What the Titanic's passengers ate: How menus varied dramatically based upon social class

Billed as the most luxurious ship of its time, the Titanic promised its passengers an unmatched experience as they journey across the Atlantic on their way to New York.

However, the experience onboard varied dramatically based each person's social standing in Edwardian society. As a result, first-class passengers dined in opulence, with menus crafted by world-class chefs, while those in third class shared basic, hearty meals designed to simply sustain them on their voyage.

But just how wide this gap was is quite shocking to us, over 100 years later.

First-class dining: Luxury at sea

Guests who paid the highest fares on the Titanic entered an elaborate dining room, adorned with intricate woodwork and gleaming chandeliers.

The most expensive first-class ticket on the Titanic cost £870, which is equivalent to around $100,000 today.

Men and women dressed in their finest attire, adhering to the Edwardian standards of fashion and manners.

White-gloved stewards who were impeccably trained moved silently between tables, presenting elaborate courses to the wealthiest passengers.

The dining room's atmosphere was refined, with soft music played by the ship’s orchestra, which created a tranquil setting for conversations between prominent figures like John Jacob Astor and Benjamin Guggenheim.

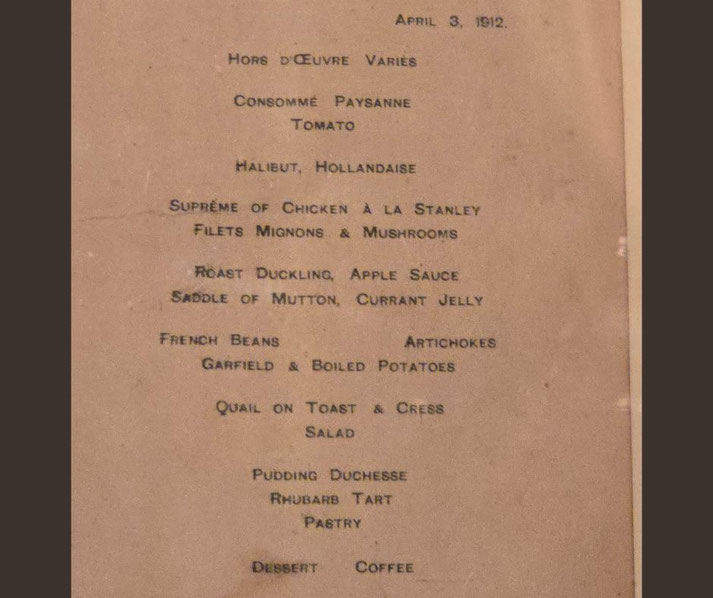

The menus served to first-class passengers were designed to be the height of culinary sophistication.

Dishes such as oysters, filet mignon, and roast duckling were followed by decadent desserts like pudding duchesse and éclairs.

Simply put, the meals were meant to mirror the opulence these passengers were accustomed to on land.

As was fashionable at the time, French cuisine dominated the selection, with every detail—from the sauces to the wine pairings—carefully chosen to elevate the dining experience.

First-class passengers like Lady Duff Gordon and Isidor Straus, who were well known in their social circles, would have selected their meals from menus that read like a guide to haute cuisine.

For many, dining in first class was about being seen among the elite of the travellers.

The social atmosphere created an informal competition, where status was reaffirmed through conversations and the presentation of one’s wealth.

Edwardians like Countess of Rothes and millionaire Charles Hays, who sat among fellow aristocrats and industrialists, enjoyed meals served on fine china and sterling silver.

Every bite was a reminder of the vast divide between those who could afford to live in luxury and the rest of the world, including those below deck.

Second-class dining: A taste of comfort

In comparison, second-class dining aboard the Titanic offered passengers a comfortable experience, though it lacked the extravagance of the first-class meals.

The second-class dining room, which was modestly decorated, seated passengers who were mostly professionals, teachers, and middle-class families.

Unlike first-class diners who indulged in lavish courses, second-class passengers ate meals that were simpler but comforting, focusing more on practicality than luxury.

The meals were well-prepared, but they catered to a more traditional palate, leaving behind the French influences seen in the first-class menu.

These passengers enjoyed dishes like roast turkey, curried chicken, and plum pudding, with portions that were generous and satisfying.

There was an emphasis on hearty meals, which reflected the fact that many second-class passengers were used to simpler home-cooked fare.

Breakfasts often included porridge, ham and eggs, and fresh bread, which gave passengers a sense of familiarity and comfort.

While there were fewer courses than in first class, the meals remained well-rounded and nourishing.

The dining environment in second class was welcoming and far more informal than in first class.

Passengers sat at communal tables, which meant that dining became a social affair where conversations flowed easily.

The absence of strict dining protocols created a more relaxed atmosphere, though there remained a sense of structure and civility.

Service was prompt and efficient, which allowed passengers to enjoy their meals without the elaborate rituals seen in the upper-class dining rooms.

For many second-class passengers, this combination of good food and a pleasant environment provided a taste of comfort during their journey.

Third-class dining: Simplicity and sustenance

Third-class passengers, numbering around 700, were largely European immigrants from countries such as Ireland, Sweden and Italy, seeking a new life in America.

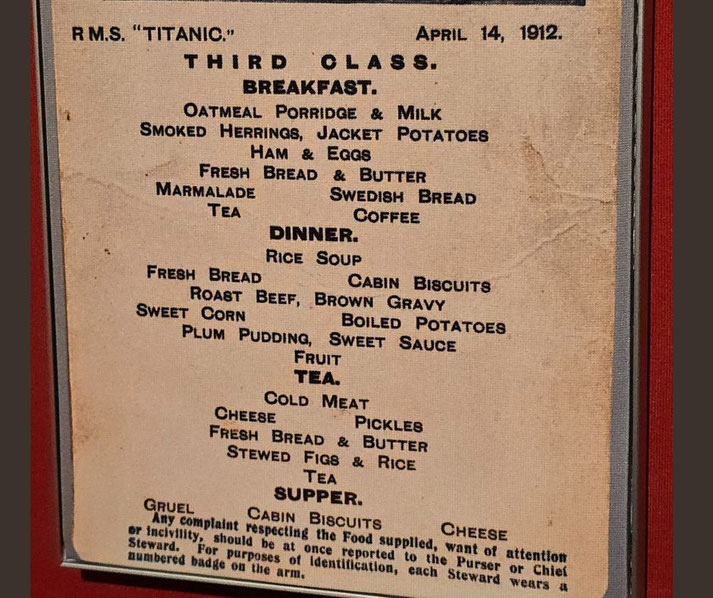

Their meals were designed to be basic and filling, providing enough sustenance for the long voyage.

Breakfasts typically consisted of oatmeal, milk, and biscuits, while lunches and dinners featured basic but hearty options like boiled beef, potatoes, and bread.

The food, even though it was plain, was fresh and sufficient to keep the passengers nourished throughout their journey.

While first- and second-class passengers enjoyed a variety of courses and delicacies, the steerage passengers received more standardized portions of staple foods.

These meals did not include the rich sauces or elaborate presentations seen in the other dining rooms, but the essentials were provided.

The variety was limited, and desserts were simple, often consisting of stewed prunes or rice pudding.

The menu was more focused on practicality and sustainability, ensuring that even with fewer resources, passengers could eat enough to remain healthy.

Perhaps most importantly, communal dining played a central role in the third-class experience, with passengers gathering in large, shared dining spaces.

These areas lacked the polished elegance of first-class or the modest comfort of second-class, but they were functional.

Around 300 people could be seated at once, creating a busy and often lively atmosphere.

Meals were served at set times, and passengers ate together at long tables, which allowed for conversation and a sense of camaraderie among travelers from different backgrounds.

Did they cater for special dietary considerations?

While the Titanic’s diverse passenger list included people from different countries and backgrounds, there was no widespread effort to provide meals specific to certain cultural tastes.

Italian and Eastern European immigrants who made up a large part of the third-class population would have eaten the standard fare provided to all in steerage.

However, some wealthier passengers, particularly in first class, who preferred specific European cuisines, could make requests for certain dishes or ingredients, thanks to the flexible service offered in their dining room.

That being said, accommodation for passengers with specific dietary restrictions was limited but present on the Titanic, particularly for those with religious needs.

Jewish passengers who were part of the large immigrant population in third class were offered kosher meals.

They were prepared in accordance with Jewish dietary laws, which meant that separate utensils and cooking facilities were used to prevent the mixing of meat and dairy.

While the options were more basic than what other passengers received, providing kosher meals showed an effort to cater to the religious needs of a significant group.

However, passengers who required specific foods due to medical conditions, such as those who were diabetic or who had digestive issues, would have had to make special requests.

Wealthier passengers in first class could rely on the kitchen staff to make adjustments to their meals.

However, for most passengers, especially those in third class, such accommodations were rare.

What did the crew eat on the Titanic?

The crew aboard the Titanic, like the passengers, ate meals that reflected their role on the ship and the class system.

The ship's crew consisted of 899 individuals, ranging from officers and engineers to stewards and stokers.

The officers, who held higher positions, enjoyed meals in their own dining room, and were served food that was substantial and varied.

They ate hearty dishes like roast meats, potatoes, and vegetables, which gave them the energy required for their demanding work schedules.

For the general crew, who worked long, physically exhausting shifts, especially in the boiler rooms, they needed filling food to maintain their strength.

Their meals often included staples such as boiled beef, soup, bread, and porridge.

This kind of food was enough to keep them energized for the difficult tasks they faced every day.

Breakfasts usually featured items like oatmeal and tea, providing a simple but effective start to their long workdays.

The kitchen staff prepared meals for the crew in a separate galley, which helped to ensure that their food was cooked efficiently to serve such a large number of workers.

The crew’s meals were served in a communal mess hall, with little time for leisurely eating.

Crew members who ate together quickly returned to their duties, knowing that the ship relied on their constant attention.

How much food was on the Titanic?

The Titanic carried over 75,000 pounds of fresh meat, 40,000 eggs, and 1,500 gallons of milk, among countless other items.

This vast quantity of provisions was stored in various compartments throughout the ship, including large, refrigerated areas to keep perishable goods fresh.

These spaces were located below deck, where cool temperatures helped preserve meats, dairy, and fresh produce.

Dry goods, such as flour and sugar, were stored in separate areas. Managing these supplies required careful planning, as chefs needed to ensure there was no waste while meeting the demands of three different classes of passengers.

The role of chefs and kitchen staff on the Titanic was crucial to maintaining the high standards expected by first-class passengers.

The kitchen staff, which numbered over 60 people, served the 324 first-class diners, 284 second-class passengers, and 709 in third class.

Preparing meals on such a large scale was a logistical challenge. The kitchen staff had to use multiple galleys, or kitchens, located on different decks to serve each class.

These galleys were equipped with modern equipment for the time, including electric toasters and mechanical potato peelers.

This complex system allowed the Titanic to provide a variety of meals to its passengers, despite the ship being a floating city in the middle of the Atlantic.

The last meal on the Titanic

On the evening of April 14, 1912, passengers aboard the Titanic sat down for what would be their final meal.

In the first-class dining room, the last supper consisted of an elaborate 10-course meal.

Oysters, consommé Olga, and filet mignon were among the dishes served. Wine flowed freely, and the air buzzed with conversations about business, travel, and the excitement of the journey.

The service continued into the night, with some passengers retiring to the smoking room or their suites.

In second class, passengers were served roast turkey with cranberry sauce, green peas, and boiled potatoes, which were followed by plum pudding and American ice cream.

As they finished their desserts and tea, many second-class passengers moved to the library or promenade deck, unaware that their last meal was one of peace before the chaos that would engulf the ship hours later.

For the third-class passengers, many of whom had eaten in the early evening, they received hearty meals such as roast beef, boiled potatoes, and bread.

After dinner, they gathered in common areas or returned to their bunks. As the ship struck the iceberg later that night, these passengers—along with those from the upper decks—were thrown into a nightmare that no meal could prepare them for.

That night, as the Titanic's passengers left the dining rooms, the plates and silverware were left behind, never to be used again.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.