Ammit ‘the Great Devourer’ in Ancient Egyptian mythology

The Ancient Egyptian pantheon contained a wide range of deities and supernatural beings who were in charge over various aspects of human life and death.

Among them was a genuinely strange entity named Ammit. It, or more accurately ‘she’, was a fearsome creature who played a central role in the judgment of souls in the afterlife and, as such, was deeply feared by the Egyptians.

What did Ammit look like?

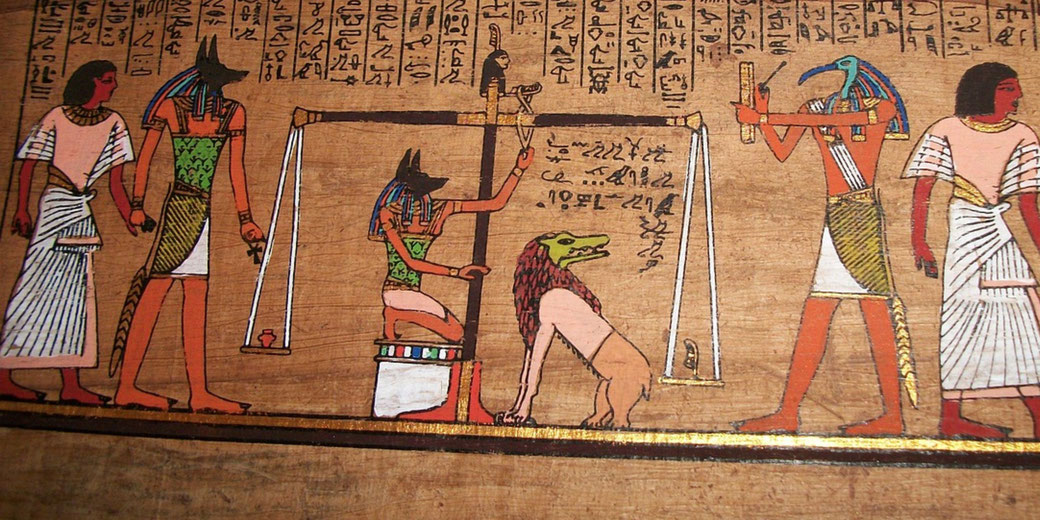

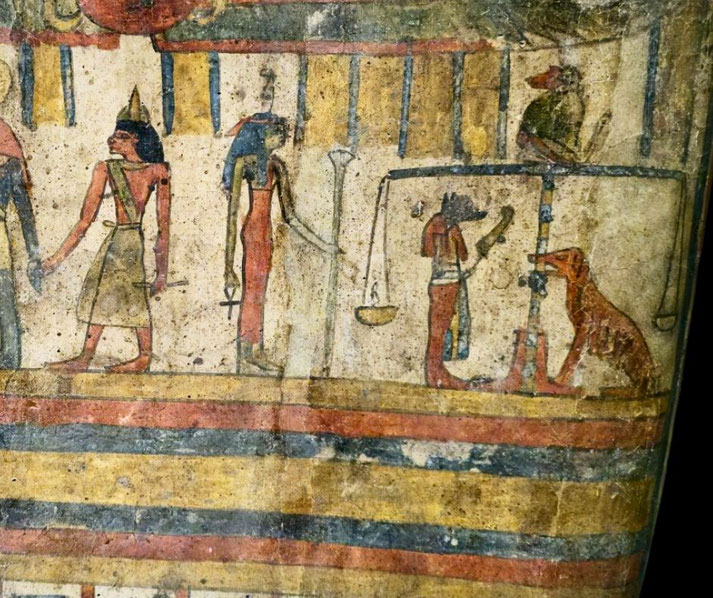

Ancient Egyptian art portrays Ammit as a hybrid creature that was a combinate of the most dangerous animals known to the Egyptians.

She is typically shown with the head of a crocodile, the front legs and upper body of a lion (or sometimes described as a leopard), and the hindquarters of a hippopotamus.

In effect, Ammit combines the three largest man-eating beasts in Egypt into one form.

On another level, these three elements carried an important symbolic meaning: she embodied complete destruction on land and water, and that no evildoer could escape annihilation even in death.

When depicted in art, Ammit is usually positioned in a crouching, attentive pose near the scales of justice, ready to spring forward.

Ammit is almost always depicted as a female demon which is sometimes called “Devourer of the Dead” or “eater of hearts”.

In the Papyrus of Ani (c. 1250 BCE), she is even depicted wearing a tricolored nemes headdress.

This was a royal striped head-cloth usually worn by pharaohs. However, some New Kingdom artwork gave Ammit a lion’s mane, despite being female.

In later periods, variations exist. For example, a Ptolemaic-era papyrus shows her standing on a pedestal with a crocodile’s head, a lion’s mane, and oddly the body of a large dog.

As is common with Egyptian art, this shows that local artistic conventions could change the forms of gods and goddesses slightly.

Ammit’s role in the afterlife

In ancient Egyptian belief, the afterlife judgment took place in a location known as the Hall of Two Truths, where the heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of Ma’at, who was the goddess of truth and justice.

For the ancient Egyptians, the heart, not the brain, was considered the place where a person’s intelligence and moral character was located.

During the weighing, the jackal-headed god, Anubis, was the guardian of the scales.

It was his job to carefully weigh the person’s heart on one side of the scale against Ma’at’s feather of truth on the other.

Thoth, the ibis-headed scribe of the gods, stood close by to record the outcome of this test. In many depictions, Osiris, ruler of the underworld (Duat), presided over the tribunal and it would be he that would ultimately decide the soul’s fate.

If the heart was found pure, which meant that it balanced with or was lighter than the feather, Osiris allowed the deceased to continue their journey into Aaru, or the ‘Field of Reeds’: a paradise of afterlife immortality.

However, if the heart was heavier than the feather, as it was weighed down by guilt and misdeeds, Ammit would devour the condemned heart.

This was considered a ‘second death’ for the soul, and a permanent destruction of one’s existence.

One whose heart was eaten by Ammit would forfeit any chance at the blissful afterlife; they would be denied entry into the Field of Reeds and instead face eternal obliteration or restless wandering in Duat.

In other words, being consumed by Ammit meant the soul became ‘soulless and trapped’ forever.

This was a fate the Egyptians feared greatly.

It’s important to note that the Egyptians did not view the judgment as hopelessly stringent.

In fact, the deceased was given opportunities to prove their worthiness before their heart might meet Ammit’s jaws.

For example, the soul can make a ‘Negative Confession’ by declaring dozens of sins it has not committed, which was meant to affirm its purity.

Only after this moral declaration would the weighing proceed. It was understood that absolute perfection was not required.

Instead, the heart needed to be reasonably balanced with virtue. Additionally, Egyptian funerary practices provided the dead with spells and protective amulets to help tip the scales in their favor.

One common protective spell that often inscribed on a scarab amulet placed with the mummy implored the heart not to betray its owner during judgment.

Ammit in funerary texts like the Book of the Dead

Ammit’s role is most famously documented in ancient Egyptian funerary literature, particularly the Book of the Dead.

This text was known to the Egyptians as the “Book of Coming Forth by Day” and is a collection of spells and illustrations designed to guide the deceased through the dangers of the afterlife and, hopefully, ensure a favorable judgment.

Ammit appears primarily in Chapter 125 of this text, which deals with the Weighing of the Heart.

In many surviving papyri, the Chapter 125 vignette explicitly shows Ammit crouched by the scales as the heart of the deceased is weighed.

This iconography seems to have become standard in the New Kingdom period, as versions of the Book of the Dead from that era onward regularly include Ammit in the judgment scene.

Interestingly, Ammit is not prominently mentioned in the earlier Pyramid Texts from the Old Kingdom or Coffin Texts from the Middle Kingdom.

At least, not by name. The concept of a soul-devouring punishment did exist, however, but it was attributed to other beings.

In certain Coffin Text spells, for instance, the god Khonsu is described as “the one who lives on hearts” or as a devourer of the unrighteous dead.

Coffin Text Spell 310 tells of hearts heavier than the feather being burned, and Spell 311 describes hearts being devoured, leaving the deceased destroyed.

These were clearly precursors to Ammit’s role. By the New Kingdom, when the Book of the Dead was compiled and widely used, Ammit had taken over this function.

The spells in different versions of the Book of the Dead do not always narrate Ammit’s actions in detail, but the threat is implicit.

Ammit’s presence in funerary texts is almost entirely as a visual and cautionary element.

There is no hymn or spell for Ammit, unlike benevolent gods, and nobody appealed to Ammit for help.

Instead, much of the Book of the Dead is structured to help the deceased avoid her.

For example, Spell 30B, which was often inscribed on a heart amulet, specifically aims to prevent the heart from testifying against the person.

This was designed to essentially cheat Ammit out of her meal. In later funerary literature, the weighing-of-heart scene (with Ammit included) continued to be depicted.

For instance, a Ptolemaic-period relief in the Temple of Hathor at Deir el-Medina shows the heart-weighing scene with Ammit sitting on a pedestal, indicating that even around 1000 years after the New Kingdom, the Egyptians still envisioned the afterlife tribunal in much the same way.

Did the Egyptians worship Ammit?

Ammit was not worshipped like a god or given offerings in temples. In fact, Egyptians did not regard Ammit as a goddess at all but rather as a demon of the underworld.

Unlike the gods and goddesses like Osiris or Isis, who had temples, priests, and cult followings, Ammit had no cult.

Some sources even suggest that Ammit’s image could be used in an apotropaic manner – that is, to ward off evil.

Just as other grotesque figures like the dwarf god Bes or the hippopotamus goddess Taweret, they were often placed as guardians to scare away malevolent forces.

Similarly, the frightening image of Ammit might have been thought to repel other evil influences.

There is evidence that she was occasionally featured on magical items or amulets as a symbol of protection through intimidation, though she herself was not directly invoked.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.