13 greatest battles in Roman history

Throughout history, the Roman Empire has stood as an unparalleled example of the indomitable spirit and ingenuity of humankind.

For hundreds of years, Rome's legions marched across the vast expanse of the known world, leaving a trail of epic battles in their wake.

From the legendary Battle of Lake Regillus to the cataclysmic clash at Adrianople, prepare to embark on a breathtaking journey across time, witnessing the valor, cunning, and unwavering resolve of Rome's finest warriors as they fought for glory, honor, and the eternal legacy of their Empire.

What makes a battle significant?

A battle's significance cannot be solely defined by the scale of its engagement or its death toll; rather, multiple factors contribute to its lasting impact on history.

One such factor is the strategic importance of the battle, which often encompasses the territory or resources at stake, as well as the broader geopolitical implications of the outcome.

When a battle decisively shifts the balance of power between rival factions, nations, or empires, it becomes etched in history as a turning point that altered the trajectory of human events.

The Battle of Cannae, for instance, demonstrated the prowess of Carthaginian general Hannibal, and though Rome ultimately emerged victorious in the Punic Wars, the battle left an indelible mark on Roman military tactics and strategy.

Additionally, the significance of a battle is often influenced by the key figures who participate in it, their decisions and actions, and the lasting consequences of those actions.

Heroic feats, innovative strategies, and critical mistakes on the battlefield can serve as lessons for future generations, shaping the way wars are fought and altering the landscape of military thinking.

Furthermore, a battle's cultural and symbolic importance can elevate it to legendary status, resonating in the collective memory of a society for centuries to come.

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, for example, while not the largest or bloodiest battle in Roman history, marked a dramatic defeat for the Romans and a triumph for Germanic tribes, forging a deep-seated narrative of resistance and national identity.

1. Battle of Lake Regillus (c. 496 BCE)

The Battle of Lake Regillus, fought around 496 BCE, stands as a seminal event in the early history of the Roman Republic.

The battle was a result of tensions between the fledgling Roman Republic, which had overthrown its monarchy in 509 BCE, and the Latin League, a coalition of city-states in the region led by Rome's ancient rivals, the Latin city of Tusculum.

At the heart of this conflict was the deposed Roman king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, who sought to reclaim his throne with the support of the Latin League.

Lake Regillus, located near modern-day Frascati in the Alban Hills, served as the stage for this pivotal confrontation.

The Roman army was led by the dictator Aulus Postumius Albus and his Master of the Horse, Titus Aebutius Elva, while the Latin League was commanded by the exiled Tarquinius Superbus, his son-in-law Octavius Mamilius of Tusculum, and other Latin leaders.

The battle was marked by fierce and brutal fighting, with each side experiencing significant losses.

However, according to the legends, Rome was aided by the divine intervention of the Dioscuri, the twin gods Castor and Pollux, who were said to have appeared on the battlefield, bolstering the morale of the Romans and leading them to victory.

The Roman triumph at the Battle of Lake Regillus had far-reaching consequences. It effectively ended the attempts of Tarquinius Superbus to regain his throne and reaffirmed Rome's independence from Latin dominance.

The victory also paved the way for Rome's eventual hegemony over the Latin League and laid the groundwork for the subsequent expansion of the Roman Republic. The Latin League was later forced to sign the Foedus Cassianum, a treaty that established mutual defense obligations but affirmed Rome as the leading power in Latium.

While much of the battle's details are steeped in legend and myth, its significance in shaping the trajectory of Rome's early history is undeniable.

2. Battle of the Allia (390 BCE)

The Battle of the Allia, fought in 390 BCE, was a pivotal moment in the early history of Rome and a sobering reminder of the city's vulnerability.

It was during this battle that the Roman Republic faced off against the fierce Senones, a Gallic tribe led by the formidable chieftain Brennus.

The Senones had crossed the Alps and ventured into Roman territory, driven by the desire for expansion and the promise of plunder.

The Allia River, located approximately 11 miles north of Rome, became the backdrop for this decisive confrontation.

The Roman forces, led by their military tribunes, were significantly outnumbered by the invading Gauls.

In a tactical blunder, the Roman army deployed their forces in a thin line along the banks of the river, leaving their flanks exposed.

As the battle ensued, the Gauls exploited this weakness, swiftly outflanking and routing the Roman soldiers.

The devastating defeat forced the surviving Romans to retreat, allowing the Gauls to sack Rome.

The Battle of the Allia served as a wake-up call for Rome, illustrating the importance of strong military organization and the necessity of learning from past mistakes.

In the years that followed, Rome would dramatically reform its military and political structures, eventually rising to become one of the most powerful empires in history.

The memory of the defeat and subsequent sack of Rome would remain deeply ingrained in the Roman psyche, and the date of the battle, July 18, would later be known as the dies Alliensis or 'Allia Day', a day of ill omen in the Roman calendar.

3. Battle of Sentinum (295 BCE)

The Battle of Sentinum, fought in 295 BCE, was a major engagement in the Third Samnite War (298-290 BCE) and a crucial turning point in Rome's struggle to establish dominance over the Italian Peninsula.

The conflict pitted the Roman Republic, led by consuls Publius Decius Mus and Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus, against a formidable coalition of Samnites, Etruscans, Umbrians, and Gauls, who sought to resist Roman expansion.

The battle took place near the town of Sentinum, in modern-day Marche, Italy.

Facing a large and diverse enemy force of around 40,000, the Romans, who numbered approximately 36,000, deployed their legions in a massive, carefully arranged formation.

At one point, the Roman left flank, commanded by Decius Mus, began to falter under the ferocious onslaught of the coalition of warriors.

In an act of supreme sacrifice, Decius Mus performed the ritual of devotio, dedicating himself and the enemy to the gods of the underworld before charging headlong into the enemy lines.

This selfless act reinvigorated the Roman troops, who rallied behind Fabius Maximus and eventually broke the enemy coalition.

The victory at Sentinum was a decisive moment in the Third Samnite War and in Rome's rise to power.

The outcome of the battle allowed Rome to continue its expansion, eventually subduing the Samnites and securing control over the Italian Peninsula.

The Battle of Sentinum thus holds a significant place in Roman history, as it marked a pivotal step toward the establishment of the Roman Republic as the dominant power in the region, setting the stage for its eventual transformation into a vast empire.

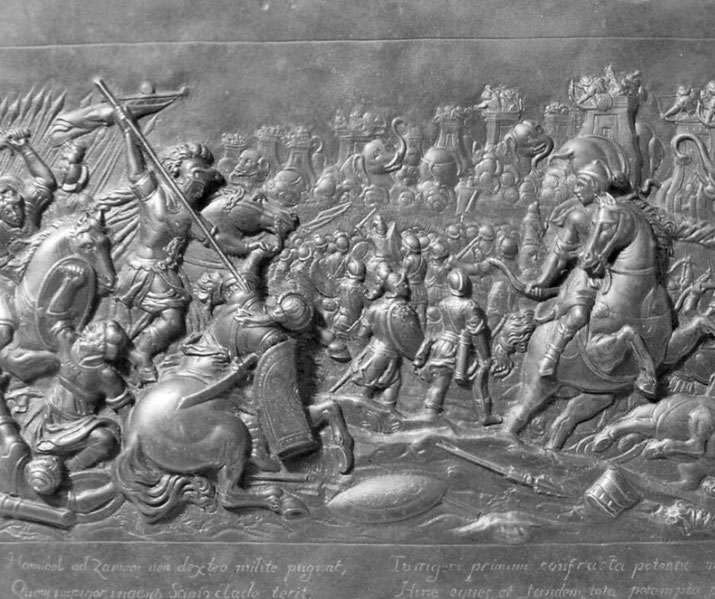

4. Battle of Cannae (216 BCE)

The Battle of Cannae, fought on August 2, 216 BCE, remains one of the most renowned and studied military engagements in history.

This epic confrontation took place during the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), a brutal struggle between the Roman Republic and the Carthaginian Empire, led by the brilliant and enigmatic general Hannibal Barca.

Cannae, a small village in southern Italy, became the setting for this legendary showdown.

The Roman army, commanded by consuls Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro, significantly outnumbered Hannibal's forces.

Yet, it was Hannibal's tactical genius that would ultimately decide the fate of the battle.

Employing a tactic that has since become synonymous with his name, Hannibal orchestrated a double envelopment of the Roman forces.

He positioned his infantry in a crescent formation, with the Carthaginian center gradually retreating as the Roman legions pressed forward.

As the Romans advanced, they unknowingly exposed their flanks to Hannibal's cavalry, which then executed a devastating pincer movement, encircling and trapping the Roman soldiers.

The outcome was nothing short of catastrophic for Rome. The Roman army suffered an estimated 50,000 to 70,000 casualties, while Carthaginian losses were considerably lower. Included in Rome's losses were 80 senators, which was nearly one-third of its members.

The scale of the defeat was unprecedented, and its psychological impact on Rome was immense.

However, despite the magnitude of Hannibal's victory, it did not lead to the collapse of the Roman Republic, which managed to regroup and ultimately prevail in the Second Punic War.

The Battle of Cannae remains a symbol of Hannibal's tactical brilliance and the prowess of his Carthaginian forces.

5. Battle of Zama (202 BCE)

The Battle of Zama, fought in 202 BCE near modern-day Tunisia, marked the dramatic climax of the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) and the conclusion of the epic struggle between Rome and Carthage.

The Roman Republic, led by the talented general Publius Cornelius Scipio, later known as Scipio Africanus, faced off against the Carthaginian forces commanded by the legendary Hannibal Barca.

While the exact location of the battlefield remains uncertain, its significance in the annals of history is indisputable.

After a series of victories in Italy, including Cannae, Hannibal was recalled to Africa to defend Carthage against Scipio's advancing forces.

Both armies consisted of infantry and cavalry, and Carthage also had fearsome war elephants.

Scipio's strategic brilliance was on full display at Zama, as he effectively neutralized Hannibal's elephants by employing a staggered formation of maniples, which allowed the charging beasts to pass through the gaps in the Roman lines without causing significant damage.

Additionally, Scipio's Numidian cavalry, led by King Masinissa, proved instrumental in countering and defeating the Carthaginian cavalry, before returning to the battlefield to attack Hannibal's infantry from the rear.

The defeat at Zama marked the end of Hannibal's military career and signaled the conclusion of the Second Punic War.

The victory solidified Rome's position as the dominant power in the Mediterranean and led to a peace treaty that imposed harsh terms on Carthage, including the loss of its territories, a crippling war indemnity, and the reduction of its military capabilities.

The Battle of Zama serves as a testament to Scipio Africanus's tactical genius and Rome's ability to adapt and learn from its past experiences.

Carthage would never fully recover, and Rome would eventually destroy the city during the Third Punic War in 146 BCE.

6. Battle of Pydna (168 BCE)

The Battle of Pydna, fought in 168 BCE, was a decisive engagement in the Third Macedonian War (171-168 BCE) between the Roman Republic and the Kingdom of Macedon.

This conflict signaled the climax of Rome's long struggle to assert control over the Hellenistic kingdoms of the Eastern Mediterranean.

The battle pitted the Roman legions, led by consul Lucius Aemilius Paullus, against the Macedonian phalanx commanded by King Perseus of Macedon, the son of the famous King Philip V.

The battle took place near the town of Pydna, in the region of Macedonia, present-day Northern Greece.

The Macedonian forces were composed primarily of the renowned phalanx, a tightly-packed formation of heavy infantry armed with long spears known as sarissas.

The Romans, on the other hand, deployed their legions in their customary manipular formation, which emphasized flexibility and maneuverability.

The battlefield featured uneven terrain that proved to be a decisive factor in the outcome of the battle.

As the Macedonian phalanx advanced, the rough ground disrupted its cohesion, creating gaps in the formation that the Roman legions were able to exploit with devastating effect.

The Romans achieved a resounding victory at Pydna, with the Macedonian army suffering heavy casualties and King Perseus being captured shortly after the battle.

The battle ended the Third Macedonian War and led to the subjugation of the Kingdom of Macedon.

Rome divided the Macedonian territory into four client republics, ending the Antigonid dynasty and effectively putting an end to the era of Hellenistic kings in Greece.

The Battle of Pydna not only demonstrated the superiority of Roman military tactics and organization but also cemented Rome's status as the dominant power in the Mediterranean.

It marked a significant step in the Roman Republic's expansion eastward and foreshadowed its eventual conquest of the entire Hellenistic world.

7. Battle of Pharsalus (48 BCE)

The Battle of Pharsalus, fought in 48 BCE in central Greece, was a critical engagement in the Roman Civil War between the forces of Julius Caesar and the senatorial faction led by Pompey the Great.

The battle not only marked a decisive turning point in the civil war but also had far-reaching implications for the Roman Republic, as it set the stage for the rise of Caesar and the eventual transition to the Roman Empire.

As tensions between Caesar and Pompey reached a boiling point, the two Roman generals and their respective armies faced off near the town of Pharsalus.

Despite being outnumbered over 2:1 in both infantry and cavalry, Caesar's tactical acumen and the battle-hardened experience of his legions would prove to be decisive.

He deployed his infantry in a compact formation, with a specially trained unit of infantrymen on the flanks to counter the threat of Pompey's superior cavalry.

As the battle commenced, Caesar's forces managed to hold the line against the senatorial army, and his infantry successfully repelled Pompey's cavalry charge.

Seizing the opportunity, Caesar launched a counterattack that shattered Pompey's center and ultimately routed his forces.

The defeat at Pharsalus forced Pompey to flee to Egypt, where he was ultimately assassinated.

The victory solidified Caesar's control over the Roman Republic, allowing him to consolidate his power and eventually become the undisputed ruler of Rome.

However, Caesar's triumph would be short-lived, as his increasing authority and the breakdown of the traditional republican institutions led to his assassination in 44 BCE.

The Battle of Pharsalus remains a seminal event in Roman history, symbolizing the culmination of a power struggle that would forever change the political landscape of Rome.

The battle served as a harbinger of the demise of the Roman Republic and the dawn of the Roman Empire, with the rise of Augustus, Caesar's adopted son, as its first emperor.

8. Battle of Actium (31 BCE)

The Battle of Actium, fought on September 2, 31 BCE, was a monumental naval engagement that marked the end of the Roman Republic and heralded the beginning of the Roman Empire.

The battle was the culmination of a long-standing rivalry between Octavian, the adopted son of Julius Caesar, and the combined forces of Mark Antony and his lover, the Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII.

The clash took place near the promontory of Actium, on the western coast of Greece, and would determine the fate of Rome and the Mediterranean world.

Octavian, who would later become Augustus, the first Roman emperor, commanded a formidable fleet under the able leadership of his admiral, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa.

Antony and Cleopatra's forces were comprised of a mixture of Roman and Egyptian ships.

Despite having a larger fleet, Antony's forces were disadvantaged by the size and maneuverability of their vessels compared to the smaller, swifter Roman warships commanded by Agrippa.

The battle was characterized by a series of tactical moves and counter-maneuvers, with Agrippa's forces gradually gaining the upper hand.

As the situation became increasingly dire for Antony and Cleopatra, they made the fateful decision to flee the battle with a portion of their fleet, hoping to escape to Egypt.

The remaining forces, demoralized by the departure of their leaders, were quickly defeated by Octavian's fleet. Over 200 ships were lost by Antony, with only 60 managing to escape to Egypt.

The Battle of Actium resulted in a decisive victory for Octavian, effectively sealing the fate of Antony and Cleopatra.

In the aftermath of the battle, Octavian pursued his adversaries to Egypt, where Antony and Cleopatra ultimately committed suicide in the face of imminent defeat.

With their demise, Octavian consolidated power, bringing the Roman Republic to an end and inaugurating the Roman Empire under his rule as Augustus.

The Battle of Actium thus holds a central place in Roman history, signifying the end of a tumultuous period of civil war and the birth of a new era of imperial stability and prosperity that would define the Pax Romana.

9. Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 CE)

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, which took place in 9 CE, was a turning point in Roman history and a devastating defeat that would haunt the collective memory of the Roman Empire for centuries.

The battle occurred in the dense forests of what is now modern-day Germany, where a coalition of Germanic tribes, led by the Cheruscan nobleman Arminius, ambushed and annihilated three Roman legions under the command of Publius Quinctilius Varus.

Arminius, who had served in the Roman army and was familiar with its tactics, used his knowledge and understanding of the terrain to lead the Roman forces into a carefully prepared trap.

As the legions marched through the narrow, winding passages of the Teutoburg Forest, they were beset by torrential rain and harsh conditions that greatly hindered their movement.

The Germanic tribesmen, taking advantage of the Romans' vulnerability, launched a series of devastating guerrilla attacks that gradually wore down the beleaguered legions.

Caught off guard and unable to form an effective defensive formation in the treacherous forest terrain, the Roman forces were systematically decimated.

The defeat was so complete that an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 Roman soldiers were killed, with the few survivors fleeing in disarray.

The loss of the three legions and the disgraceful capture of the legionary eagles dealt a severe blow to Rome's military prestige and struck fear into the hearts of its citizens.

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest marked the end of the focused attempt by Rome to conquer and assimilate the Germanic tribes east of the Rhine River, and it established the Rhine as the natural frontier between the Roman Empire and the Germanic lands.

The battle would be remembered as one of Rome's greatest military catastrophes, and its cautionary tale would serve as a stark reminder of the dangers of underestimating one's enemies and the importance of understanding the challenges posed by unfamiliar terrain.

10. Battle of Watling Street (61 CE)

The Battle of Watling Street, fought in 61 CE, was a pivotal and brutal engagement between the Roman Empire and the native Britons, led by the warrior queen Boudica of the Iceni tribe.

The battle took place along the Roman road of Watling Street, in what is now present-day England, and was the climax of a violent revolt that erupted in response to the Roman occupation of Britain and the mistreatment of the native population.

Boudica, incensed by the abuse her people suffered at the hands of the Romans, spearheaded a rebellion that brought together several British tribes in a united front against their oppressors.

The rebels enjoyed a series of initial successes, including the sacking of the Roman settlements at Camulodunum (modern-day Colchester), Londinium (London), and Verulamium (St. Albans).

These victories emboldened the Britons and swelled the ranks of Boudica's army, which is believed to have numbered in the tens of thousands.

However, despite their numerical superiority, the Britons would face a well-disciplined and battle-hardened Roman force led by the governor of Britain, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus.

He chose the site of the battle strategically, positioning his forces with their backs to a dense forest and narrowing the approach along Watling Street to prevent the Britons from utilizing their superior numbers.

As Boudica's forces charged, the Roman soldiers held their ground, eventually launching a devastating counterattack that broke the Britons' assault and led to a massive rout.

The Battle of Watling Street marked the end of Boudica's rebellion and solidified Roman control over Britain.

The scale of the defeat was catastrophic for the Britons, with some ancient sources claiming that as many as 80,000 rebels were killed during the battle, compared to only 400 Roman casualties.

The battle serves demonstrates the effectiveness of Roman military tactics and discipline, even against overwhelming odds.

Although Boudica's revolt was ultimately unsuccessful, her courage and determination in the face of foreign occupation have endured as a symbol of resistance.

11. Battle of Abritus (251 CE)

The Battle of Abritus, fought in 251 CE near the city of Abritus (located in modern-day Bulgaria), was a devastating defeat for the Roman Empire that marked a low point in its struggle against the barbarian invasions.

The battle took place during the crisis of the third century, a period of political instability, economic decline, and external threats that challenged the very existence of the Roman Empire.

In this particular engagement, Roman forces under the command of Emperor Decius faced off against an army of Gothic invaders led by the chieftain Cniva.

The Goths, who had crossed the Danube River into Roman territory, launched a series of raids and attacks on Roman settlements, causing considerable destruction and panic.

In response, Emperor Decius assembled an army to counter the Gothic threat and drive them out of Roman lands.

However, Decius's forces found themselves ill-prepared for the challenge posed by the Goths, who were well-versed in guerrilla warfare and adept at exploiting the weaknesses of their opponents.

As the Roman army pursued the Gothic forces into the marshy terrain near Abritus, they became bogged down and vulnerable to the hit-and-run tactics employed by the Goths.

The battle quickly turned into a disaster for the Romans, with their forces being outmaneuvered and suffering heavy casualties.

In the end, the Roman army was decisively defeated, and Emperor Decius, along with his son and co-emperor Herennius Etruscus, perished in the battle.

The Battle of Abritus was a significant blow to the Roman Empire, as it marked one of the first times a Roman emperor was killed in battle by a foreign enemy.

The loss further weakened the already fragile empire, as the crisis of the third century continued to escalate.

In the years that followed, the Roman Empire would undergo a series of reforms and military reorganizations in an attempt to address the challenges posed by the barbarian invasions and restore stability to the empire.

12. Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312 CE)

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge, fought on October 28, 312 CE, was a significant engagement in the history of the Roman Empire, as it not only determined the outcome of a civil war but also marked the beginning of the rise of Christianity within the empire.

The battle took place near the Milvian Bridge, which crossed the Tiber River in Rome, and pitted Constantine the Great's forces against those of his rival, Maxentius.

The battle was a result of the ongoing power struggle within the Roman Empire, as Constantine and Maxentius vied for control following the collapse of the Tetrarchy, a system of government in which four emperors ruled different regions of the empire.

Constantine, the Western Augustus, marched his army to Rome to confront Maxentius, who had declared himself the rightful ruler of the Western Roman Empire.

In the days leading up to the battle, Constantine is said to have experienced a vision of the Christian cross in the sky, accompanied by the words "In this sign, conquer."

Inspired by this divine intervention, Constantine had the Chi-Rho symbol, an early Christian symbol, painted on his soldiers' shields.

Maxentius, feeling confident in his position, chose to meet Constantine's forces at the Milvian Bridge.

As the battle unfolded, the Roman soldiers bearing the Christian symbol fought fiercely, and Constantine's tactical prowess was on full display.

Maxentius's forces were pushed back towards the Tiber River, with many drowning as they attempted to retreat across the river.

Maxentius himself met a similar fate, as he drowned when the temporary bridge he had constructed collapsed under the weight of his retreating army.

The victory at the Milvian Bridge solidified Constantine's position as the undisputed ruler of the Western Roman Empire, and he would later become the sole emperor of the entire Roman Empire.

The battle's significance extends beyond its immediate political ramifications, as Constantine's adoption of Christianity as his patron religion paved the way for its rapid growth and eventual establishment as the official religion of the Roman Empire.

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge thus represents a critical turning point in both Roman and Christian history, marking the beginning of a new era in which the two would become inextricably linked.

13. Battle of Adrianople (378 CE)

The Battle of Adrianople, fought on August 9, 378 CE, was a catastrophic defeat for the Roman Empire and a watershed moment in the decline of its military power.

The battle took place near the city of Adrianople (modern-day Edirne, Turkey) and saw the forces of the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens face off against an army of Gothic rebels, led by the chieftain Fritigern.

The Goths, originally from Scandinavia, had sought refuge within the Roman Empire due to the pressure from the Huns.

However, they were mistreated and marginalized by the Roman authorities, which eventually led to their uprising.

The Gothic forces, bolstered by their alliance with other barbarian tribes, posed a significant challenge to the Roman Empire's eastern frontier.

In response, Emperor Valens assembled an army to suppress the rebellion and reassert Roman dominance.

Eager to claim victory before the arrival of reinforcements from the Western Roman Emperor Gratian, Valens rushed into battle against the Gothic forces.

The Roman army, composed mainly of infantry, was ill-prepared to face the Gothic army which had significant heavy cavalry forces as well as infantry.

As the battle raged, the Romans were unable to withstand the ferocious onslaught of the Gothic cavalry, and their lines began to collapse.

The defeat was devastating for the Romans, with the majority of the army being killed, including Emperor Valens himself. Some sources day 20,000 out of 30,000 troops perished.

The Battle of Adrianople marked a turning point in the fortunes of the Roman Empire.

The heavy losses exposed Rome's military vulnerability and emboldened other barbarian tribes to challenge Rome's authority.

The battle also signaled a shift in the balance of power between infantry and cavalry on the battlefield, with the latter proving to be a decisive force in the conflict.

In the years following Adrianople, the Roman Empire would continue to grapple with internal strife and external threats, ultimately leading to its decline and eventual fall.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.