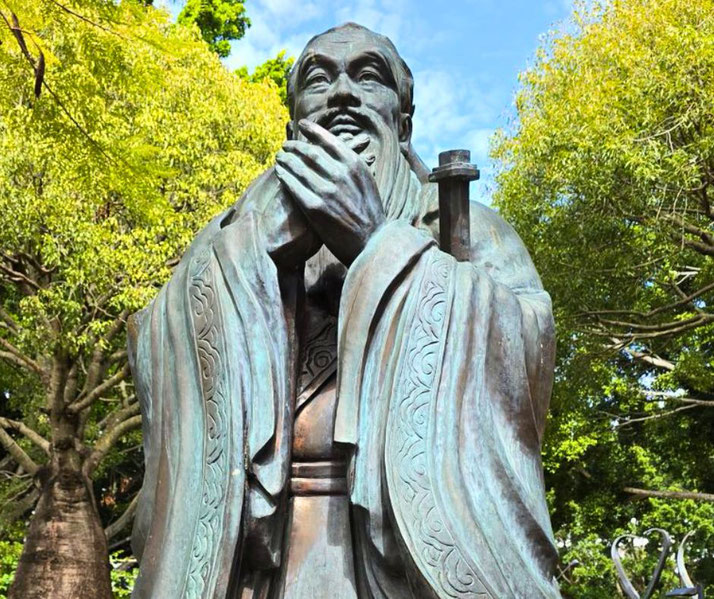

Who was the real Confucius, the greatest philosopher in Chinese history?

Few people in history have etched their thoughts and teachings into the bedrock of global culture as deeply as Confucius.

Born in the turbulent times of the Zhou Dynasty, Confucius emerged not as a conqueror or a king, but as a teacher—a sage whose wisdom continues to shape lives more than two millennia later.

His philosophy, steeped in notions of harmony, virtue, and respect, has transcended the boundaries of time and geography, influencing billions around the world and becoming a cornerstone of East Asian societies.

But who was this man we know as Confucius?

What were the foundational principles of his philosophy?

How did his teachings permeate so deeply into the fabric of Chinese society and other parts of the world?

What we know about his life

Kong Qiu, known more commonly as Confucius, was born in 551 BC in the Lu state, in what is now known as Qufu in the Shandong Province of China.

He was born into an era characterized by political strife and social chaos, commonly referred to as the Spring and Autumn period of the Zhou Dynasty.

His father, a military officer named Kong He, passed away when Confucius was only three, leaving the family in a state of hardship.

Yet, despite the early adversity, young Confucius showed a deep passion for learning and an early interest in local customs and ceremonies.

His family, though of noble ancestry, was in the lower ranks of China's class system, and as a child, Confucius experienced the life of common folks.

This early exposure to the realities of societal inequalities and corruption in the political sphere likely informed much of his later thinking about social harmony, government ethics, and personal morality.

Confucius' education was diverse, for he was known to have studied poetry and history, along with the six arts: rites, music, archery, charioteering, calligraphy, and arithmetic.

He displayed a voracious appetite for knowledge that was remarkable for his time.

His education not only prepared him for his later career as a teacher and government official but also deeply influenced his philosophical ideas.

As a young man, Confucius married and had a son and two daughters. To support his family, he worked in various governmental positions, such as managing stables and keeping books for granaries.

These experiences gave him insight into the workings of government, which would later shape his political philosophy.

How he became a famous teacher

After a series of positions in minor governmental roles, Confucius' reputation as a man of vision and knowledge began to grow.

Around the age of 30, he embarked on what would become a lifelong career as a teacher, breaking from the tradition of education being exclusive to the nobility.

His school was open to all, regardless of their social status, setting a precedent for the principle of meritocracy.

Confucius taught a broad curriculum, encompassing history, poetry, government, and propriety, among other subjects.

Confucius believed in the transformative power of education and moral cultivation.

His teachings emphasized personal virtue, ethical conduct, and proper social relationships.

He advocated for "ren" (often translated as "benevolence" or "humaneness") as the highest virtue, urging individuals to strive for moral excellence in their conduct.

Furthermore, he spoke of "li" (usually translated as "rites" or "ritual"), emphasizing the importance of propriety and ritual in maintaining social order and harmony.

The concept of "xiao" (filial piety), or the respect and duty one owes to their parents and ancestors, was also a key part of Confucius' teachings.

In his view, this respect extended beyond the family unit, influencing the relationships between ruler and subject, older and younger, and friend and friend.

He asserted the "junzi" (the ideal gentleman) as the moral exemplar, a person of high moral character, benevolent, just, and guided by a sense of duty and respect towards others.

Confucius' political philosophy centered around the idea of ethical governance. He believed that rulers should lead by moral example, inspiring their subjects to live virtuously.

He spent a portion of his life traveling through different Chinese states, trying to persuade rulers to adopt his principles of ethical leadership, but his ideas were met with mixed reception.

In his late 60s, after years of political frustration and wandering, Confucius returned to Lu.

He focused his efforts on teaching and, according to tradition, editing ancient Chinese texts.

The Analects, a collection of his sayings and discussions with disciples, compiled posthumously, became one of the central texts of Confucian philosophy.

The famous disciples of Confucius

Confucius' teachings resonated deeply with many, and he attracted a devoted group of followers.

Among these disciples, several became prominent in their own right, each carrying forward the torch of Confucian philosophy in their unique ways.

Yan Hui, Confucius' favorite disciple, was renowned for his piety and dedication to the principles of Confucianism.

Despite his premature death, Yan Hui's zeal for Confucian teachings significantly influenced subsequent interpretations of Confucian philosophy.

Zilu, another significant disciple, was known for his loyalty and bravery. His conversations with Confucius form a significant part of the Analects, contributing to our understanding of the Master's thoughts.

Zengzi, a third major disciple, was instrumental in passing down Confucian teachings to the next generations.

It is traditionally believed that he contributed to writing the "Great Learning" and the "Doctrine of the Mean", two of the four books of Confucian philosophy.

Beyond his immediate disciples, Confucius' ideas found resonance in thinkers like Mencius and Xunzi, who are often considered the second and third "sages" of Confucianism, respectively.

Mencius expanded on Confucius' principles, focusing on the inherent goodness of human nature, while Xunzi proposed a more systematic interpretation of Confucian philosophy, albeit with a contrasting view on human nature's inherent state.

These disciples and followers played a pivotal role in preserving and promoting Confucius' teachings, shaping them into an influential philosophical school.

Each added their unique perspective, helping Confucianism evolve and adapt to the changing needs of society.

Does Confucianism have any 'holy books'?

The teachings of Confucius have been preserved and passed down through several important texts, central to which are the Four Books and Five Classics.

These writings have provided the philosophical bedrock for Confucianism, and they offer critical insights into the evolution of Chinese thought and culture.

The "Four Books" include the "Analects", the "Mencius", the "Great Learning", and the "Doctrine of the Mean".

The "Analects" is perhaps the most important of these, being a collection of sayings, conversations, and anecdotes involving Confucius and his disciples.

It serves as the primary source of Confucius' views on a myriad of subjects, from moral conduct to governance.

The "Mencius" contains the teachings of Mencius, a prominent follower of Confucian thought.

The "Great Learning" and the "Doctrine of the Mean", traditionally attributed to Zengzi and his grandson Zisi, respectively, elaborate on Confucian moral philosophy.

The "Five Classics" include the "Book of Changes" (I Ching), the "Book of Documents" (Shu Ching), the "Book of Odes" (Shi Ching), the "Book of Rites" (Li Ji), and the "Spring and Autumn Annals".

These texts were supposedly edited or compiled by Confucius and encompass a wide range of topics such as history, poetry, divination, and rites.

They provide a glimpse into the intellectual tradition that influenced Confucius.

While there's ongoing scholarly debate about the authorship and authenticity of these texts, their importance in the Confucian tradition is undeniable.

They have served as essential educational tools, philosophical treatises, and moral guidebooks for centuries in Chinese society and beyond.

Confucius' profound impact on Chinese society

Confucius' teachings have profoundly shaped Chinese society, permeating its political, educational, and social spheres.

While Confucianism may not have always been the dominant ideology in China, its impact has been indelible and far-reaching.

During the Zhou Dynasty, Confucian ideas were only one among many competing philosophical schools.

However, in the following Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), Confucianism was adopted as the official state ideology.

Emperor Wu declared it the sole legal philosophy, establishing state-funded schools to teach Confucian texts.

This affirmation of Confucianism had profound implications for Chinese society, leading to the institutionalization of key Confucian principles in governance and education.

Confucianism's emphasis on hierarchical relationships and filial piety shaped societal structures and interpersonal relationships in China.

The idea of "xiao" (filial piety) solidified the family as a central unit of society, defining duties and obligations within the family structure.

Similarly, Confucius' teachings on "li" (rites) shaped social interactions and norms, promoting order and harmony in society.

The Confucian emphasis on moral character and merit also had a significant impact on China's political landscape.

The "junzi", or the ideal gentleman, became an aspirational figure for those in governance.

This led to the implementation of the civil service examination system in the Sui Dynasty (581-618 AD), which persisted in various forms until the end of the Qing Dynasty in 1912.

This examination, heavily based on the mastery of Confucian texts, offered a path to government service, embodying Confucius' idea that merit, not birthright, should determine a person's suitability for office.

In periods of political chaos and moral crisis, like the late Han Dynasty and the period of disunity that followed, Confucian teachings served as a moral compass, providing guidance on ethics and governance.

Conversely, during the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), Confucianism was suppressed, and many Confucian scholars suffered in the infamous "Burning of Books and Burying of Scholars" event.

Yet, even this brutal suppression couldn't extinguish Confucian influence, which rebounded in later eras.

How Confucian philosophy has changed over time

Neo-Confucianism represents a revival and reinterpretation of Confucian ideas that began during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), eventually gaining prominence in the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD).

This period witnessed a resurgence of interest in classical Confucian philosophy, spurred in part by the desire to articulate a comprehensive moral and metaphysical worldview that could counter the dominance of Buddhist and Daoist philosophies.

Neo-Confucian scholars sought to elaborate on and systematize Confucian teachings, incorporating insights from Buddhism and Daoism, while emphasizing their distinctness.

They delved into metaphysical and cosmological questions, which traditional Confucianism hadn't addressed as explicitly.

Zhou Dunyi, a leading figure in early Neo-Confucianism, contributed to this philosophical system's metaphysical aspects.

His work, "Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate", introduced metaphysical concepts that would become central to Neo-Confucian thought, such as the interaction of Yin and Yang and the Five Elements.

The brothers Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi were also pivotal figures in Neo-Confucianism's development.

They focused on ethical self-cultivation and inner moral sense ("liangzhi"), resonating with Mencius's emphasis on the inherent goodness of human nature.

The Cheng brothers' ideas would heavily influence Zhu Xi, arguably the most influential Neo-Confucian philosopher.

Zhu Xi solidified the canon of Confucian texts, affirming the Four Books as the core of Confucian teaching.

His commentaries on these texts became the standard interpretation for centuries, shaping education, the civil service examinations, and societal norms.

Zhu Xi presented a comprehensive philosophical system that integrated ethical, metaphysical, and cosmological elements, emphasizing the unity of human beings and the cosmos.

While Neo-Confucianism began in China, it didn't remain confined there. The philosophy spread to neighboring regions, including Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, shaping intellectual discourses and societal norms across East Asia.

How did Confucian thought conflict with other beliefs?

Confucius' teachings emerged during an era of philosophical flourishing in China, known as the Hundred Schools of Thought.

These schools offered varying perspectives on ethics, governance, and human nature, and while each was unique, they often engaged in intellectual dialogues and debates.

This diversity makes for a fascinating comparison of Confucianism with other prominent schools of thought.

Legalism, primarily associated with the philosopher Han Feizi, offered a stark contrast to Confucianism.

Where Confucius advocated for moral virtue as the basis of governance, Legalists argued for the strict application of laws and punishments, believing people were inherently self-interested and required regulation.

Legalism influenced the governance of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), a period of strict rule and suppression of other philosophical schools, including Confucianism.

Daoism, another influential school, presented a different critique of Confucian thought. Founded by Laozi and further developed by Zhuangzi, Daoism focused on living in harmony with the "Dao" (the Way) - a cosmic principle governing the universe.

Daoists criticized Confucian emphasis on ritual and societal hierarchies, advocating instead for a more natural and spontaneous way of life.

Daoism and Confucianism have often been viewed as complementary, with Daoism focusing on spiritual and metaphysical aspects of life, while Confucianism emphasizes ethical and social dimensions.

The school of Mohism, founded by Mozi, was another contemporary of Confucianism.

Mohists championed the principle of "universal love," arguing that people should care for others outside their immediate family just as they care for their kin, challenging the Confucian focus on hierarchical and familial relationships.

Mohists were also known for their advocacy of pacifism and their logical approach to argumentation.

Buddhism, while not originating in China, significantly influenced Chinese thought and culture, particularly in the post-Han Dynasty era.

It introduced concepts like karma, nirvana, and monastic life, which were distinct from Confucian principles.

The introduction of Buddhism to China spurred intellectual exchanges and debates, leading to syncretism in Chinese philosophy and contributing to the emergence of Neo-Confucianism.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.