Who was Senator Joseph McCarthy, the architect of America's second 'Red Scare'?

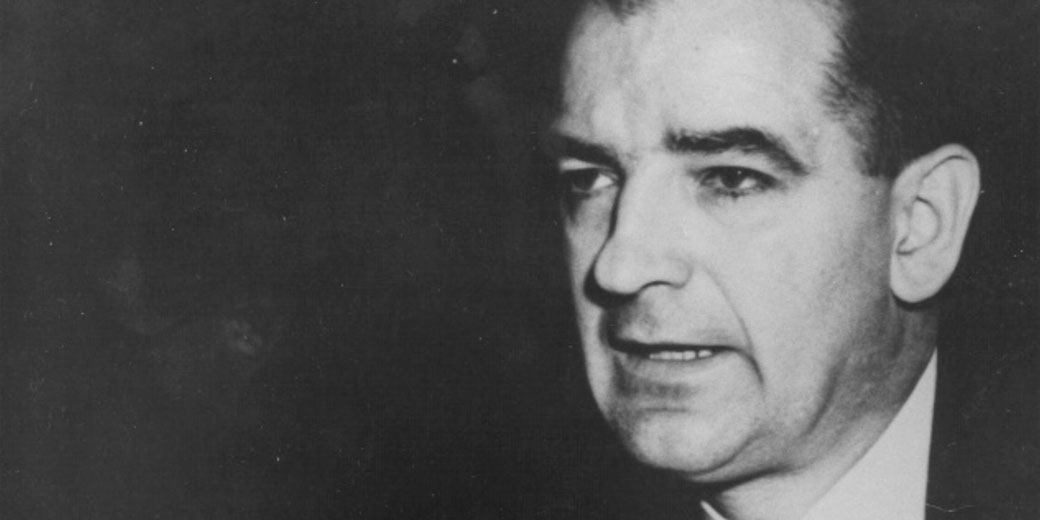

One of the most controversial and polarizing figures in American history was Senator Joseph McCarthy. McCarthy's rise to national prominence began in the early 1950s, at the height of the Cold War.

With the United States locked in a global ideological struggle against the Soviet Union, McCarthy capitalized on the pervasive fear of communism by accusing numerous individuals—ranging from government officials to Hollywood celebrities—of being communist sympathizers or spies.

These accusations, often made without substantial evidence, led to widespread paranoia, ruined careers, and a climate of fear that permeated every corner of American life.

His formative early years

Joseph Raymond McCarthy was born on November 14, 1908, in a small farming community in Grand Chute, Wisconsin.

The fifth of seven children in a devoutly Catholic family of Irish and German descent, McCarthy's early years were marked by hard work and modest means.

His parents, Timothy and Bridget McCarthy, were farmers, and young Joseph spent his childhood working on the family farm.

Despite the demands of farm life, McCarthy demonstrated an early aptitude for learning.

He completed his elementary education in a single-room schoolhouse and, at the age of 14, decided to continue his studies at a high school in nearby Appleton.

This required a daily eight-mile round trip on foot, a sign of his determination and ambition.

After graduating from high school in 1928, McCarthy initially worked as a chicken farmer before deciding to further his education.

He enrolled at Marquette University in Milwaukee, a Jesuit institution, where he studied engineering before switching to law.

Known for his competitive spirit, McCarthy excelled in his studies and was also active in various extracurricular activities, including debate and boxing.

In 1935, McCarthy graduated with a law degree from Marquette. His legal education would prove instrumental in his political career, providing him with the skills to build cases and argue them persuasively.

His military service during WWII

With the outbreak of World War II, Joseph McCarthy enlisted in the United States Marine Corps in 1942, despite being exempt from the draft due to his age and status as an elected official.

He served as an intelligence briefing officer for a dive bomber squadron in the Pacific theater.

Although he never saw actual combat, McCarthy's military service would later become a significant part of his public persona.

McCarthy's military career was not without controversy. He often exaggerated his service record for political gain, claiming to have flown on numerous combat missions when in reality his role was primarily administrative.

His most famous claim was that he was a tail gunner on a bomber, earning him the nickname "Tail Gunner Joe."

However, official records indicate that he flew twelve combat missions as an observer, not as a gunner.

Perhaps the most significant controversy related to McCarthy's military service was his use of official letterhead to write commendations for himself, which he then used in his political campaigns.

This led to accusations of impropriety and manipulation, although McCarthy defended his actions by stating that he was merely acknowledging the contributions of his entire unit.

Despite these controversies, McCarthy's military service played a crucial role in his political rise.

It provided him with a platform of patriotism and service, which he used to great effect in his campaigns.

Moreover, his military experience, real and embellished, resonated with many voters, particularly in the immediate aftermath of World War II, when the nation was still coming to terms with the sacrifices and victories of the war.

McCarthy's rapid rise into politics

Joseph McCarthy's political career began in 1939 when he was elected as a circuit judge in Wisconsin, becoming the youngest judge in the state's history at the age of 30.

However, his sights were set on higher office. In 1944, while still serving in the military, he ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination for the U.S. Senate.

Undeterred, he switched to the Republican Party and, in 1946, won a surprise victory against incumbent Robert M. La Follette Jr. for the U.S. Senate seat.

McCarthy's early years in the Senate were relatively unremarkable. He served on various committees, including the Committee on Government Operations and its Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, but struggled to make a significant impact.

That changed in 1950 when he delivered a speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, claiming to have a list of known communists working in the State Department.

Although he never produced this list, the speech catapulted him into the national spotlight and marked the beginning of the era that would come to bear his name: McCarthyism.

Over the next few years, McCarthy used his position in the Senate to launch a series of high-profile investigations into alleged communist infiltration in the U.S. government, the entertainment industry, and other sectors.

These investigations were characterized by their aggressive tactics, including guilt by association, unsubstantiated accusations, and public smear campaigns.

While they resulted in few actual convictions, they created a climate of fear and suspicion that had far-reaching effects.

The birth of McCarthyism and the Second Red Scare

The term "McCarthyism" is synonymous with the period in American history known as the Second Red Scare, which lasted from the late 1940s to the late 1950s.

This era was characterized by intense anti-communist suspicion and fear, driven by the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War and the perceived threat of internal subversion.

While McCarthy was not the sole instigator of this climate, his tactics and rhetoric amplified these fears and gave them a public face.

McCarthyism was marked by aggressive investigations and accusations without proper regard for evidence.

McCarthy, leveraging his position as chairman of the Senate's Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, targeted individuals in government, academia, and the entertainment industry, among others.

He accused them of being communist sympathizers or spies, often based on their past associations or alleged ideological leanings.

These accusations were typically made in public hearings, which were widely covered by the media and watched by millions of Americans.

The impact of McCarthyism was profound and far-reaching. Many of those accused lost their jobs and had their reputations irreparably damaged.

The fear of being targeted led to widespread self-censorship and conformity, stifling intellectual freedom and dissent.

Moreover, McCarthyism fueled a climate of fear and suspicion that permeated all levels of American society, from the halls of government to the classrooms of public schools.

Yet, McCarthyism was not without its critics. Many saw McCarthy's tactics as a violation of civil liberties and the principles of justice, including the presumption of innocence and the right to a fair trial.

These critics included prominent figures such as journalist Edward R. Murrow and lawyer Joseph Welch, whose confrontations with McCarthy during the Army-McCarthy hearings helped to turn public opinion against him.

McCarthy's downfall and censure

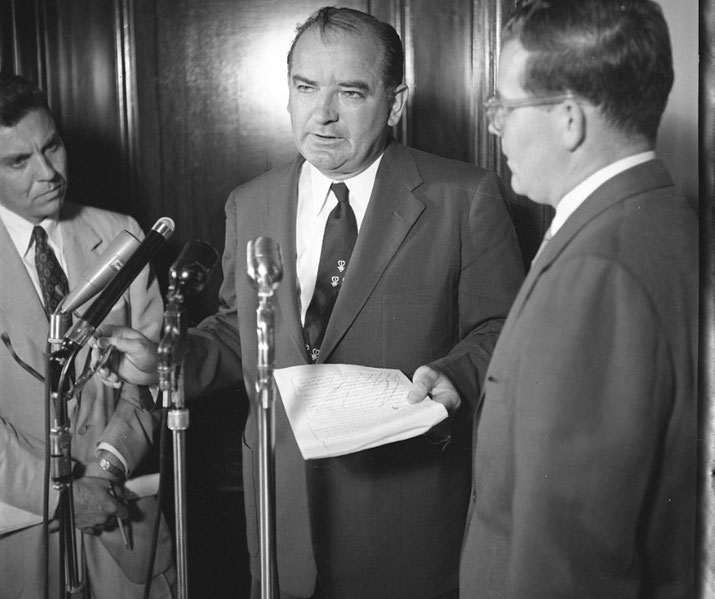

Joseph McCarthy's downfall began with the Army-McCarthy hearings in 1954. These hearings were convened after McCarthy accused the U.S. Army of harboring communists, a move that was seen by many as an overreach of his authority.

The hearings were televised, allowing the American public to witness McCarthy's aggressive and bullying tactics firsthand.

This exposure, coupled with the eloquent defense by Army's chief legal representative Joseph Welch, began to turn public opinion against McCarthy.

One of the most memorable moments of the hearings came when Welch confronted McCarthy after he attempted to smear a young associate of Welch's law firm.

Welch's response, "Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?" resonated with many viewers and marked a turning point in the proceedings.

Following the hearings, the Senate voted to censure McCarthy on December 2, 1954, effectively condemning his conduct as "contrary to senatorial traditions."

This was only the third time in American history that a senator had been censured. The censure did not remove McCarthy from office, but it significantly diminished his influence.

He was stripped of his chairmanship of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, and his accusations no longer carried the weight they once did.

His later life and death

Following his censure by the Senate in 1954, Joseph McCarthy's political influence waned significantly.

He was stripped of his powerful chairmanship of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations and was largely marginalized within the Senate.

His public speeches and accusations, which had once commanded national attention, were now largely ignored.

McCarthy's personal life also began to unravel. He struggled with alcoholism, a problem that had been present throughout much of his adult life but worsened in his later years.

His health deteriorated rapidly, and his public appearances became increasingly infrequent and erratic.

Despite these challenges, McCarthy remained in the Senate, continuing to serve until his death.

He made some attempts to revive his political career, including a bid for the presidency in 1956, but these efforts were unsuccessful.

His reputation had been irreparably damaged by his censure and the public backlash against his tactics.

On May 2, 1957, McCarthy died at the age of 48 from acute hepatitis, a condition often associated with excessive alcohol consumption.

His death was sudden and unexpected, and it marked a tragic end to a tumultuous career.

He was buried in his hometown of Appleton, Wisconsin, with full military honors, a testament to his service in World War II.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.