The cruel abduction of Persephone: How the ancient Greeks explained the four seasons

The ancient Greeks told stories about the gods and goddesses to explain the natural processes they saw around them.

A notable example is the tale of Persephone. This myth focuses on Persephone’s trip to the Underworld and the change of seasons on Earth.

In doing so, it shows human life as a story of loss, longing, and the cycle of new growth.

Who is Persephone?

Persephone was the daughter of Zeus, the king of the gods, and Demeter, who were both siblings and children of the Titans, Cronus and Rhea.

Zeus was the leader of the gods and held the highest authority in the divine world, while Demeter controlled farming and the fertility of the earth: areas essential for people’s survival.

Their daughter, Persephone, was described as very beautiful and who captured the hearts of mortals and gods.

Greek poets and storytellers portrayed her as a goddess who represented the freshness and appeal of spring.

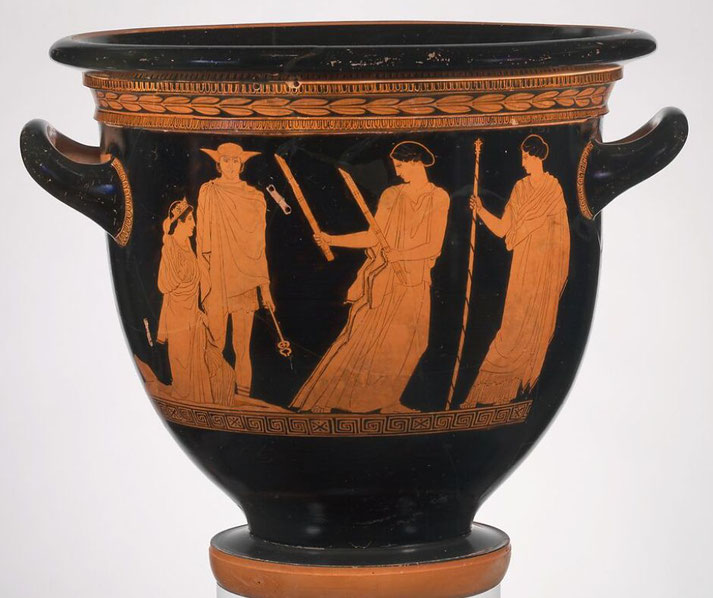

In a way, her charm matched the life of the natural world. Often in art and writing, artists and authors showed her as young, graceful, and bright, surrounded by symbols of spring and fertility, such as flowers and ripe fruits.

Why she was abducted by Hades

The Homeric Hymn to Demeter, written around the seventh century BCE, provides the earliest detailed account of her abduction, in which Hades was impressed by her beauty and grace.

He asked Zeus for permission to take her as his wife, and the king of the gods agreed because he considered it a way to restore the balance of power among the gods.

Then Hades captured Persephone as she picked flowers and took her to his dark kingdom, far from the sunlight and life of the world above.

Because of this act, Demeter became very sad, causing the once fertile earth to turn cold and lifeless, as she held back her gifts from it.

In turn, crops failed and famine threatened people’s lives. The other gods and humans soon saw how serious the situation was.

In Greek thought, natural events were explained when a god’s emotional state affected the condition of Earth, as they believed their actions and feelings had real effects on human life.

The plan to rescue Persephone

The problem on Earth led Zeus to act, and recognising that balance needed to return, he sent Hermes, the messenger god, to negotiate her return.

The story changed when people found that she had eaten pomegranate seeds in the Underworld, where the rule was that anyone who ate or drank anything there could not leave.

By eating the pomegranate seeds, she tied her fate to that realm, and as a result, she could not fully return to the living world.

Demeter, her mother, was very upset when she discovered what had happened and an agreement followed where the young goddess would spend part of the year with her mother and the rest with Hades.

This arrangement created the seasons: when she was with Demeter, Earth experienced spring and summer because her mother felt joy.

When she returned to Hades, Demeter grieved and the world experienced autumn and winter, times of rest when life seemed to fade.

The cycle of the seasons reminded people of the story of the gods and explained the natural pattern in a human-focused way.

How the Greeks celebrated this story every year

The ancient Greeks’ cultural and religious practices were closely linked to their mythology, and this was clear in how they honoured gods like Demeter and Persephone.

For example, central to these practices were various festivals and ceremonies that celebrated the gods and the natural events they symbolised.

In particular, one of the most important religious events was the Eleusinian Mysteries, which were held in honour of Demeter and Persephone.

Specifically, these ceremonies were held every year at Eleusis, near Athens. Their details remained hidden from non-initiates.

The Greater Mysteries took place in the autumn and showed Persephone going down to the Underworld.

The Lesser Mysteries took place in the spring and celebrated her return to the surface and her reunion with Demeter.

In addition, taking part in these mysteries was considered a very holy and life-changing experience.

It offered hope of a better fate after death and a deeper spiritual understanding.

Outside of the Eleusinian Mysteries, other festivals also had a key place in the religious calendar.

The Thesmophoria was a festival only for women. It was held over several days and celebrated fertility and Demeter's gifts to people, such as farming and the rules for family and marriage.

Women who took part in rituals were involved in fasting, processions and sacrifices, all which showed the themes of life, death and rebirth that were central to Demeter’s story.

Temples dedicated to Demeter and Persephone were also important and were often located in areas crucial for farming.

At these temples, people brought offerings, usually crops or animals, asking the gods for a good harvest or protection from natural disasters.

The profound meaning behind the myth of Persephone

Persephone’s going down to and coming back from the Underworld is seen as a symbolic story for planting seeds and their later growth into crops.

This view shows the Greeks’ close connection to the land and their reliance on farming to live.

In the same way, it shows the unavoidable change from youth to adulthood, and then to death and the hope of rebirth or renewal.

Moreover, Persephone’s two roles as the goddess of spring and the queen of the Underworld show these two sides of life.

Additionally, her story shows the Greek understanding of the afterlife and the idea of everlasting life for the soul, a belief later adopted and modified by different philosophical schools in ancient Greece.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.