What happened when the Ancient Romans encountered Ancient China?

Ancient Rome and China, though separated by vast deserts and towering mountains, were both empires that, at their zenith, represented the apogee of human achievement in their respective hemispheres.

Many are surprised to learn that these two civilizations were aware of each other and that they interacted on some very rare occasions.

But how did these two civilizations, positioned at opposite ends of the known world, come to know of each other’s existence?

What treasures were exchanged along the Silk Road?

And how did cultural perceptions and misunderstandings shape their view of one another?

East verses west: Same or different?

Ancient Rome, with its origins traditionally dated to 753 BC, grew from a small settlement on the banks of the Tiber River to a sprawling empire that, at its height in the 2nd century AD, encompassed much of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

The Roman Empire was characterized by its advanced engineering, sophisticated political institutions, and a rich cultural tapestry influenced by the diverse peoples under its rule.

In comparison, Ancient China experienced the flourishing of the Han Dynasty, which ruled from 206 BC to 220 AD, marking a golden age of economic prosperity, technological innovation, and cultural development.

The Han Empire, with its capital at Chang’an, extended its influence across East Asia, Central Asia, and beyond, establishing a far-reaching network of trade and diplomatic relations.

The Han Dynasty is particularly noted for its advancements in astronomy, medicine, and the arts, as well as for the consolidation of Confucianism as the state ideology.

How were these empires connected?

The Silk Road, a term coined in the 19th century by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen, represents a complex network of trade routes that connected the far reaches of the East and West.

This ancient highway of commerce and culture stretched over 4,000 miles, traversing diverse terrains, including deserts, mountains, and steppes, and linking civilizations from the Roman Empire in the west to the Han Dynasty in the east.

The Silk Road was not a single road, but rather a collection of interconnected routes that facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and people across continents.

Originating in the bustling capital of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) in China, the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, the routes meandered through the Hexi Corridor, skirting the edges of the formidable Taklamakan Desert.

The journey continued through the oasis cities of Dunhuang, Turpan, and Kashgar, where merchants traded goods and exchanged tales of distant lands.

These cities, strategically located at the crossroads of trade, became thriving centers of commerce, culture, and religion, where East met West in a confluence of languages, art, and beliefs.

Upon reaching Central Asia, the Silk Road branched into several routes, each with its own challenges and rewards.

The northern route traversed the vast steppes of the Sogdian and Scythian territories, where nomadic tribes played a crucial role as intermediaries in trade.

The southern route wound through the mountainous regions of Bactria and Parthia, where the Hellenistic legacy of Alexander the Great mingled with the diverse traditions of the Iranian plateau.

The western terminus of the Silk Road lay in the Mediterranean world, where the Roman Empire, with its capital in Rome and key trading cities like Antioch and Alexandria, eagerly awaited the arrival of exotic goods from the East.

The ports of the Levant and the Nile Delta became bustling hubs of maritime trade, where Chinese silk and spices were loaded onto ships bound for various destinations across the Mediterranean Sea.

Evidence of long-distance trade before contact

The exchange of commodities between Ancient Rome and Ancient China was the lifeblood of the Silk Road, driving economic prosperity and fostering cultural enrichment along its extensive network.

The allure of exotic goods and the promise of wealth spurred merchants, traders, and adventurers to embark on arduous journeys across deserts, mountains, and steppes, bridging the distance between East and West.

Chinese silk, the eponymous and most coveted commodity of the Silk Road, held a special place in Roman society.

Its rarity, luxurious texture, and vibrant dyes captivated the Roman elite, making it a symbol of status and wealth.

The Roman appetite for silk was insatiable, and it became a staple in the wardrobes of emperors and senators, adorning the halls of palaces and the altars of temples.

The importation of silk had a significant impact on the Roman economy, leading to discussions and debates among contemporary writers about the outflow of precious metals, particularly gold and silver, to the East in exchange for this prized fabric.

Conversely, the Roman Empire exported a variety of goods to the East, enriching the markets of the Han Dynasty and beyond.

Roman glassware, renowned for its clarity and craftsmanship, was highly prized in China, where it was often buried with the elite as a symbol of status.

Precious metals, including gold and silver, were traded for Eastern luxuries, contributing to the circulation of wealth and the development of coinage in the region.

Wine, a staple of Roman culture, was introduced to the East, where it was embraced as an exotic and prestigious beverage.

When the Romans finally met the Chinese

While direct political contact was limited, several significant missions and interactions shaped the perceptions and relations between these two distant empires.

The historical accounts of these endeavors, though sometimes fragmented and ambiguous, provide a fascinating glimpse into the aspirations and challenges of cross-cultural diplomacy in antiquity.

One of the earliest and most notable diplomatic missions was initiated by the Han Emperor Wudi in 138 BC, when he dispatched the explorer and envoy Zhang Qian to the Western Regions.

Zhang Qian’s mission was primarily aimed at forming an alliance with the Yuezhi people against the Xiongnu, but his journey extended far beyond its original purpose.

Although he did not reach Rome, Zhang Qian’s explorations opened up Central Asia to Chinese influence and trade, establishing the foundations for the Silk Road and paving the way for subsequent interactions between East and West.

The Roman Empire, intrigued by tales of a powerful and sophisticated civilization in the East, also made attempts to establish contact with China.

The Roman historian Florus recorded that around 166 AD, during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, a Roman embassy arrived in China, possibly by sea.

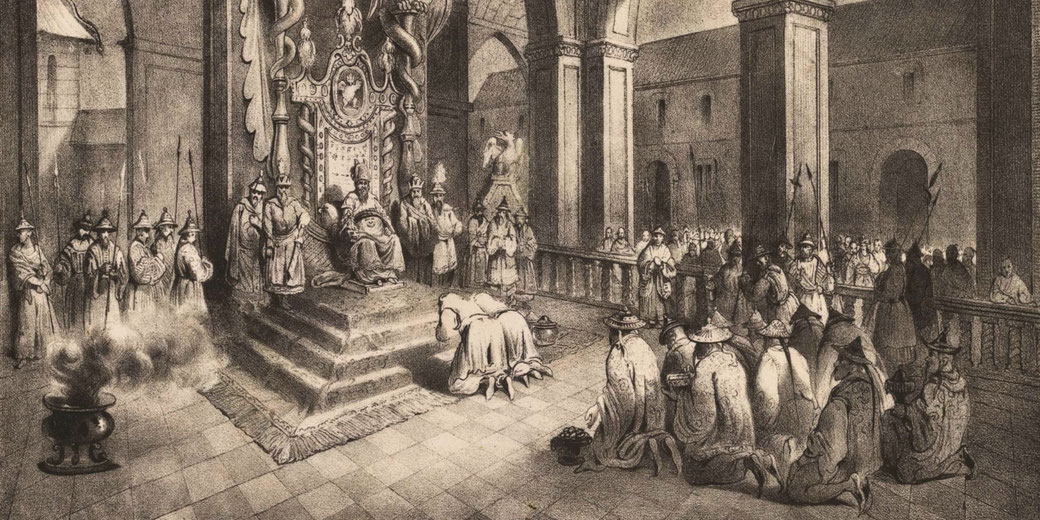

The Chinese historical text, the Hou Hanshu, corroborates this account, mentioning a group of Daqin (Roman) envoys reaching the Han court in the same period.

These envoys brought gifts of ivory, rhinoceros horn, and tortoise shell, sparking interest and curiosity about the Roman Empire among the Chinese.

Another significant interaction occurred in the 3rd century AD, during the time of the Three Kingdoms in China.

A Roman merchant named Qin Lun arrived at the court of Sun Quan, the ruler of the Kingdom of Wu.

Sun Quan was fascinated by Qin Lun’s accounts of Rome and expressed a desire to establish regular contact with the Roman Empire.

However, the vast distances and logistical challenges made sustained diplomatic relations difficult to maintain.

What did the two cultures think of each other?

The vast geographical distance, the lack of direct communication, and the reliance on third-party intermediaries contributed to a landscape where fact mingled with fiction, and reality was often embellished with elements of the fantastical.

These perceptions, shaped by fragmented information and cultural lenses, offer a fascinating insight into how these two great civilizations viewed each other and the wider world.

The Romans referred to the Chinese as the "Seres," the silk people, a name that underscored the primary association of China with the production of silk.

Roman authors such as Pliny the Elder, Ptolemy, and Florus wrote about the Seres, describing them as a peaceful and reclusive people, living at the edge of the known world.

The Chinese, in turn, referred to the Romans as the "Daqin," a term that conveyed notions of grandeur and wealth, indicative of the Chinese perception of Rome as a powerful and sophisticated counterpart in the West.

Chinese texts such as the "Weilüe" and the "Hou Hanshu" provided detailed accounts of the Roman Empire, its geography, political structure, and customs, though these were often interspersed with inaccuracies and exaggerations.

One notable misconception was the Chinese belief that the Roman Empire was a tributary state to the Han Empire.

This notion was likely fueled by the arrival of Roman envoys bearing gifts, which may have been interpreted within the Chinese tributary system framework, where smaller states presented tribute to the Emperor in exchange for protection and trade privileges.

Similarly, Roman sources contained misconceptions about the land of the Seres, often depicting it as a utopian realm of abundance and tranquility, where people lived in harmony with nature and enjoyed long lives.

The exchange of goods along the Silk Road also contributed to cultural perceptions and misunderstandings.

The Romans marveled at the beauty and fineness of Chinese silk, which was often believed to be woven from the clouds or the morning dew.

The Chinese, on the other hand, were intrigued by Roman glassware, which they considered to be a form of precious jade, attributing mystical properties to it.

But all may not be as it seems...

The exploration of the historical interactions between Ancient Rome and Ancient China has given rise to a plethora of historiographical debates, as scholars grapple with fragmented evidence, diverse interpretations, and the inherent complexities of reconstructing the past.

These debates revolve around the nature and extent of contact, the accuracy of historical accounts, and the impact of such interactions on the respective civilizations.

One central debate concerns the veracity and interpretation of historical texts that mention contact between Rome and China.

The accounts of Roman envoys reaching the Han court and the arrival of a Roman merchant at the court of Sun Quan in the Kingdom of Wu are shrouded in uncertainty.

Scholars debate whether these events represent genuine diplomatic missions or are the result of misunderstandings and misinterpretations.

The ambiguity of the sources and the lack of corroborative evidence make it challenging to draw definitive conclusions, leaving room for speculation and differing viewpoints.

Another area of contention is the economic impact of the trade between Rome and China.

The Roman historian Pliny the Elder lamented the outflow of gold and silver to the East in exchange for luxury goods, sparking discussions about the economic implications of such trade.

Scholars debate the scale of this trade imbalance and its effects on the economies of Rome and China.

The scarcity of quantitative data and the diverse nature of the economies involved make it difficult to assess the true extent and significance of the economic exchange.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.