Pyramid Texts of ancient Egypt: The oldest funerary spells explained

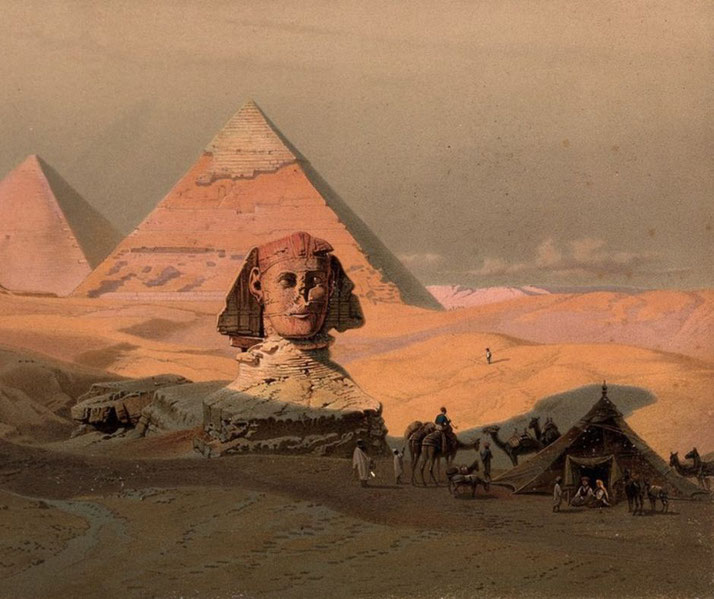

Many people are fascinated by the mysteries of the ancient Egyptian pyramids and millions of tourists visit them every year.

Perhaps the most incredible part of these structures are the inscriptions carved into the deepest part of them: sacred texts that were never meant to be seen by the living.

As a result, the so-called ‘Pyramid Texts' hide some of the most profound information about what the ancient believed about the gods, the pharaohs, and the true nature of the afterlife.

What are the Pyramid Texts?

The Pyramid Texts are the earliest known ancient Egyptian religious writing, dating all the way back to the late Old Kingdom period, around 2400–2300 BBCE.

As such, they are the oldest surviving funerary literature in Egypt and, also, some of the oldest religious writings in the entire world.

The first known version is on the pyramid of King Unas from the 5th Dynasty (c. 24th century BCE) at Saqqara, but they can be found across a series of key pyramids, created by the following royal figures (all at Saqqara):

| Owner of the pyramid text | Approximate date |

| Unas | Dynasty V (c. 2353–2323 BCE) |

| Teti | Dynasty VI (c. 2323–2291 BCE) |

| Pepi I | Dynasty VI (c. 2289–2255 BCE) |

| Merenre I | Dynasty VI (c. 2255–2246 BCE) |

| Pepi II | Dynasty VI (c. 2246–2152 BCE) |

| Queen Neith | Dynasty VI, wife of Pepi II |

| Queen Iput II | Dynasty VI, wife of Pepi II |

| Queen Wedjebetni | Dynasty VI, wife of Pepi II |

| Queen Behenu | Dynasty VI, probable wife of Pepi II |

| Qakare Ibi | Dynasty VIII (c. 2109–2107 BCE) |

Each one of these pyramids has different sections of the Pyramid Texts, carved on the inner walls of corridors, antechambers, and/or sarcophagus chambers.

The primary purpose of the Pyramid Texts was to ensure the king’s survival in the afterlife.

In essence, they were a toolkit of magical spells that were intended to protect the deceased pharaoh’s physical body, while guiding his spirit, and ultimately transforming him into an akh: a transfigured spirit who could live eternally with the gods.

Many of the spells were meant to be recited by priests during the funeral rites during the burial process, as well as being spoken by the king’s soul itself after death.

In practical terms, these texts served two main functions. Firstly, it guarded the tomb through a series of apotropaic spells which warded off serpents, demons, or any harm to the king’s corpse.

Secondly, there were provisioning utterances, which mystically provided the king with food, drink, and essential religious offerings in the next world.

For example, some incantations reanimate the mummy by addressing the king’s body parts directly, such as helping him to sit up and breathe again, so that his soul may separate from the corpse.

Others “open the way” for the king to climb into the heavens by describing celestial boat ferries, ladders, or even the wind as a way for the pharaoh to travel upward.

What do the Pyramid Texts say?

When read together, the Pyramid Texts consist of hundreds of hieroglyphic inscriptions that are organized in discrete passages often called ‘utterances’ or ‘spells’.

Many spells invoke a wide range of Egyptian deities. In fact, over 200 gods and goddesses are mentioned by name, from great gods like Ra, Osiris, Isis, and Thoth to lesser local deities.

Interestingly, the earliest reference to the god Osiris is in the Pyramid Texts.

Rather than telling full myths, the inscriptions allude to famous mythological events and symbols indirectly, as if the reader was already expected to know what was being mentioned.

For example, they reference the Contendings of Horus and Set and the voyage of the sun god Ra.

The texts often take the form of speeches or commands directed at supernatural beings.

For instance, the king might address the gods, declare his own transformation, or demand entry into the sky. One notable passage is the so-called ‘Cannibal Hymn’ (Utterances 273–274) from Unas’ pyramid, which describes the king hunting down and eating the gods to absorb their powers.

As an interesting aside, the king is identified with various gods throughout the texts.

In one place he is called the son of Ra, or Osiris, and he soars into the sky as a falcon or star, like Horus.

However, the language is poetic: the king climbs ramps, flies on wings, or ascends on a ladder to reach the heavens.

Meanwhile other texts are more ritualistic and are primarily dialogues or ceremonies, such as offering rituals, performed by priests during the burial service.

An example: Utterance 226 of Unas’ Pyramid

“Wrapped up is a twisted-snake by another twisted-snake, [and the] toothless calf which came from the pasture has been wrapped up.

Earth, swallow up what has come from you!

Monster, lie down! Crawl away!

The Majesty of the Pelican has fallen in the water.

Snake, turn over, that Ra may see you!”

In this particular incantation, the speaker, who would be the king or a priest on his behalf, addresses a dangerous serpent directly.

It describes one snake being overpowered by another, and a young animal (a “toothless calf”, that is probably a young hippopotamus) is caught in the tussle.

The spell then commands the snake to be swallowed by the earth, lie down and glide away, and turn over so that the sun-god can see and destroy it.

This kind of spell was intended to magically subdue any snake that might enter the tomb.

In ancient Egypt, snakes were a common symbol of chaos and danger, both on earth and in the underworld and, by inscribing this spell in the pyramid, the Egyptians hoped that a snake or the chaos it represented could not attack the king’s body or spirit.

The curious nature of the Pyramid Texts

The inscriptions themselves were often arranged in vertical columns separated by ruling lines.

They were typically left unillustrated and were originally enhanced with color. In King Unas’ tomb, for instance, the hieroglyphs were incised in sunk relief and filled with blue pigment, traces of which still remain on the stone.

Above them, the ceiling of Unas’ burial chamber was painted with golden stars on a black background, which was intended to mimic the night sky.

This created the effect that the texts were spoken under the eternal stars. Each column of text is read from bottom to top, as if the spells are lifting the king upward.

Often the spells nearest the sarcophagus relate to protecting the body or calling the king to rise.

The placement of spells was often done with particular attention to their physical position.

Scholars have noticed that certain walls were dedicated to specific themes. For example, east wall spells relate to the sunrise and rebirth, while west wall relate to the realm of the dead.

In total, the known Pyramid Texts totals around 759 inscriptions in the standard compilation.

In fact, the consistency of the various inscriptions across multiple pyramids actually suggests a canon of funerary texts was in circulation among priestly scribes by the end of the Old Kingdom.

How are they different from the Coffin Texts?

In the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2055–1650 BCE), the use of Pyramid Texts inside royal pyramids had ceased and the pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom did not inscribe texts on their tomb walls.

However, many of the same spells and concepts were adapted into the so-called ‘Coffin Texts’.

These were a new collection of funerary spells that were written on the wooden coffins of non-royal elites during the First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom.

Essentially, this meant that the rituals and incantations once reserved for kings became accessible to nobles and commoners who could now afford a decorated coffin.

As a result, a large portion of Coffin Text spells were directly derived from the earlier Pyramid Texts.

For example, we find versions of the Unas spells on Middle Kingdom coffins, such as the Cannibal Hymn when it reappears as Coffin Text Spell 573.

Alongside these, many new spells were composed, often with a greater emphasis on the god Osiris and the concept of judgment after death.

Then, in the New Kingdom period (ca. 1550–1070 BCE), the tradition evolved further into the famous Book of the Dead, which was more accurately known to the Egyptians as the ‘Book of Coming Forth by Day’.

The Book of the Dead was, in reality, a spiritual successor to the Coffin Texts as it compiled many Coffin Text spells and, by extension, Pyramid Text spells, into a standardized, illustrated funerary papyrus scroll for use in tombs.

In other words, the Pyramid Texts are the foundational layer of a tradition that leads directly to the Book of the Dead.

Numerous chapters of the Book of the Dead have antecedents in Pyramid Text utterances, though often evolved in form and language of later Egyptian dialects.

Often, they also featured new emphases like negative confessions and the heart weighing.

The underlying goal, however, remained consistent: to provide the deceased with knowledge and power to achieve eternal life.

Even during the New Kingdom, some Pyramid Texts were still carved on tomb walls of officials, especially in Saqqara.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.