Why didn't America join the League of Nations?

At the end of World War I, the world was in ruins and desperate for a mechanism to prevent such a devastating conflict from happening again.

The United States, under the leadership of President Woodrow Wilson, had played a significant role in ending the war and was seen as a key player in shaping the post-war world.

Wilson had a vision for a new world order: one that would be based on democratic principles, free trade, and most importantly, collective security.

This vision led to the creation of the League of Nations.

What was the League of Nations?

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded on 10 January 1920 as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War.

It was the first international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace.

Its primary goals, as stated in its Covenant, included preventing wars through collective security and disarmament and settling international disputes through negotiation and arbitration.

However, despite President Wilson's instrumental role in the formation of the League, the United States never joined the organization.

This decision was not a simple one, nor was it universally agreed upon within the U.S.

America's role in World War One

The U.S. had entered World War I relatively late. As a result, the war had not been as devastating for the U.S. as it had been for the European powers.

So, there was a strong sentiment among many Americans that the U.S. should return to its pre-war policy of isolationism, avoiding entanglement in European affairs.

This felling was particularly strong in the U.S. Senate, which had the constitutional authority to approve or reject the Treaty of Versailles.

President Woodrow Wilson's vision

Woodrow Wilson, who was the 28th President of the United States, is now considered a visionary leader.

This is due to his vision for a post-World War I world which was articulated in his famous Fourteen Points speech, delivered to Congress in January 1918.

This speech outlined his proposals for a just and lasting peace, including open diplomacy, freedom of the seas, the removal of trade barriers, and the establishment of a "general association of nations" to guarantee the "political independence and territorial integrity" of all states.

This "general association of nations" was the seed that would grow into the League of Nations.

Ultimately, Wilson saw the League as a means to prevent future wars by ensuring collective security.

The idea was that if one member of the League was attacked, it would be considered an attack on all members, who would then be obligated to come to the aid of the attacked nation.

This, Wilson believed, would act as a deterrent to aggression and maintain peace.

In reality, Wilson's vision for the League of Nations was almost too ambitious. He envisaged a world where international disputes would be settled through dialogue and arbitration rather than war.

He saw the League as a forum where smaller nations would have a voice equal to that of the great powers, and where international cooperation would replace power politics.

What happened at the Treaty of Versailles?

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, marked the formal end of World War I.

It was negotiated among the Allied powers, with notable exclusion of the defeated Central Powers.

The treaty laid out the terms for peace, but it also contained the seeds of future international conflicts.

One of the key components of the Treaty of Versailles was the establishment of the League of Nations.

The League was intended to be an international organization that would resolve disputes between nations and prevent future wars.

The Covenant of the League of Nations was incorporated into the treaty, making ratification of the treaty synonymous with joining the League.

Opposition in the United States

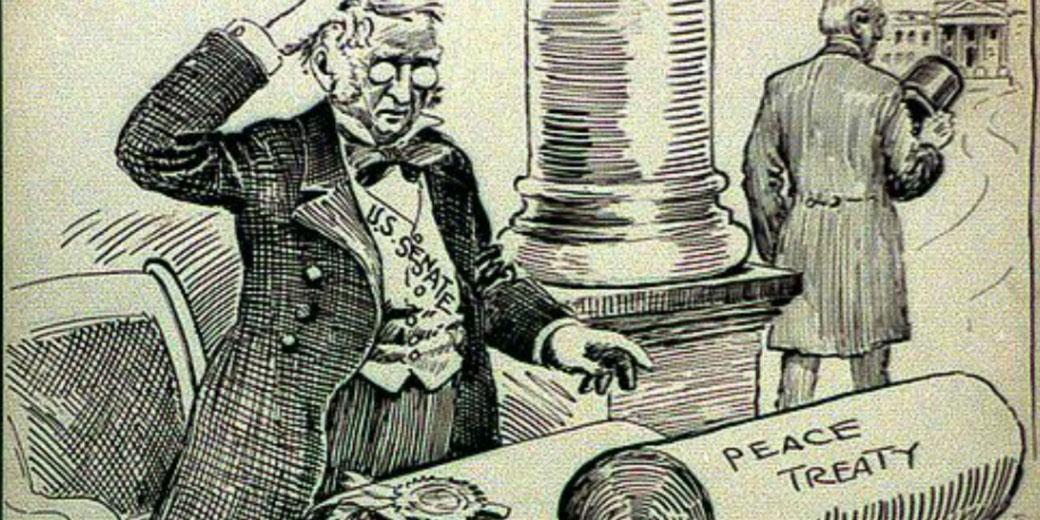

Despite President Woodrow Wilson's passionate advocacy for the League of Nations and the Treaty of Versailles, there was significant opposition within the United States, particularly in the U.S. Senate.

The Senate, as the body with the constitutional authority to ratify treaties, held the fate of U.S. participation in the League in its hands.

The opposition was led by a group of Senators known as the "Irreconcilables," who were staunchly isolationist.

They were primarily concerned about the potential loss of U.S. sovereignty and the risk of becoming entangled in future European conflicts.

They argued that the League's principle of collective security, which obligated all members to protect any member that was attacked, would force the U.S. to go to war without the consent of Congress, a violation of the U.S. Constitution.

One of the key figures in the opposition was Senator Henry Cabot Lodge. He was a Republican from Massachusetts and the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Lodge was not opposed to the idea of an international organization for peace, but he had serious concerns about the specific terms of the League's Covenant.

He proposed a number of reservations, or amendments, to the Treaty of Versailles to protect U.S. interests, but these were rejected by Wilson, who wanted the treaty ratified as it was.

The main arguments against joining the League of Nations

The decision of the United States not to join the League of Nations was underpinned by a number of arguments.

One of the primary arguments against joining was the belief that membership in the League would compromise U.S. sovereignty.

Another argument against joining was the fear of entangling alliances. This was a concern that had deep roots in American history, going back to George Washington's Farewell Address, in which he warned against permanent alliances with foreign nations.

Critics of the League feared that it would entangle the U.S. in the affairs of other countries, particularly the complex and often volatile politics of Europe.

There was also a belief among some that the League was fundamentally flawed and would not be effective in preventing future wars.

They pointed to the fact that the League had no independent means of enforcing its decisions and was reliant on the willingness of its members to act collectively.

They argued that this was an unrealistic expectation and that the League was doomed to fail.

Finally, there was a significant amount of public sentiment in favor of returning to a policy of isolationism.

Many Americans, weary from the war and the loss of life, were skeptical of becoming involved in international disputes and were concerned about the potential costs of membership in the League.

They saw the League as a potential drain on American resources and a distraction from domestic issues.

The outcome of the final votes

The fate of the United States' participation in the League of Nations ultimately came down to a series of votes in the U.S. Senate.

The first vote took place in November 1919. President Wilson, despite suffering from a stroke, had campaigned vigorously for the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, which included the Covenant of the League of Nations.

However, opposition in the Senate was strong.

Lodge proposed a number of reservations to the treaty, designed to protect U.S. sovereignty and ensure that the U.S. would not be obligated to participate in foreign conflicts without the consent of Congress.

However, Wilson, insisting on the treaty being ratified as it was, urged his fellow Democrats to vote against Lodge's reservations.

The result was a deadlock. The Senate voted on the treaty twice in November 1919, once with Lodge's reservations and once without.

Both times, the treaty failed to gain the two-thirds majority required for ratification.

The treaty was brought to a vote again in March 1920, but the result was the same.

Despite a public speaking tour by Wilson to drum up support for the League, the Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles for the final time.

The long-term consequences of the rejection

For the League of Nations, the absence of the U.S., one of the world's leading powers, was a significant blow.

The League was intended to prevent future wars through collective security, but without the participation of the U.S., its ability to enforce this principle was severely weakened.

The League struggled to maintain peace in the 1920s and 1930s, and ultimately failed to prevent the outbreak of World War II.

For the United States, the decision marked a return to a policy of isolationism. Despite its growing power and influence, the U.S. largely withdrew from international affairs, focusing instead on domestic issues.

This stance would persist until the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, which forced the U.S. to enter World War II and signaled the end of American isolationism.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.