Asia and the Americas.

Moreover, Christianity was seen as a potential threat to the established order, as it encouraged loyalty to a higher power beyond the shogun.

Externally, the specter of colonialism loomed large. The aggressive expansion of European powers, such as Spain and Portugal, into other parts of Asia was a significant concern.

The shogunate was particularly alarmed by the fate of the Philippines, which had fallen under Spanish control, with Christianity playing a substantial role in the colonization process. Japan wanted to avoid a similar fate and preserve its sovereignty.

Finally, the economic impacts cannot be overlooked. The shogunate wanted to control trade and protect local industries from foreign competition.

The policy of isolation was a way to manage the economy and prevent exploitation by foreign powers.

The dramatic impacts of the isolation

In terms of society and economy, the isolation brought about an unexpected side effect: a period of relative peace and stability known as Pax Tokugawa.

With the cessation of wars and conflicts that had plagued the country during the Sengoku period, Japan enjoyed a prolonged era of internal peace.

This peace stimulated economic growth and allowed for advances in agriculture, leading to a population increase.

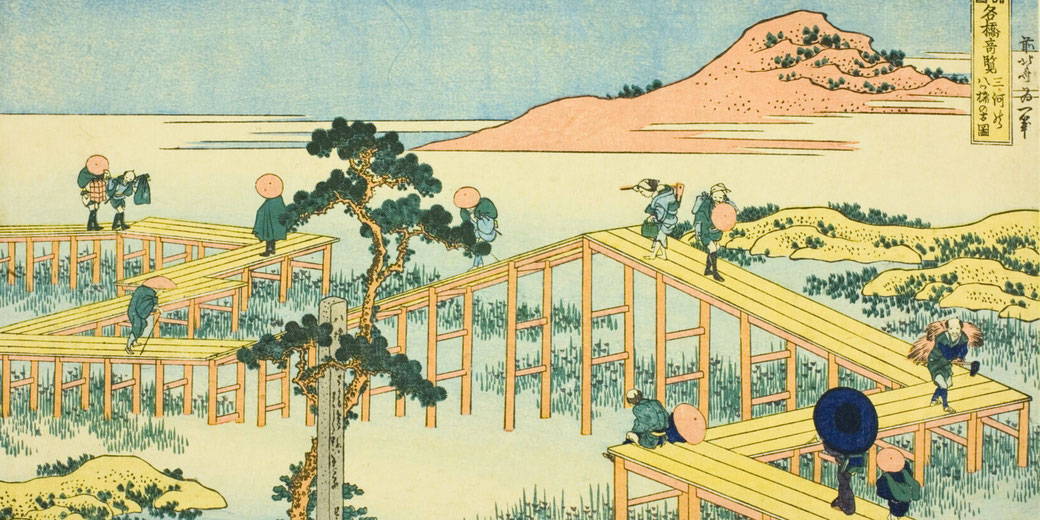

The steady political climate also allowed for a flourishing of culture and arts, with the rise of kabuki theater, ukiyo-e painting, and haiku poetry among other things.

However, the isolationist policy also meant that Japan was largely cut off from scientific and technological advancements happening in the rest of the world.

While the country developed its own unique technological solutions to various problems, it did not benefit from the rapid scientific progress seen in Europe during the Enlightenment.

On the cultural front, Japan's isolation enabled the preservation and development of unique cultural practices, untouched by foreign influences.

Traditional Japanese arts, literature, philosophy, and customs flourished, creating an enduring cultural legacy that continues to be a significant part of Japan's identity today.

While isolation allowed for these cultural and social developments, it also had its drawbacks.

By shutting its doors to the rest of the world, Japan had effectively locked itself out of the global trade and political network.

This resulted in an economy that was internally focused and self-sustaining, but also insular and resistant to change.

How rigidly was the isolation enforced?

While the Sakoku policy fundamentally transformed Japan into a "closed country," the enforcement was not absolute, and there were notable exceptions.

Despite the predominant narrative of complete isolation, Japan did maintain limited, controlled contacts with the outside world.

The shogunate allowed limited trade with specific foreign powers through designated ports.

Dejima, a man-made island in the bay of Nagasaki, was the single place of direct, albeit limited, trade and exchange between Japan and the outside world during the Sakoku period.

It was here that the Dutch East India Company was permitted to trade. The Dutch, who were seen as less threatening due to their primary interest in commerce rather than religious conversion, became Japan's window to the Western world.

Trade was also allowed with China and Korea through specific ports. Tsushima Domain was responsible for relations and trade with Korea, and the Matsumae clan handled interactions with the Ainu people and the exchange with the Russians in the north.

This controlled trade served dual purposes: it allowed Japan to obtain necessary goods and information about the outside world while maintaining the overall isolationist stance.

Enforcement of the policy varied over time and was subject to the political climate of the shogunate.

The isolationist policy was upheld by maritime restrictions prohibiting overseas travel by Japanese people and the building of large ships.

The Bakufu (the military government) also controlled incoming information, censoring and banning Christianity and Western books.

It is also important to note that despite the policy of isolation, knowledge and cultural influence did seep into Japan through Rangaku, or "Dutch Learning."

This was a body of knowledge about the Western world, including aspects of science, technology, and medicine, that was conveyed through the Dutch traders at Dejima.

These interactions, while limited, did provide a window to the outside world.

What did it take to force Japan to reopen to the world?

The resolute shell of Japan's isolation cracked open in 1853 with the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry and his "Black Ships" in Edo Bay.

Perry, representing the United States, was on a mission to open Japan to international trade and diplomatic relations, ending over two centuries of seclusion.

Perry arrived in Edo Bay (now Tokyo Bay) with a fleet of heavily armed steamships, showcasing Western technological advancements and naval power.

This display of "gunboat diplomacy" was a shock to the Japanese, who had remained largely disconnected from global industrial and military developments due to the Sakoku policy.

Perry demanded that Japan open its ports to American vessels for supplies and proposed establishing diplomatic relations.

Commodore Perry's visit was a pivotal moment in Japanese history. The demonstration of superior Western military power and the implicit threat it carried underscored Japan's vulnerability and the growing inadequacy of the Sakoku policy.

Perry's visit sparked intense debate within Japan, with factions divided over whether to maintain isolation or to open the country.

After Perry left, promising to return for a response, Japan was plunged into a crisis. Upon Perry's return in 1854, Japan signed the Treaty of Kanagawa, marking the beginning of the end of the Sakoku era.

The treaty, heavily skewed in favor of the United States, provided for the welfare of shipwrecked American sailors and opened two ports for American ships to take on supplies.

Though it did not yet allow for open trade, it was a significant crack in the previously impervious wall of Japanese isolation.

It is also important to note that despite the policy of isolation, knowledge and cultural influence did seep into Japan through Rangaku, or "Dutch Learning."

This was a body of knowledge about the Western world, including aspects of science, technology, and medicine, that was conveyed through the Dutch traders at Dejima.

These interactions, while limited, did provide a window to the outside world.

The Meiji Era: When Japan embraced the world

The ending of Japan's self-imposed isolation and the subsequent signing of the Treaty of Kanagawa sparked a period of significant change in the country, culminating in the Meiji Restoration.

As more Western nations followed the United States' lead and negotiated their own unequal treaties with Japan, discontent began to brew within the country.

These treaties, which heavily favored the foreign powers, sparked resentment among the Japanese, who felt their sovereignty was being undermined.

The Tokugawa Shogunate, unable to resist the foreign demands and maintain the country's isolation, was seen as weak and unable to protect Japan's interests, leading to its loss of credibility and support.

This political turmoil set the stage for a remarkable transformation. Fueled by the rallying cry "Sonno Joi" - "Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians" - a series of revolts led by samurais from the Choshu and Satsuma domains toppled the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868.

This marked the end of over 700 years of military rule by the shoguns and restored the emperor as the nominal head of state.

Emperor Meiji, just 15 years old at the time, was thrust into this new role, giving the name to the era that followed - the Meiji Restoration.

The Meiji Restoration marked a seismic shift in Japan's political, social, and economic structures.

It was a period of rapid modernization and Westernization, where Japan sought to learn from Western countries to protect its sovereignty and reposition itself in the world order.

The leaders of the Meiji era implemented sweeping reforms in virtually every aspect of life, from politics and economics to education and culture, aiming to transform Japan into a modern, industrialized nation.

Was the Sakoku Era a good or bad thing for Japan?

The Sakoku period and the transition to the Meiji Restoration continue to provoke reflection and debates among scholars, historians, and even within Japanese society.

These discussions delve into the merits and detriments of the isolation policy, the dramatic shift towards modernization, and their implications on Japan's national identity and its place in the world.

One perspective posits that the Sakoku period was beneficial for Japan, providing an extended period of peace, stability, and cultural development following centuries of internal conflict.

Proponents of this view argue that the isolation allowed Japan to develop a strong sense of national identity and cultural uniqueness, unaffected by external influences.

Contrastingly, critics argue that the isolation left Japan technologically and scientifically behind the rest of the world, setting it up for the unequal treaties that followed the arrival of Commodore Perry.

These critics often point out that Japan's insularity during Sakoku made the subsequent period of rapid Westernization during the Meiji Restoration more of a shock to the system, triggering societal upheavals and a sense of cultural dislocation.

The Meiji Restoration is similarly a topic of debate. While it is widely recognized as a period of extraordinary transformation that propelled Japan to the status of a world power, it also brought significant challenges.

The rapid Westernization has been criticized for undermining traditional Japanese culture and causing a loss of national identity.

Moreover, the socio-economic changes and modernization efforts during this period led to stark social disparities and conflicts, as not everyone benefited equally from the changes.

Finally, there is ongoing discussion about the long-term impacts of these historical periods on contemporary Japan.

The legacy of Sakoku and the Meiji Restoration can be seen in Japan's ongoing balancing act between maintaining its unique cultural heritage and engaging with the global community, as well as in its approach to foreign relations and national policy.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.