The Bay of Pigs fiasco: The spectacular failure of the American-backed invasion of Cuba

In April 1961, a group of Cuban exiles, many of whom were trained and directed by the CIA, launched an invasion at the Bay of Pigs with the goal of toppling Fidel Castro’s government.

The operation collapsed within three days and publicly humiliated the Kennedy administration, but it also forced Cuba into a much closer alliance with the Soviet Union.

Why was America so concerned about Cuba?

American fears over Cuba had grown rapidly among many US officials after Fidel Castro’s revolutionary forces had seized power in January 1959.

After he had removed supporters of Fulgencio Batista, Castro introduced sweeping land reforms through the Agrarian Reform Law of May 1959 and began nationalising key industries.

Among the first targets were American-owned businesses, which had suffered heavy losses without receiving compensation.

As a result, the Eisenhower administration imposed economic sanctions and reduced sugar import quotas.

At the same time, US officials monitored increased Cuban ties with the Soviet Union.

Intelligence reports described the arrival of several Soviet diplomats and technicians in Havana, along with growing cooperation between the two governments.

For many Cold War planners in Washington, the possibility of a communist regime that operated just 145 kilometres from Florida triggered an urgent strategic response.

By March 1960, President Eisenhower had approved a covert plan intended to remove Castro from power.

So, the CIA began building a force of Cuban exiles that it trained in guerrilla warfare, sabotage, and amphibious landings.

Supplies came from American airbases and naval vessels, while secret training camps, which operated in Guatemala and Nicaragua, provided the training.

The most prominent camp was located at Retalhuleu in Guatemala, where CIA front companies such as Zenith Technical Enterprises, which operated out of Miami, coordinated operations in complete secrecy.

When Kennedy entered office in January 1961, preparations for the invasion had already been well advanced.

Secret plans and preparations for the invasion

The CIA selected Brigade 2506 as the main fighting force. Most of its 1,400 members had fled Cuba after the revolution and many supported the restoration of a non-communist government.

The group was commanded by José Pérez San Román, who had been an officer in the Cuban military.

Training sessions covered a wide range of combat techniques, including some specialised skills, and instructors placed heavy emphasis on discipline and coordination and insisted on strict secrecy during training exercises.

For air support, the CIA prepared a fleet of aging B-26 bombers, painted with Cuban markings to disguise their origin, and launched them from bases in Nicaragua.

Initially, planners wanted the force to land near Trinidad, where anti-Castro sentiment was strong.

However, Kennedy’s advisers believed that a landing near a large town might make American involvement too obvious.

As a result, the site was changed to the Bay of Pigs, a more isolated coastal area where defenders were expected to be sparse and the terrain would limit government reinforcements.

On 15 April 1961, CIA-supported bombers attacked Cuban airfields at San Antonio de los Baños, Ciudad Libertad, and Santiago de Cuba.

The stated goal was to destroy the Cuban air force before the main assault began.

However, the strike failed to eliminate all aircraft, and Cuban authorities captured and displayed wreckage from American planes.

To reduce diplomatic consequences, Kennedy cancelled the second wave of airstrikes scheduled for the next day.

That decision had left the invasion force particularly vulnerable to enemy aircraft during the coming battle.

How the invasion went terribly wrong

At dawn on 17 April, the main landing began. Brigade 2506 troops came ashore at Playa Girón and Playa Larga.

Almost immediately, they encountered a series of logistical and operational problems.

Poor weather disrupted navigation, coral reefs damaged supply vessels, and heavy equipment became stuck in marshland.

Several Cuban militia units responded within hours, and by mid-morning, they had linked up with regular army forces.

Without proper air support, the invaders suffered significant losses. Cuban planes attacked the beaches from the air and destroyed transport ships, which left the brigade with low ammunition and no reliable means of retreat.

Attempts to advance toward inland objectives largely stalled due to enemy fire, blocked roads, and confusion that spread among the troops.

Kennedy faced political and military pressure to commit American jets to support the mission.

However, advisers warned that direct military intervention could trigger a wider crisis, so, he refused to expand the mission.

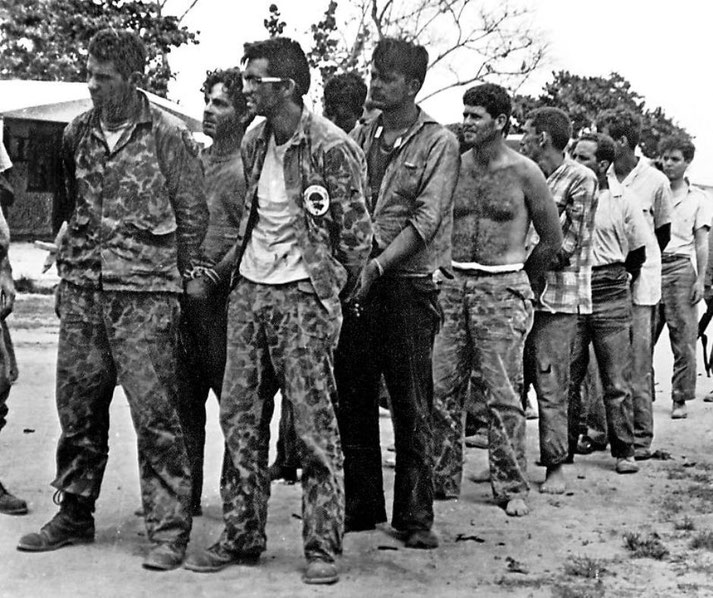

By the evening of 18 April, the invading force had been surrounded. On 19 April, the final pockets of resistance collapsed, and Cuban forces took over 1,100 prisoners.

State-run newspapers, which paraded the captured men through Havana, aimed to rally popular support around the revolution.

Months later, negotiators led by American lawyer James Donovan eventually secured the release of the prisoners in exchange for approximately $53 million in humanitarian aid, including food and medicine.

The long-term impacts of the failed invasion

Immediately after the battle, Castro used the victory to tighten his hold on power.

He removed political rivals, expanded internal security forces, and launched mass arrests of suspected opponents of the revolution.

Within months, he officially declared Cuba a Marxist-Leninist state and formalised its alliance with the Soviet Union.

For many Cubans, the invasion seemed to confirm the threat of American intervention and justified closer ties with Moscow.

In response, the Soviet Union increased its military and financial aid to the island and accelerated plans for deploying strategic weapons.

Across Latin America, the invasion triggered street protests and prompted diplomatic criticism in several countries.

Many regional leaders denounced the action as a clear breach of international law.

At the United Nations, Cuba presented captured weapons and aircraft to prove American involvement.

That evidence partly undermined US claims of plausible deniability and damaged Washington’s moral authority during Cold War debates.

Significantly, the failure had consequences that reached other countries as well as Cuba.

Khrushchev apparently interpreted Kennedy’s hesitation as weakness.

Encouraged by the outcome, the Soviet leader initiated Operation Anadyr in May 1962, authorising the placement of nuclear missiles in Cuba.

That decision led directly to the Cuban Missile Crisis, which brought the world to the brink of nuclear war and forced the United States to rethink the limits of its Cold War strategies.

Who was to blame for the disaster?

Responsibility largely rested with both the CIA and the Kennedy administration.

The agency had developed the plan based on wrong assumptions about popular resistance to Castro and had underestimated the Cuban government’s military readiness.

What is more, agency analysts had misread the situation in Cuba and had failed to expect how quickly the regime would respond.

Internal reports had wrongly predicted that widespread uprisings would erupt once the exiles landed, which never occurred.

Kennedy did not create the original plan, but he had approved its final version. His decision to relocate the landing site, restrict air support, and scale back direct military involvement had left the invasion force exposed.

At key moments, the president chose caution over escalation, which contributed to the collapse of the mission.

Later reviews of the operation criticised his failure to ask hard questions about the assumptions behind the plan.

His approval rating fell sharply among some voters in the weeks that followed, though some Americans praised him for refusing to escalate the conflict.

Within the CIA, senior figures such as Allen Dulles and Richard Bissell, who had overseen parts of the operation, were criticised.

Bissell resigned in February 1962, and Dulles was replaced by John McCone later that year following the internal investigation into the invasion’s failure.

The events had clearly shaped Kennedy’s future decisions, especially during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when he demanded greater scepticism and wider debate from his advisers and insisted on planning that matched what operations required.

The Bay of Pigs fiasco became a case study in the dangers of groupthink and secrecy, and it exposed the risks of relying on covert operations to achieve important foreign policy goals.

Many historians, such as Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., who was part of Kennedy's administration, and Peter Kornbluh, who later published extensive research on the episode that used newly released records, have used the invasion as an example of how overconfidence and poor intelligence could cause severe mistakes in Cold War strategy.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.